My Workshop experience

Understanding workshop experience of nearly 100 years ago without access to original sources is difficult. My own experience probably stands in stark contrast with that of a student at the Bauhaus. Life would have been very different for a Bauhaus student amongst the political activism and rampant inflation of a demoralised Germany in the 1920’s to that of an art student among the revolutionary social changes of 1960’s Britain. Germany remained a fractured country under partially foreign occupation and burdened with war reparations. In Britain the music, writing, fashion etc. all were bursting out of a generation also free from the shadow of war, with 1966 being the first year a British soldier had not been killed in action somewhere since about 1750. Both were out of the shadow of war, but one repressed politically and economically, whilst the other was exploding with optimism free of its colonies and the Imperial burden.

I studied on a fine art painting workshop programme that may have paralleled that of the Bauhaus, and offers an example of how disciplines, explorations, and structured programmes can lead to advances and eventually expressive and creative freedom for the individual. I believe that the course set up at Corsham in the 1960s, a prototype for many degree programmes, was largely structured by Clifford Ellis along the lines of the Bauhaus programmes. Although some of my fellow students from the period disagree with me. My experience of the course is obviously restricted to my own discipline, and a fellow student at the time in another workshop area, graphics, remembers it differently. Steve, who went on to partner with another student and on to designing items such as the new Icelandic currency notes, comments:

“I have read your Bauhaus writings with great interest, but I think I can see little to connect Bauhaus methods with the Graphics (“Visual Communication”) course at Corsham. Many of the tutors were totally incompetent and Rosemary Ellis, who was Head of Department, was a mannerless beast and thoroughly disliked.

Looking back, I think I got most out of the technical side of things.

Corsham’s technical facilities were excellent and what I learned there has served me in very good stead throughout my career.”

Clifford and his wife, the fearsome Rosemary, were graphic designers in the 1920’s and 30’s, working on the well known Shell campaigns amongst others, so their interests were different to those of the architecturally trained Gropius, but they brought both rigour to structures and creative individuals to teach, inevitably building in the same creative tensions that characterised the Bauhaus, shown in the writings of Schlemmer and others. Corsham too suffered Nazi influence, but to its unintended benefit. Bombed out of its home in Bath during a so-called Baedeker air raid, it was offered the space at Lord Methuen RA’s estate in Corsham, where students studied in an Inigo Jones house amongst grounds landscaped by Capability Brown.

In their sylvan environment students were encouraged to be in the studio seven days a week giving an intensity of experience and an opportunity to learn outside the tutored 33 hours a week they received. Students lived in hostels, a community of young and excited and exciting individuals immured in a small village where they largely enjoyed making their own entertainment although TV common rooms filled to overflowing for arts and music programmes. Composer Michael Tippet, a village resident, once confided in me that he sunbathed in his garden adjacent to a hostel ‘waiting for one of you lovely boys to jump over the wall and join me’.

The tutored hours were structured around teaching teams, enabling students to almost choose who they worked with. I can only really talk about my own experience in this workshop environment, where my ‘team’ was Michael Kidner, Malcolm Hughes, Adrian Heath and William Tillyer. I had some contact with Michael Simpson, Stephen Russ and Mark Lancaster but they were peripheral to my interests. The location an its isolation made for an intensity of experience that reputedly gave the college one of the highest mental breakdown rates of any college in England. For a Bauhaus student in the febrile political atmosphere of the Weimar Republic and the rise of Nazism the experience must have been even more intense.

In the Bauhaus the ‘Vorkurs’ course led on to the workshop (journeyman) programme and thence to the master craftsman exams. Presumably like our own foundation courses, Vorkurs also weeded out those students for whom the creative demands of art and design were not suitable. Beyond was the world of increasing specialisation focussed on one discipline. Today these discipline areas are defined in roughly four broad specialisations – Fine Art, 3d design, Graphics and Fashion. These are very broad churches covering a wide range of areas from painting to electronic arts, stonemasonry to event structures, animation through to woodcarving, interior architecture to jewellery. With over 45 disciplines to choose from today the need for an early diagnostic programme has never been more important to clarify both the students aims and to identify where thinking and skills indicated best destination might lie.

In the Bauhaus workshops were structured, according to Magdalena Droste, with a clear hierarchical structure. She says Gropius

“stipulated ‘model work’ should be their key objective, meaning that prototypes were to be developed for industrial production. Thus the workshops became places of both instruction and production, and a limited company responsible for the sale of products was set up in October 1925”

From ’Anni Albers’ pub.Tate Enterprise 2018

Efforts to link modern day design courses with industry have been limited and have often been opposed by the design industry as being unfair subsidised competition. This is unlike the successful University model of research and innovation that has led to considerable success for major UK institutions such as Surrey’s successful space programme or the biochemistry industry around Cambridge. My own experience suggests that the design companies have been mostly too small to collaborate meaningfully with colleges.

Manufacturers in the UK are generally myopic in their attitude to design, ceding industrial leadership to Japanese, Korean French and German manufacturers who often are led by UK trained designers. Ironically, I did a presentation on the UK art college structures, on behalf of my professional design body, to design directors from leading industry companies in Japan who could not understand why Britain produced so many creative individuals and wanted to replicate that in Japan. Ironic because our own industrial companies are so reluctant to bring design into focus at board level where it could contribute to leadership in innovation as Morris and others did in the 19th century. Even more ironic now when our education system has destroyed much of what the Japanese admired and would wish to emulate about out art college system.

The use of part-time lecturers in colleges is based on the idea that practitioners would share current practice and pass on information current to industrial practice, whether in art, design or manufacturing. Unfortunately, it has been used to keep pay levels down, so those most involved in industry, the high flyers, are often unwilling to give up lucrative work to be involved in college courses. In fine art this is the reverse as dedicated artists frequently are unable to sustain their art practice without a steady income and want to pursue their artistic enquiry free of commercial pressure. Part time teaching enables this, even at the risk of student sucking the creativity out of the lecturer. Those artists that achieve recognition and sell at high prices also then become reluctant to spend time in a college environment.

I was lucky. Established painters like Adrian Heath were not only willing and able to devote themselves to some teaching at Corsham, but also structured the learning to develop skills. I showed in an earlier post a sample colour exercise introduced by Michael Kidner. One of Adrian’s life drawing days could start by him saying that we were to use only 8 lines on a sheet of A1, and that each line should go from one edge to an opposing edge. The model was to ‘emerge’ from the resultant crossovers. He developed our understanding of using colour by encouraging us to code the resultant space with it.

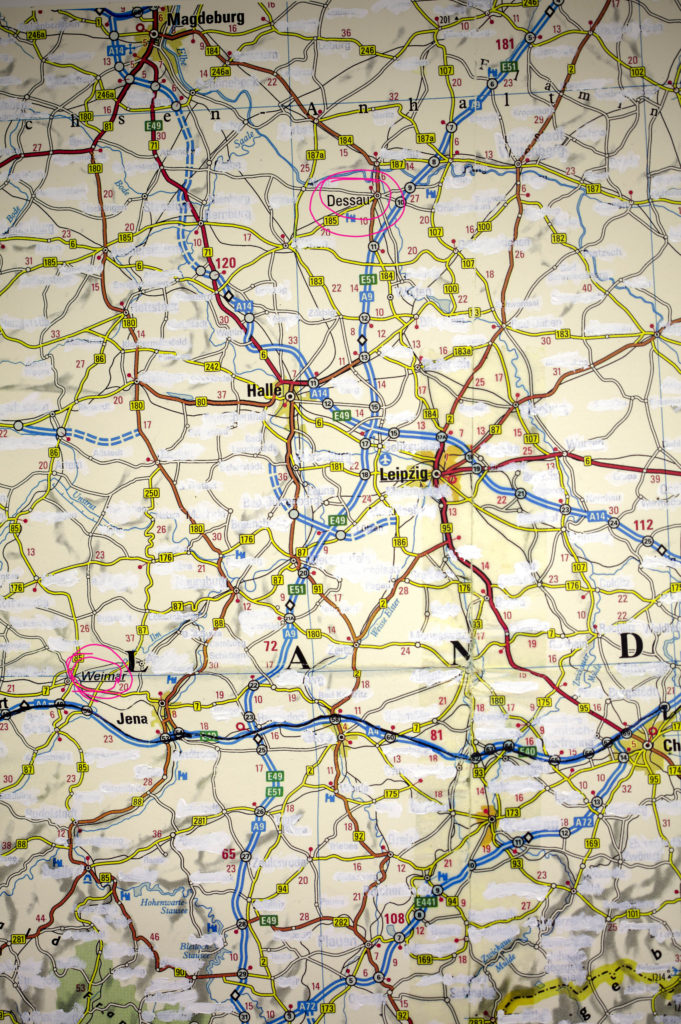

map showing the relative positions of Weimar and Dessau. Berlin lies off the map to the north but Weimar was briefly capital of the Weimar Republic

Additionally, the college would link us in with working artists. I spent time working as studio assistant to both Adrian Heath and John Hoyland, whilst one of my flat-mates worked for Richard Smith. The exposure to their studio lives was the equivalent to the industrial placement practiced on some degree programmes in the design sphere. I know of no fine art course that currently includes this kind of exposure in their course programmes. Indeed, I think most courses fear allowing students to experience ways of working elsewhere in case it contradicts the information the student receives on their course programme.

As art and design courses are threatened by forces from either within or outside of their institution, they tend to curl inwards protectively. The advantage that Gropius and his successors had was that they ran an institution that was dedicated to the art, from architecture through to weaving. They understood and fostered lateral thinking and its role in creativity, innovation and design. They understood the relationship between disciplines. They were free of academic oversight and bureaucracy able to innovate, setting a lesson for other learning institutions. The question for art staffs today is how to engender change within qualification and cost obsessed institutions.

As they quaffed the champagne in Berlin in 1933, the Bauhaus staff and students must have viewed the future with trepidation, much as students do on leaving their degree programmes today. I have detailed some of my experience in previous blogs here. Future blogs will look again at how my path and that of the Bauhaus continually crossed paths.

Meanwhile you can follow me on Twitter or Facebook

To see the other essays in this series follow the links below:

What intrigues me about Bauhaus is the strong connection between original Jugendstil or Arts and Craft adepts and Bauhaus adepts and the international network including the USA later by the fleeing of many bauhaus adepts to the USA.

Great writing and educating me again and again. My knowledge of Bauhaus is a lot lesser than yours. Love reading. Thank u for sharing.