Just over a year since my last visit to the Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft, I make the jaunt again, this time to see a more in-depth look at the work of Eric Gill (1882 – 1940). Much controversy surrounded this exhibition because of Gill’s sexual activities with his children, and the museum asks if you are aware of this when you buy your ticket. It angers me that the abusive behaviour of the artist invites dismissal of his work through our social moral outrage. If we applied this to the sexual deviancy of many other artists then warning should be given before looking at the drug addled output of Warhol, or what Griselda Pollock¹ refers to as the ‘sexual tourism’ of Gaugin and his sexual exploitation of South Sea islanders.

Equally capable of adverse moral judgements are the peccadillos of Rodin, and Lautrec. Hockney could have been prosecuted in the 1950’s and the mistresses and wife swapping of the Pre-Raphaelites and Ravillious alike would have been the cause of moral outrage in their time, similar to the Victorian moral outrage over the suggestive nudes of Alma-Tadema. Our manufactured emoting over historic misdeeds may satisfy a prurient feeling of moral superiority, but I do not believe it should influence our appreciation of the art, although it may generate momentary shivers of revulsion. I do not defend the behaviour of Gill – child abuse should be a capital offence.

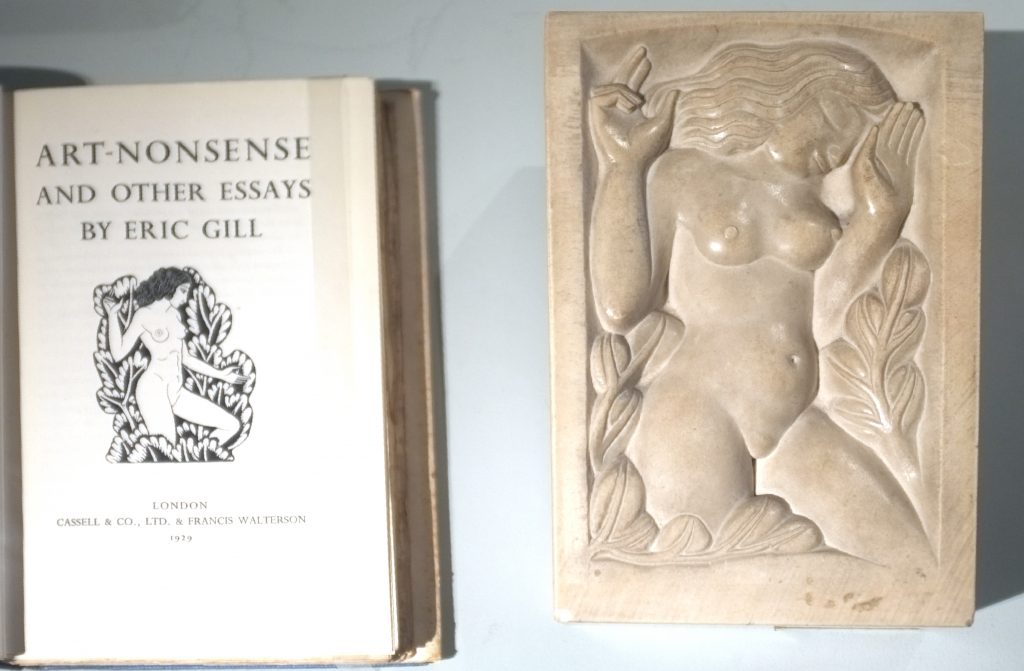

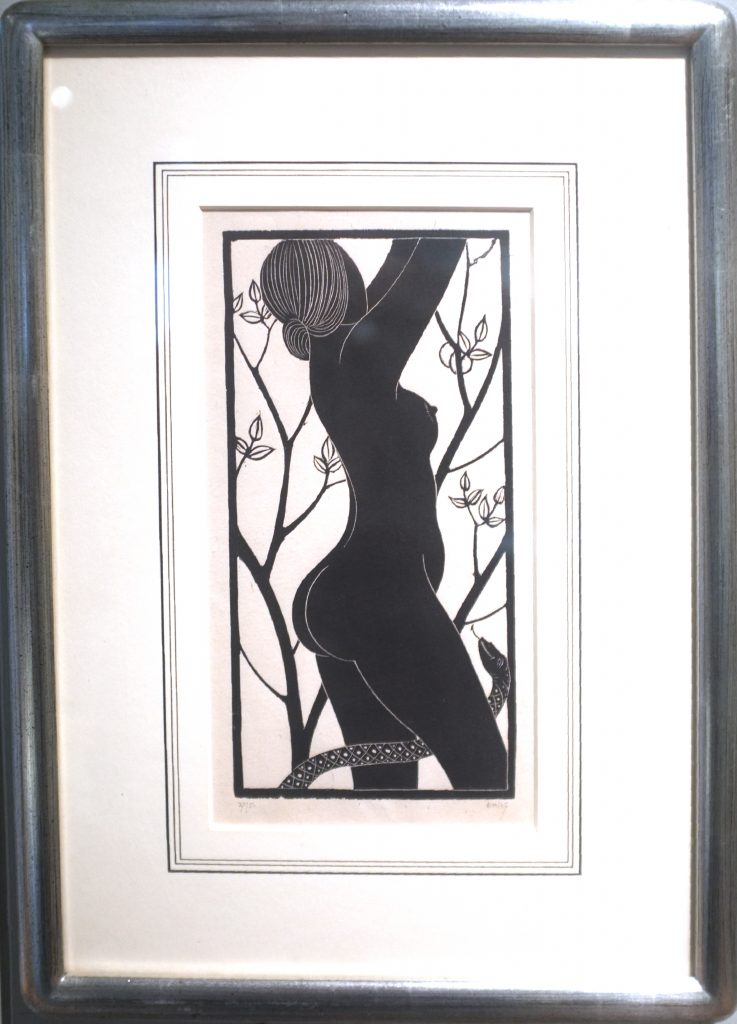

Art stands alone from its creator surely? Many like, for example, Caravaggio, have fled from justice for heinous crimes, but their canvases advanced the frontiers of art in ways that benefitted all humanity. So, does the art of Eric Gill do this? He is hailed for his abilities as a typographer, but as my previous piece showed much of this change is down to collaboration with others, notably Johnston. This time the Ditchling museum focusses on his drawing and sculpture. Much of the drawing shows itself to be in the mainstream of black and white illustration, owing I think much to the work of Aubrey Beardsley, and, despite the warnings, lacks much of the pornographic qualities of Beardsley drawings for ‘Lysistrata’ or the ‘Rape of the Lock’.

The drawings mostly lack any scale which again diminishes them, although one or two drawings that are larger bring a smile from the manner line and shade bring emphasis to a hip or thigh, echoing the sexuality and subtlety of the sculpture. Most of the drawings relate to printed works and are so much tighter or constrained in their execution than the life drawings are – I would love to see more of his larger more sensitive and expressive life drawing pieces.

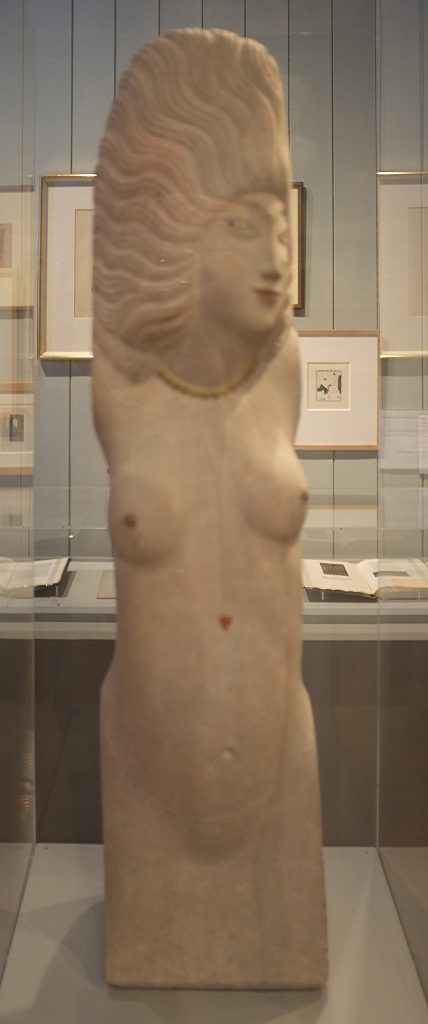

It is in his handling of stone that his real sensitivity surfaces. The museum script eulogises his sinuous carving of hair, but the sensuousness of surface is what entranced me. Rodin is reported to have fondled his models then the stone he was working, and it may be of course that this was the case too with Gill in his working. In both cases the results were remarkable. Gill’s religious sculptures triumph in their narrative form but the addition of red lipstick colouring on the stone take Gill’s secular sculpture from the sublime towards a more uncomfortable and perhaps decadent reality.

Much of Gills output was in response to public commissions for the likes of Westminster Cathedral, the League of Nations and the BBC (plenty of decadence and prurience there), but this show has managed to assemble 80 pieces of work, much of it from the Museums own collections but some on loan. It is introduced by a large piece by Cathie Pilkington, the professor of Sculpture at the RA Schools. This piece itself is homage to Gill’s daughter Petra, one of the subjects of his abuse.

Does Gill advance our understanding of the sculptural form? It does not stand him alongside the likes of Rodin, nor place him in the forefront of innovation like Moore or Hepworth, but does emphasise his position as a master carver, and a stand-out master of English sculpture in the first half of the 20th Century. The show is well worth the trip to Ditchling if you can leave your moral outrage at home.

Eric Gill: The Body until 3 September

¹ See ‘Avant-Garde Gambits 1888 – 1893: Gender and the Colour of Art History’ Griselda Pollock 1992

thanks for this post. Like you, I tend to regard the art work as separate from the artist life, although some invite you into their lives via their work, ie Frida Kahlo. Even, then that is only a glimpse into their lives. We all carry secrets.

Although I discovered Gill’s work by chance about 20 yrs ago, not sure I have actually ‘seen’ it despite working past it for several years as I passed by Broadcasting House going to work in London.

I read an article that it should all be destroyed like the work of Rolf Harris and all reference to Jimmy Saville should be scrubbed from the archive of the BBC. But then, you consigned the plight of the victims to the darkness and other will become victims because it has been swept under the carpet. Human ethics change with time. In Egyptian times, I am sure, Gill would have been consider quite normal even if its repugnant to us now. Only got to look at the Bathroom row in Texas, to see how these things evolve. 🙁 I am looking forward to wearing my hair in long plaits contained by a headscarf with my long shapeless dress and clogs when Pence becomes President 🙁 I wonder what his dirty secret is?