“Knowing that life is so strange and so uncontrollable, there is no way, and art is impossible, as impossible as living. And yet one lives, and strange things happen, and art also happens, like falling in love.”

Alan Davie from the 1958 Wakefield Exhibition Catalogue

This show comes from the Hepworth Gallery in Wakefield. The gallery originated this show, but its roots go back much further in time. The original gallery was a local authority gallery supported by local industrialists from its opening in 1934. It quickly established its reputation by supporting artists like Moore and the eponymous Barbara Hepworth it is now named after. Renamed Hepworth in honour of the large gift of works from Hepworth’s daughters that spurred the development of the new building, its reputation lies not in its brick and mortar but in the forward thinking of its curators.

Davie and Hockney owe much to Helen Kapp, and this exhibition, transferred from the Hepworth in succession to the Towners previous blockbuster David Nash show, sits well in the new 2nd floor Galleries. The show traces parallel paths of these two English painters, one whose star still shines brightly whilst the other died almost unremarked in 2014, but whose work influenced the star. That work of Davie first received its major showing in the Wakefield Gallery in 1958, transferring to the Whitechapel where the predictable London literati credited it with the innovative reveal of Alan Davie’s work.

The vision that brought Davie to the public was the vision of curator Helen Kapp, given full credit in the exhibition and its lovely catalogue by the current Hepworth Curator of this show, Eleanor Clayton. Not only did Helen Kapp have the vision to buy Alan Davie’s works and mount the first major showing of them after his return from the USA, but she also bought one of my works in the mid 1970’s for the Arts Council collections. Much as Davie sank in obscurity in later life so my painting has vanished from history lost by the inept guardians of British art at the Arts Council. Flight into Italy – Swiss Landscape 1962 David Hockney Oil on Canvas 72 x 72 inches

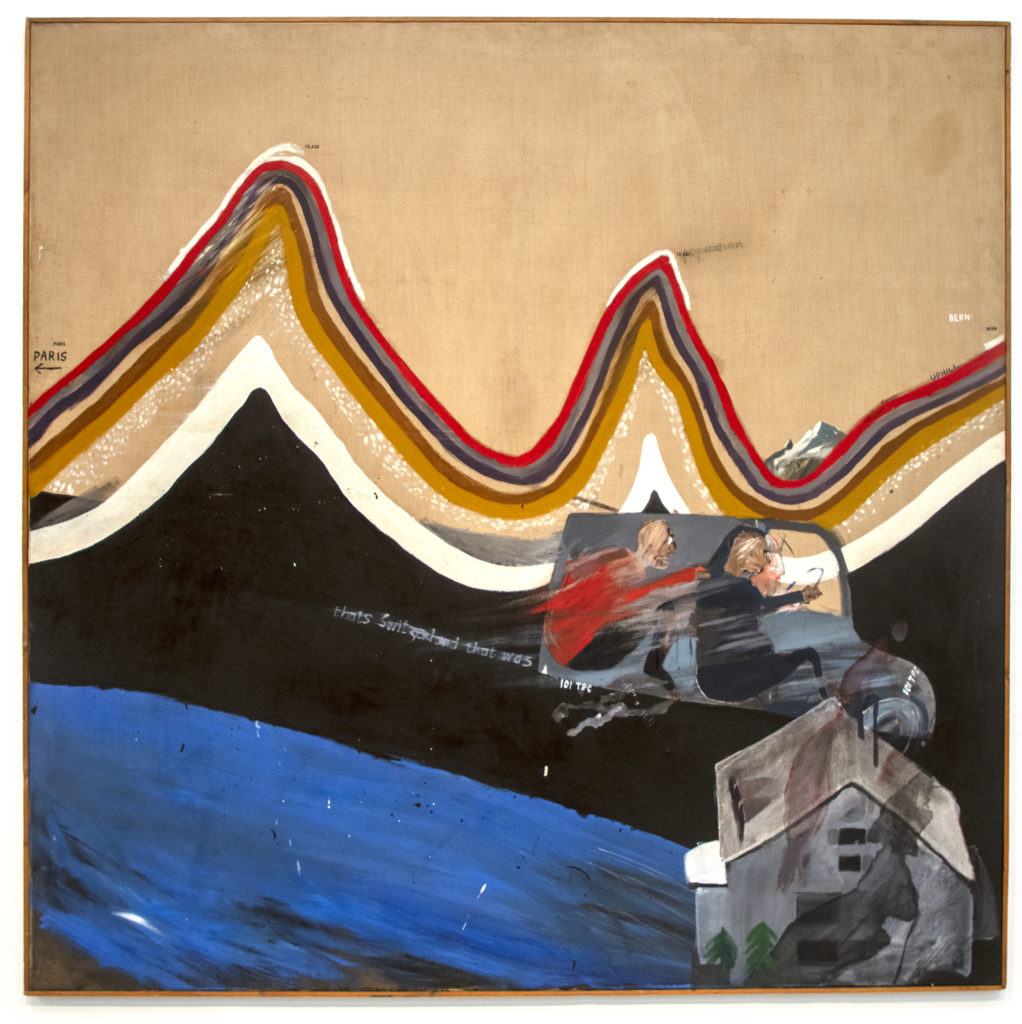

Flight into Italy – Swiss Landscape 1962 David Hockney Oil on Canvas 72 x 72 inches

Helen Kapp corresponded with Hockney who was not shy in approaching those he thought could help further his career. A student in Bradford it is believed Hockney attended talks that Davie gave at the Wakefield gallery, and this show demonstrates clearly the kind of links and influence that ties these early works together. I find Davie’s paintings to be full of life, wit and vigour, a delightful revelation from the rather dry presentations I have seen of them in the past. Indeed, the comparisons that are invited by this hang of the works of both side by side favour, I think, Alan Davie rather than the early Hockney.

One of my tutors when I first went to art college in 1966 had been at the Royal college at the same time as Hockney, telling me that his sense of timing was the one characteristic that set him apart from his fellow students. She told me a tale of how, one wet day, the Queen was processing past the RCA, under drizzly sky, with a small cheering crowd lining the pavements. As she passed the Albert Memorial David Hockney appeared on its steps in his gold lamé jacket. He was struck by a solitary ray of sunshine and this attracted the attention of the crowd who turned to stare at him, missing the Queen as she passed their turned backs…

Certainly, this work shows the Hockney of the late 1950’s early 1960’s to be more cerebral than the vigorous expressive qualities apparent in Alan Davie’s works. In both the work revolves around their sexuality. Derek Boshier, in an essay for the catalogue says:” We weren’t interested in Technology, we were interested in popular culture: girls films, boys films. I remember seeing all the Dean Martin films, musicals, Doris Day, a lot of cowboy films” The catalogue has a series of interviews of people who were involved with the artists and they paint a portrait of life as students at the Royal college in its glory years, a portrait the portrays a culture familiar to us that followed on in art colleges in the later 60’s.

It is sometimes said by historians that every Empire finishes with a burst of brilliant creativity. If this is the case then in our national decline the brilliance of these two artists shine brightly in the cultural firmament. The show represents their early years, years that appear to be more brilliant for Davie than they were for a Hockney still seeking to come to a balance between the prevailing modes of abstraction and the new burgeoning of realism. Whilst Davie wholeheartedly embraced the working methods of abstract expressionists such as Jackson Pollock, Hockney was already starting a journey to becoming on of the greatest of contemporary realist painters in a tradition that stretches along a road parallel to abstraction. Whilst the path to Pollock can be traced through Impressionism, Cubism and Futurist works leading via artists such as Ben Nicholson and Adrian Heath to the cerebral abstractions of a Bridget Riley, Realism followed an American path through Hopper and the American Prairie School like Wyeth. Hockney’s slower progression through his own discoveries led to an intelligent fusion of the two and is the reason his work shines so brightly amongst the dross of much of today’s art market.

The contrast revealed in this beautiful little exhibition is the contrast between instinctive emotional revelation of an artist’s unconscious on the part of Davie versus the struggle to rationalise that emotion with his intellect that is expressed in the tighter work of Hockney. Paintings such as Davie’s ‘Good Morning my Sweet’ are almost banal in the imagery that is obviously visceral and emotive and reflect the direct working from the heart and soul of the artist. In that directness lies the seed of Davie’s eclipse, as the painting comes from the gut with the intellect very subordinate.

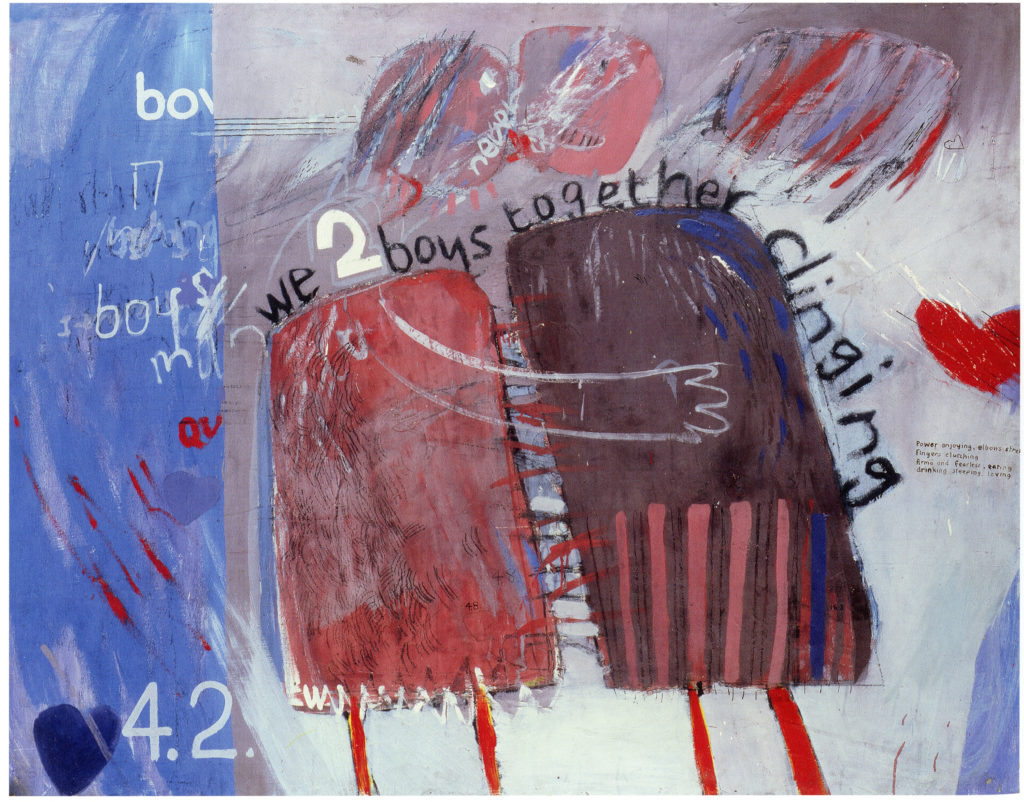

By comparison paintings such as Hockney’s ‘We Two Boys Together Clinging’ carry his sexuality but with an almost winsome awareness, in part expressed through the addition of words to the images. This difference grows through the years as Hockney battles to balance abstraction and realism, creating visual tensions in his works missing from Davie. Whilst Davie portrays fierce energy and emotion Hockney continues to coolly work out his approach with a driving thoughtfulness that has become clear over the years through his broadcasts and writing. We Two Boys Clinging Together 1961 David Hockney oil on board 48 x 60 inches

We Two Boys Clinging Together 1961 David Hockney oil on board 48 x 60 inches

For those unfamiliar with Davie this show will come as a revelation of his quality, vitality and sheer ‘joi de vivre’ that he expresses in the paintings. That he died ‘in obscurity’ in 2014 is sad as he was a remarkable artist, whose influence on Hockney is drawn out throughout this show. Although the similarities in approach may be as much a product of the time and shared experience through attendance at the RCA, we would not begin to be able to analyse it without the work of Helen Kapp and her successor curators at both the Hepworth and the Towner.

This is a not to be missed show, and if it and the Nash are harbingers of what is to come from the Towner then we are into a true flowering for the arts in Eastbourne. If we are in a final ‘burst of creativity’ at the end of Empire, then note the historians reckon it last 50 years. Britain finally said goodbye to Empire, according to Wikipedia, in 1997 with the handing back of Hong Kong to China. If that is so I reckon we have another 30 or so years of pleasure ahead. Of course, if you date the end of Empire from Indian independence (1947) then it’s already all over, bar the shouting…. Crazy Gondolier 1960 Alan Davie Oil on Canvas 72 x 96 inches

Crazy Gondolier 1960 Alan Davie Oil on Canvas 72 x 96 inches

Recent Comments