The writing was on the wall in Europe long before 1939. Hitler came to power in 1933, the culmination of a series of economic and political catastrophes across Europe. Churchill warned a complacent British political class (aren’t they always?) of the dangers on the Continent urging rearmament, but his was a ‘noise off’ as far as government was concerned. Working in the Stedelijk Museum from 1928, then not the grand establishment of today but a five decade old gallery supporting practising art in Amsterdam, Sandberg was one of the museums curators and took part in helping artists, dealers and collectors fleeing Germany find refuge for their collections. The museum also bought works from them including work by Paul Klee.

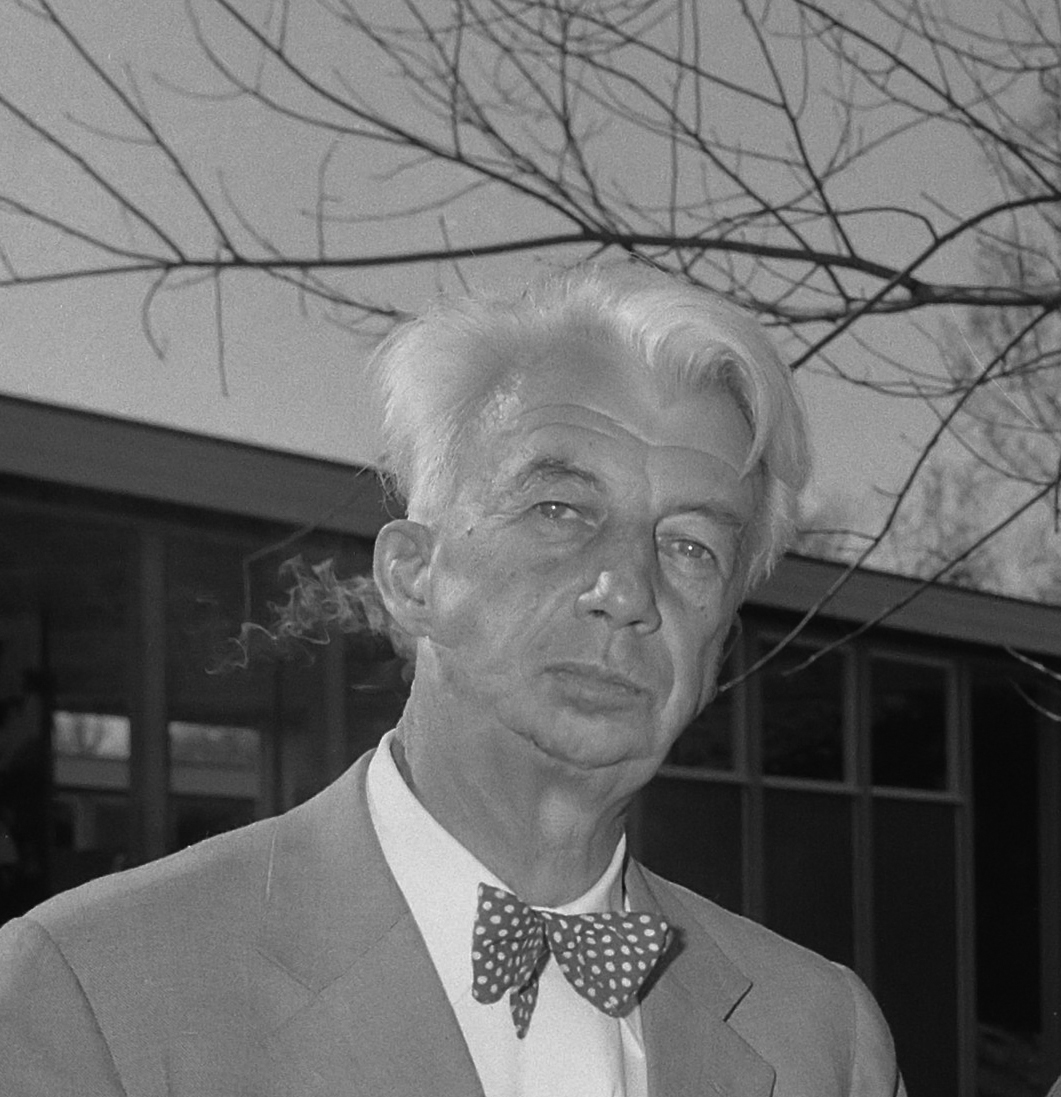

Always an independent thinker, Sandberg served his national service in the Coast Guard after refusing to take an oath of loyalty to his Queen. Visiting Spain in 1938 Sandberg saw the effects of bombing and immediately on his return encouraged the museum to construct a concealed bunker in the dunes near Castricum for safe storage of collections during war. His prescience was justified when German armies rolled into the country in 1940. The bunker housed work from many private Jewish collections, which were not recorded under the owners names to protect their provenance, creating some difficulties after the war in effectively restoring works to their original owners or surviving family members.

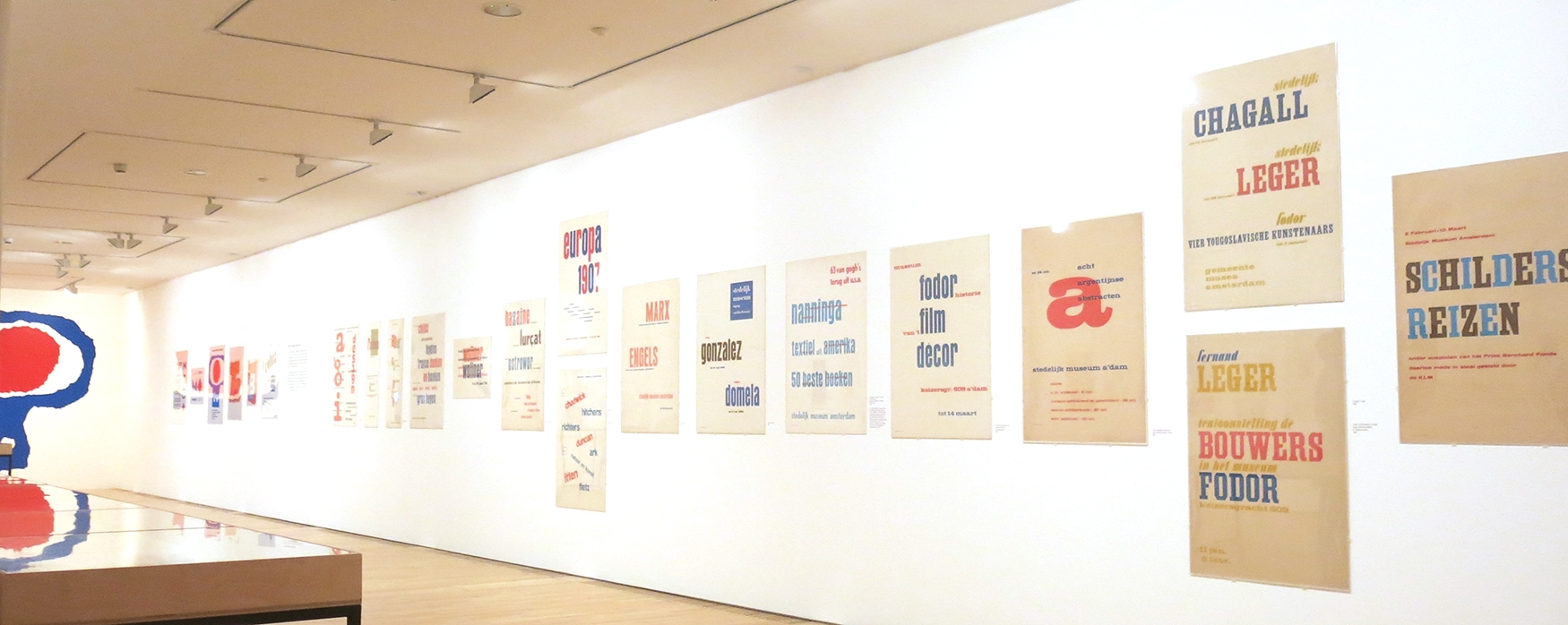

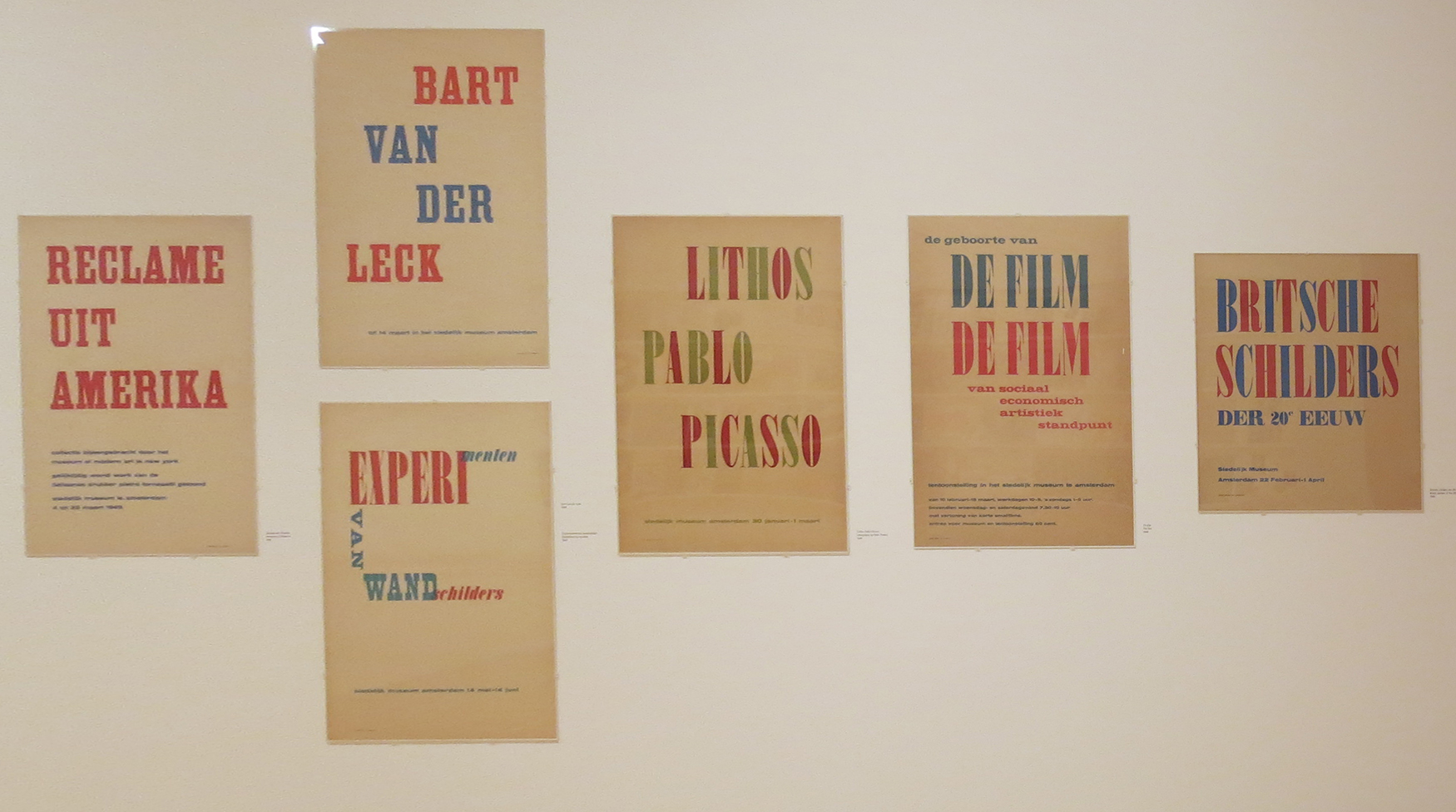

Sandberg was a part of a resistance movement using his graphic skills to forge identity papers to protect hunted residents from the Nazi police. He organised resistance in subtler ways from 1938, putting on exhibitions of decadent art as a riposte to German sponsored art exhibitions, including some of the first exhibitions of abstract art in a major museum. He used the purchasing and exhibition budgets of the museum to support artists who were not approved by the occupiers and who found it difficult to making a living without that official endorsement. His contract as curator ensured he retained design responsibility for the catalogues, and he also commissioned work from Johannes Itten of Bauhaus fame, much of which was lost in the war.

When the Central Records Office started to be used to compare names on forged documents with lists of real people, Sandberg was part of a group who succeeded in destroying it in 1943. His false papers were apparently indistinguishable from German identity documents, and without the registry of people to check against they were successful in keeping refugees safe. Unfortunately, the conspirators were betrayed but Sandbergs wife was able to warn him via a direct telephone line into the storage bunker and he escaped into hiding, his wife and son being imprisoned.

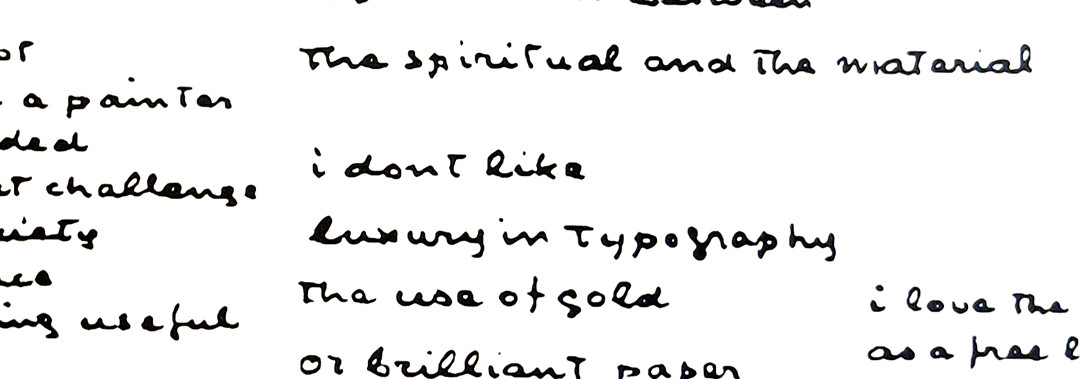

The Gestapo forced Sandberg into hiding for fifteen months under an assumed name. It was during this time that he made his experimenta typographica, hand-made booklets in which he collected inspirational quotes from his wide reading, and to which he added his comments in writing and in typography. In giving each quote a definite typographic character, Sandberg transformed his seemingly loose collections into intensely coherent stylistic meditations. Some of the booklets were later published using a mixture of type and hand-rendered elements. The first of these was published illegally in 1944.

Sandberg was forced to recycle materials and developed an intense and creative use of torn paper. The exhibitions shows the development of this work, its simplicity giving it great creative impact and laying the foundations for much postwar typography. His use of primary colours adds to the impact and he writes “I believe in warm printing and like vivid colours in particular red and blue, sometimes yellow. I dislike violet and green”

I used to work as a screen printer and taught the process for some years and the work here lends itself to the immediacy of that process, although most of the sheets here would be produced using lithography. The simple patterning and stencil like lettering reflect Sandbergs liking for simple materials and for using texture as a part of his expressive armoury. The show includes a large panel reproduction of Sandbergs handwriting clearly expressing his views.

There is a beauty to the typography and process he used alike. Working as the director of the Stedelijk Museum until 1968 Standberg produced hundreds of catalogues to shows he organised. He was responsible for a revolution in Museum design, being first to make the café a central part of the experience, creating children’s areas as well as creating innovative exhibitions. He campaigned relentlessly to give art and artists their rightful place in society through his activities in many organisations, institutions, advisory bodies etc.. He would have been outraged at the destruction of art education we have seen in England over the last 20 years by politicians, civil servants and unprincipled academics.

Sandberg died in 1984, a true creative and social hero. The show shows both the man and his work. It is small but beautifully formed and makes the trip to the de la Warr Pavilion well worthwhile. Curated by the Stedelijk Museum it is a great introduction to the work of this important pioneer.

In a mad world he stayed remarkable sane, and inspiration for all creatives

Very interesting