I have been a collector most of my life. At ten I was collecting matchbox toys. At 12 it was British and Commonwealth postage stamps. At 16 it was Cypriot wine bottle labels. In art college, I began looking at collecting the work of other artists, starting with work by friends like Geoff Turpin. This expanded into trying to buy the work of established ’names’, underpinned by the feeling that the only way I could hang my work on the same wall as, say, Patrick Caulfield, was to buy a work of his to hang alongside mine at home.

Bought for £40, this print was my major artist acquisition in 1978. It spoke to me of camping trips though the French vineyards, of summer sun and pleasure. Originally produced by Waddington Graphics in an edition of 100, there were 15 proofs, some obviously going to the printer, Chris Prater of Kelpra, and thence to me. Chris and his wife Rose are credited with being the pairing that put silkscreen on a professional artistic footing for the first time. I worked for a year as a commercial printer, alongside other jobs, and to me having a Prater printers proof was more meaningful that just a print from the edition. Collection Towner Gallery, Eastbourne

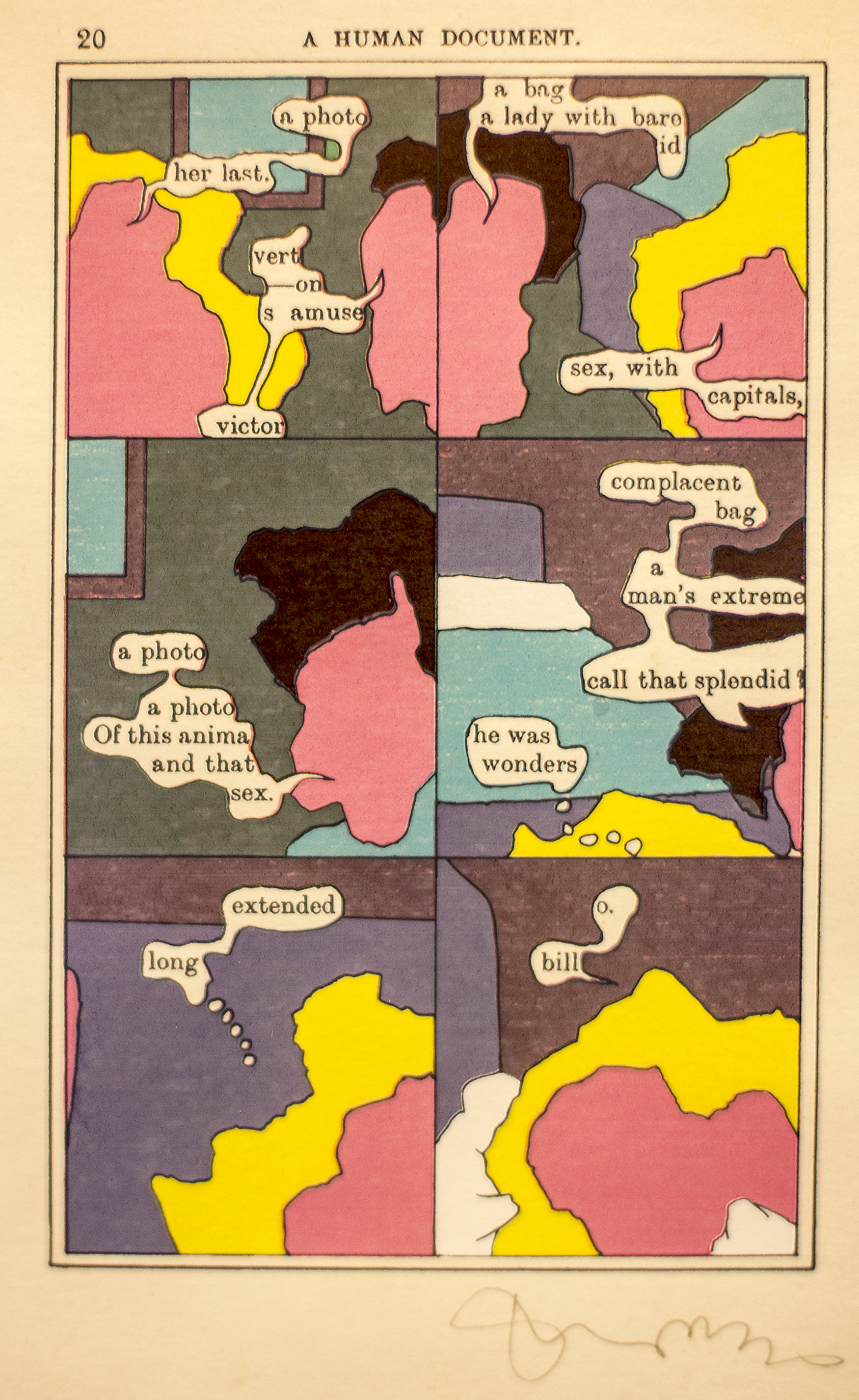

The prints later also became a teaching tool for art college students, taking them in to college so that students saw not just slides or pictures in a book but the actual art pieces, for example letting them hold a Tom Phillips ‘Page from the Humument’ as they learned about him from a lecture. The scale of prints, the feel of the paper, was an experience quite different and more magical than seeing reproductions.

There was a Tom Philips Exhibition in the then Peterloo Gallery in Manchester in April 1977. When the show was being hung, Lillian Gethic, the Gallery Director invited me to take up the ‘little gallery’ space not being used for the main show. Obviously I was delighted to be asked to show alongside on of the major artists of the day. When the show was being taken down by TP’s assistant there was a panel full of pages from the Humument. Idly almost I asked what sort of deal he could give me on them and was told ‘a fiver each’ but if I paid £20 I could have five. I chose five on the spot, and these were delivered later. Collection Towner Gallery Eastbourne

As a onetime screen printer, teaching screen-print processes, my aim was to show the range of use of the medium by artists. I also wanted to contrast it with other process too, so the collection was supplemented with chance acquisitions of etchings, woodcuts and lithographs.

Above all, whilst I bought what I loved I also bought things I thought were of unmistakeable artistic quality, without necessarily knowing what they were or who they were by. I bought what I liked – the first rule of collecting.

The definition of an artist print has changed many times, so before talking more about my collecting habit I must pause to define exactly what I consider an artist print to be. The most authoritative work on this was Pat Gilmour’s ‘Understanding Prints: contemporary guide’ published by Waddington Galleries in 1979, which summarised much of what I learned as a student, and which remains a good guide to collecting today. Some things have changed dramatically since so I have refined slightly and added to her definitions, leaving me with:

· Relief print: made by removing material to leave a ridge standing proud to take the ink for transfer to paper such as a lino print or a woodcut

Woodblock print ‘Wave’ by Merlyn Chesterman. Merlyn grew up in Hong Kong, and studied with me in the same group at Corsham, under Adrian Heath and William Tillyer. Merlyn became a woodblock printmaker in 2000, after a visit to Northern China. She has work in the collections of the V&A in London, The Ashmolean in Oxford, The Edward James Foundation at West Dean College, and with private collectors. Collection Towner Gallery Eastbourne

· Etching or intaglio print: made by incising or biting with acid into metal to take ink for transfer to paper

Terence Millington etching of Chateau Leoville Barton. An etching from the ‘Wine Arts’ series of commissioned prints by leading artists, each doing a different Chateau. This piece was won in a raffle! Collection Towner Gallery Eastbourne

· Litho: a greasy image made onto a porous surface, traditionally porous limestone, more recently a grained alloy or plastic plate. Traditional stones came from a particular Bavarian limestone quarry, and were sensitised by grinding their surfaces with fine sand between two stones – a task I remember as a labour as a student, loved by some, loathed by others

This litho by Charles Spencer Pryse was discovered covered in cobwebs at the back of a blacksmiths. Bought for £25 it is a printers proof. The artist was a Belgium government was artist in WW1, famed for his posters for the labour party pre that war. Collection Towner Gallery Eastbourne

· Screen-print: an open stretched woven mesh blocked out to allow ink only through open areas – possibly the only print process that allows opaque white to be printed onto dark colour, and also capable of printing on a variety of surface types

New York Decals No. 1 and No. 2 by Joe Tilson. Purchased 1978, now in the collection of the Towner Gallery Eastbourne. no.1/10 in the edition

· Giclée: basically ink jet printing (snob title in the way ‘serigraph’ was used for a while to describe screen-prints). Images should be made specifically for print, but often used for copying and reproducing images from photographs, the web etc., none of which should form part of an ‘artist prints’ collection, lacking in originality and authenticity.

William Tillyer. A poor reproduction I’m afraid, but ‘Willy Tilly’ is a pioneer of the use of large scale giclee printers. Collection Towner gallery Eastbourne

In all these processes the collector should look for results which will stand the test of time. This would include terms such as ‘archival’, ‘museum quality’, ‘acid free’ etc. After all one expects collected works of art to last at least one lifetime but really one should expect to be able to pass them down to future generations, not have them decay or disintegrate.

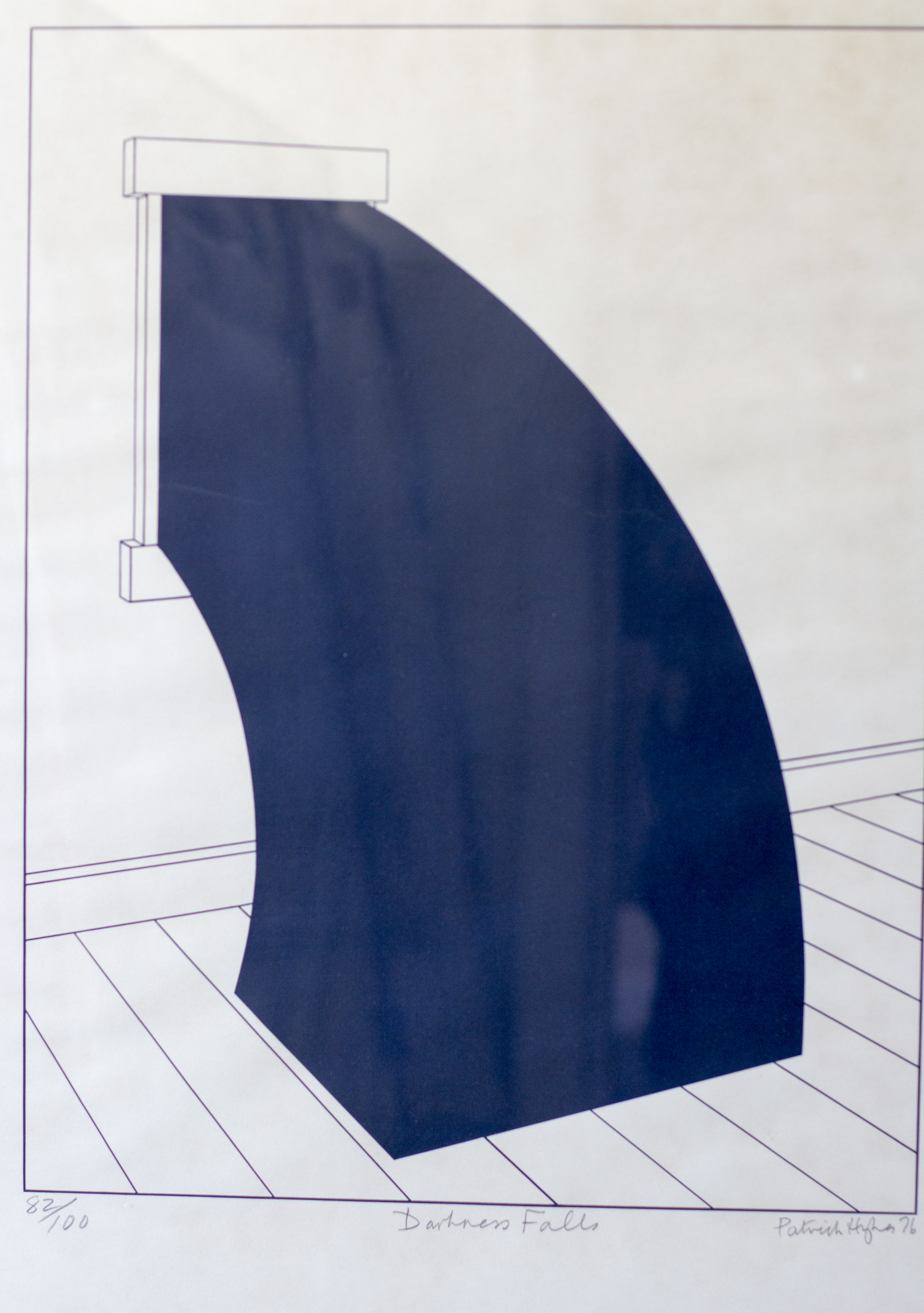

Darkness Falls, a screenprint by Patrick Hughes. Printed on lousy quality poster paper already changing colour. Collection Towner Gallery Eastbourne

Prints are produced sometimes by the artist working alone, sometimes in collaboration with an expert printer in his workshop, and sometimes by a printer working with the artists information (drawings etc.) but without direct input by the artist. Traditionally the printer would show his best efforts to the artist who would signify that this was the standard all other prints should meet by signing the print, this becoming the artists’ proof that it met his standard. Likewise the printer would also sign the proof print to show it met his technical standards. Often both signatures would be present. Over the years these proof prints became bonuses for the artist and printer to sell, sometimes referred to as ‘hors de commerce’ as they were not normally sold through a gallery.

These printers proofs and artists proofs were my target buys, as not being a part of the commercial edition, they were often available without gallery mark up or commission and therefore considerably cheaper. I also like those marked printers proof with the artists signatures as to me having both parties signing added value, even where the print was not a part of the ‘official’ edition.

Hiroshige – one of 36 views of Mt. Fuji. One of the two most important Japanese printmakers of the 19th century, influencing Monet amongst others, this was rescued from a rubbish tip and restored by students. nil cost! now in the collection of the Towner Gallery Eastbourne. Another of my poor record photos taken through glass

So how was an edition defined? Once upon a time it was what could be produced before the litho stone or etching plate deteriorated to the point where the end result was not acceptable. The prints then offered were numbered to show how many had been produced and at what point in a run that print came from. Thus 1/10 showed it was the first print in an edition of ten. Often the knowledgeable collector would want the first of an edition on the basis that this had the best, finest, quality.

With so many print processes being improved and commercialised, print runs of thousands became possible at which point the Inland Revenue intervened, saying that anything over 125 in number was a reproduction not a limited edition and therefore subject to Purchase Tax (a precursor to VAT). Artists then voluntarily limited edition numbers to avoid tax.

Screenprint entitled ‘Snip Snip’ by Terence Warren, edition of some 5,000 issued bound into copies of Arts Review magazine in the 1970’s

At the end of the numbered run the printer would destroy the plate/stone/screen to ensure no further prints could be produced outside the ‘limited edition’. Photographers, for example, often guarantee the number of prints to be made of an image in the spirit of producing a ‘limited edition’, in older times destroying the negative to ensure this happened. This is something that has become much more difficult to guarantee in these days of high quality scanners and digital processes, with fraudulent copies around.

Traditional media leave a mark quite different in nature to that produced by the giclée or digital photo print, the print usually betraying by its surface the means by which it was produced. Digital images themselves can be date stamped and digitally marked to prevent unlicensed copying. Techniques introduced in the 1950’s and 60’s saw more industrial production techniques used, epitomised by Warhol’s ‘factory’ where he and his friends would produce 80 works a day, not all of which were touched by Warhol’s hand.

Collectors need to be sharp eyed and sharp witted in making their collections, and not all worthwhile acquisitions need be made through traditional art routes as some of these examples from my own collection, which illustrate this article, show. I used them here as an example of how a significant small collection can be made with determination and a sharp eye.

Most of my artworks have been donated to Eastbourne’s Towner Gallery, now forming part of their collection. There are over 30 prints in the collection, including works by Patrick Caulfield, Joe Tilson, Tom Philips, Peter Philips, Andy Warhol, Gerd Winner, Charles Spencer-Pryce, Hiroshige, Terence Warren, Terry Millington, Merlyn Chesterman and Patrick Hughes.

You can follow me on twitter

You can see my work progressing through my studio on Facebook

You can buy my prints, collages and paintings from my Gallery

Recent Comments