In an art world currently filled with frivolous lightweight pieces (a little like the House of Commons) it is a pleasant change to find a show in a provincial gallery to rival that in any of the so-called ‘major’ art centres in the big cities. The Towner has worked with the National Gallery of Wales to bring to England a show, almost a retrospective, by artist David Nash. Although able to claim to be a local boy because he has a place in Lewes, Nash has literally carved out an artistic living in Blaenau Ffestiniog amongst the mountains of waste from the sadly defunct Welsh slate quarrying industry. Carved by Welsh carver Frank Triggs in oak, part of the Welsh art collection at the Celtic Manor

Carved by Welsh carver Frank Triggs in oak, part of the Welsh art collection at the Celtic Manor

When working as one of the design team building Wales’s first 5Star hotel, the Celtic Manor in Newport, we wanted to use Welsh slate to top the small table units installed in the corridors. To my horror I found most current Welsh quarries seemed to be owned by a road contractor and only produced slate to be pulverised for road surfacing. Similarly, the carved Welsh dragons curled around columns we commissioned for reception (one of which has its foot on an English shield) were intended to be in Welsh oak, but the oak came from France as Welsh oaks were apparently too small to make the large beasts. It is no surprise than to see that most of the range of woods used by David Nash have been sourced worldwide, and his ‘quarrying’ of logs has taken him to work all over the world.

His start was deliberate, thoughtful as is much of his work. His base is the old chapel in Blaenau Ffestiniog, Capel Rhiw. Although schooled in Brighton and at English art colleges, Nash has family roots reaching into Wales. Having made a total commitment to his art, he recognised the need for a sound economic base so bought cottages in Wales soon selling them to buy the a former Methodist chapel in Blaenau, Capel Rhiw, Here, free from the influences of the London art world, working as a woodsman, he immersed himself in the landscape and woodland of the Ffestiniog valley and its mountains of slate.

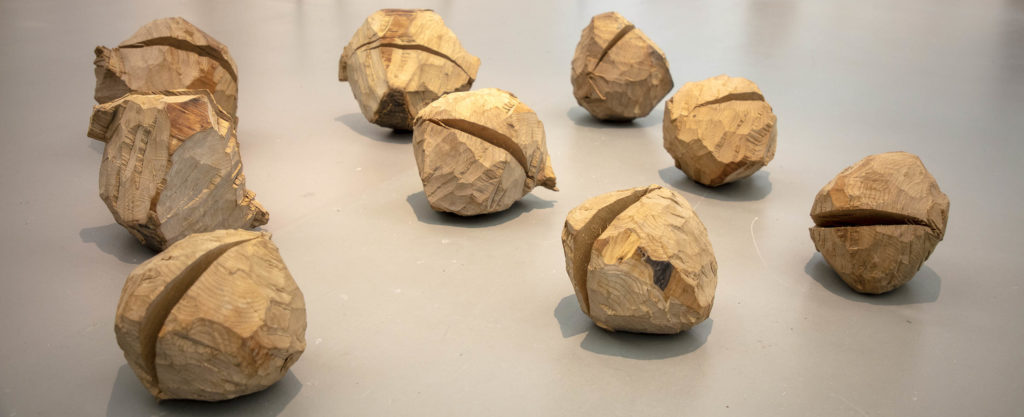

The show records ‘200 Seasons at Capel Rhiw’, effectively a major retrospective of his work. It starts with his first experience when he attacked a ‘tree quarry’ with an axe roughly carving off 9 spheres. These he stored in his new studio in the chapel, eventually becoming hidden behind sheets of hardboard and other materials as he worked to convert the chapel into a living and workspace, and acquiring a collection of different axes. Removing the boards some time later he discovered the spheres had split as the wood dried out , and although I think there may have been some gentle assistance to get the remarkably even level of splitting revealed, this first completed piece was to be echoed and reprised at different scales in the years ahead as he played with the wood and his tools.

Acquiring the responsibility to restore a vandalised piece of woodland a few miles from the chapel, Nash worked in harmony with the environment. His father bought the woodland at Coen-y-Coed and there Nash continued to engage with the natural environment and his loving reverence for trees, bringing trunks into the studio to ‘quarry’ and creating the circle of ash trees known as the ‘Ash Dome’. Created in 1972 this famous example of ‘Land Art’ has begun to suffer ash die back and recently three generations of the Nash family worked under David Nash’ guidance to plant a circle of 22 oaks around the slowly dying ash trees as a memorial replacement. The show has drawings and video records of the piece, and the videos in the show are hypnotic.  Video of Wooden Boulder

Video of Wooden Boulder

Almost the most hypnotic, and certainly for many watchers an emotive piece is the video of the Wooden Boulder Journey. The video is a romantic tale of how a large axe-carved wooden boulder took on a life of its own. Starting as it was rolled into a stream the film follows its journey, filmed and followed over years from stream to river, from river to estuary from 1978 until it was finally lost at sea in 2018. For the audience the oak ‘boulder’ took on a life of its own and the raindrop sequence at the end was seemingly intended to reflect a sad sense of loss after it vanished – maybe to be seen again one day on the Welsh coast, its current location unknown. It has disappeared before for years at a time and been relocated, blackened and reshaped by the action of time and weather, water and the earth.

As well as his axed pieces there are experiments with cutting unseasoned timber, watching the behaviour of the wood as its moisture dried out, shrinking and deforming. There are games played with charring with fire and blow torch, the charcoal finish rubbed with linseed oil to create seductive surfaces, the charcoal when unfixed being rubbed on paper to make its own image. There is a profound playfulness at work here, a freedom of exploration that delights the eye. Sadly, some of the pieces are unstable so they cannot be touched but one wants to stroke and caress the timber, to smell its scent so totally tactile are the pieces.

Amongst the wooden pieces stand a pair of enigmatic circles. One of these circles is made up of the seeds of native bluebells. They stand as a record of the planting of a large circle of bluebells on a hillside. In the spring a 39metre diameter blue circle appeared, visible from a distance on the hillside. Rising and falling with the seasons the piece lasted four years before the spread of the plants caused the loss of definition. Many of the images play with the seasonality of installations, seeing the changing nature of weather, the growth of moss and bluebells against the geometrics of man made structures. The thread is a fascination with the passage of time as an element in the works.

The show covers two floors of the spaces at the Towner and shows exuberantly how effective the remodelling of the galleries under new Director Joe Hill has been, enabling and enhancing the drama of these large pieces of sculpture. The works detail an intricate story of travel from working with an axe on a fallen oak, to residencies in Japan exploiting their trees: from working with power saws with foresters in Wales to expeditions to the US. The works reflect too, their own travels. Pieces like Big Bowl made from Mizunara (water oak) show the marks of being exhibited in earthquakes in Japan. Nash describes it as, now fully repaired, taking its place in the “congregation” of his works at Capel Rhiw.

Nash is of the same generation as I, passing through different art college just a year ahead in the 1960’s. His influences are of the period – Caro, Brancusi, Richard Long, Judd, painters Blake, Rothko and Rauschenberg amongst them – the 20th Century masters whose concern for materials and the elemental nature of art were and remain powerfully influential. His sculpture and drawings contain refences to the cone, the sphere and the cube, so influential in the Bauhaus and echoed with Cezanne and other 19th century masters. They reoccur throughout his work and show again the influence of ideas stemming as many ideas do from the collective memory, the mists of folk art and classicism: the triangle a property of fire, the circle representing eternal light and the divine, the square the immovable property of the external world. The 3d cone, sphere and cube were burned then rubbed on the paper to make teh images, before being sealed with linseed oil. The images were enhanced by drawing in with charcoal

The 3d cone, sphere and cube were burned then rubbed on the paper to make teh images, before being sealed with linseed oil. The images were enhanced by drawing in with charcoal

This influence from art college in the sixties also surfaces in references to Jarry’s play Ubu Roi, loosely based on Shakespeare’s ‘Macbeth’. I recently entitled one of my own paintings ‘Ubu’s Washing line’ and was amused that the Nash ‘Two Ubu’s’ echoed Jarry’s figures as did the hanging clothes in my own paint – reassured to find there was someone else out there familiar with Jarry’s work! So few understood the reference to Ubu that I retitled the piece ’Bunny’s Washing Line’. Two Ubus

Two Ubus

There is so much complexity and sensitivity in Nash’s work. The work builds on a relationship with the land, with Ffestiniog, and is rooted deeply in the past as well as reflecting an individual delight in materials and the workings of the natural environment. Nash is claimed as a minimalist in some writing. For others he belongs in the school of ‘Land Artists’. For me he has the mysticism characteristic of the Welsh, but above all he is an environmentalist, and in that sense very much a part of our future.

This show is a stunning exploration of one man, his work and his thinking. I doubt you will see a better sculpture show in 2019. At the Towner until 2nd February 2020, it has the bonus of being free, and the Towner café sells the best almond croissants to be had. Treat yourself. There is a book produced in collaboration with the sponsoring galleries too. I have already been four times, and will be going again soon, no doubt. Unmissable.

Recent Comments