Art school in the 1960 has been mythologised by succeeding generations. I understand that, and also those who say if you can remember it you weren’t there. That myth paints a picture of institutions that had no rules, but that is completely wrong, and it is because of the rules there was so much challenging and innovating. As John Stuart Mill says in ‘On Liberty’ (I paraphrase) – ‘without rules there can be no challenges, freedom is the ability to break boundaries’. In Schlemmer’s Bauhaus rulebook the aim was to give students the tools to make the challenge and however inadvertently the introduction of the preliminary course in UK art schools did exactly that too.

“The academies of today allow their pupils freedom which they either cannot use or which they misuse for subjective whim; thus, they have ceased to be ground for revolution”

From Oscar Schlemmer: Man Ed.: Heimo Kuchling (a Bauhaus book)

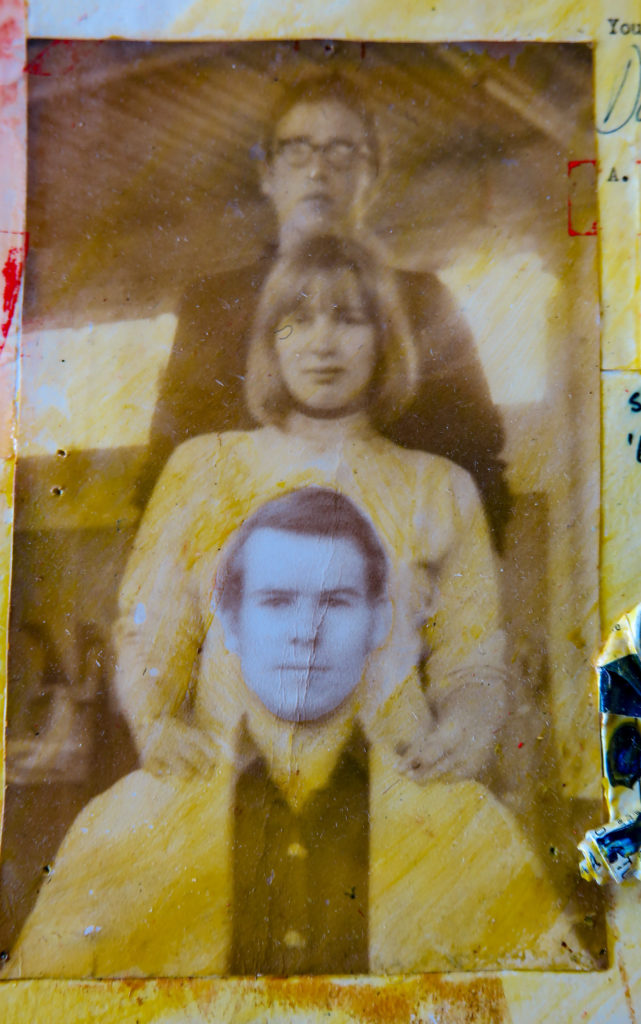

From top to bottom: Rick Clarke (now deceased) who created some of the worlds first liquid light shows; Dorothea who famously lip read remarks about her and exacted retribution; myself before my hair grew

A new world opened to me when I entered art college in 1965. Returning as a service brat from the Services school in Cyprus I joined the sixth form at Wellington Grammar in Shropshire. Starting at any school in the 6th is difficult, and I spent two years gathering bits and bobs of A and O levels without rhyme or reason before various adventures saw me arriving in Stafford art school half way through the first year of a two-year Pre-Diploma course alongside students completing the last ever exams for the old National Diploma in Design. I had mutated from a rule bound society that emphasised individual ability and initiative (the Forces) into a civilian world whose rules I did not understand.

The college course was set up to challenge. The first challenge to me was to move from a uniformed society into a dressed down and sometimes undressed circle; all this without drugs as the Huxley ‘Doors of Perception’/Tim Leary world didn’t kick in until later, peaking in its innocence with the movie ‘Easy Rider’ in 1969 before transitioning into the criminal world we have today. Life itself was enough of a challenge and the mental and physical transformation needed self-discipline and application as well as beer. Besides, art brings a heightened awareness far better than any drug can.

The course was also a transition from the rules of academia. Under previous courses students learned a formal practice by drawing from plaster cast and copying old masters. When the approach changed in the early sixties many casts were taken to the college roof and shattered by being thrown onto the ground below. Previous practice was based on the old atelier system, where artists learned in the studios of the masters, in turned based on the old craft schools for masons and carpenters etc.. The new pre-diploma and diploma courses (the prototypes of the new degrees), followed the Bauhaus in becoming anti-academic and seeking to create an atmosphere of intellectual challenge and questioning, encouraging creative freedom whilst inculcating an understanding of the discipline, techniques and practices need to express the ideas.

As in the Bauhaus, and as is made perfectly clear in Schlemmer’s diaries, the teaching required artists of vision and skill, and this in itself undermined any collegiate philosophical approach as competitive egos and artistic interpretation made collaborative programmes difficult to maintain. Indeed, Schlemmer is critical of Gropius, whose plans for the new Dessau building were purely architectural, excluding the integration of the visual and plastic arts in favour of ‘pure’ architecture – how often I was to experience this attitude from architects when working as a hotel designer years later. Schlemmer says:

“The building and architecture class, which was to have been the heart of Bauhaus, does not officially exist, instead there is Gropius’s private office. This sore and black spot is and always has been my anxiety. If the Bauhaus would profess itself a modern art school much would become clear. It is neither one thing nor the other, but perpetual unrest..”

From a letter of March 1922

Visiting Dessau and seeing that Klee and Kandinsky shared a house in which an orange colour was used in the interiors I could only laugh as I imagined the arguments between these two very different 20th Century masters. Despite this, the basic structure of the Bauhaus preparatory course with its subsequent three-year attachment to specialist workshop areas remains the model that survives in corrupted form in universities today. If I could make one improvement it would be to remove the Foundation course from any degree awarding college to ensure it becomes truly diagnostic not just a feeder to whatever few degree courses the institution offers. I would also make its completion a requirement before entry to a degree was allowed. This would have the added benefit of injecting revolutionary thought areas back into colleges in small towns across England from which they have largely disappeared.

As a student entering college from the closed world of air force bases the challenge to open up and think for oneself, to challenge ideas and engage not just in debate but also in creating work that challenged and expressed new ideas was a revolutionary step. Adding this to a social world which was also challenging, with students who went on to stellar careers in music, literature, film, fashion and a myriad of other creative areas. It was a heady mix. Mental in challenges to thought, physical in the new skills and crafts to be learned from welding and brazing, through grinding litho stones to pinhole photography as well as the social whirl. All was intoxicating.

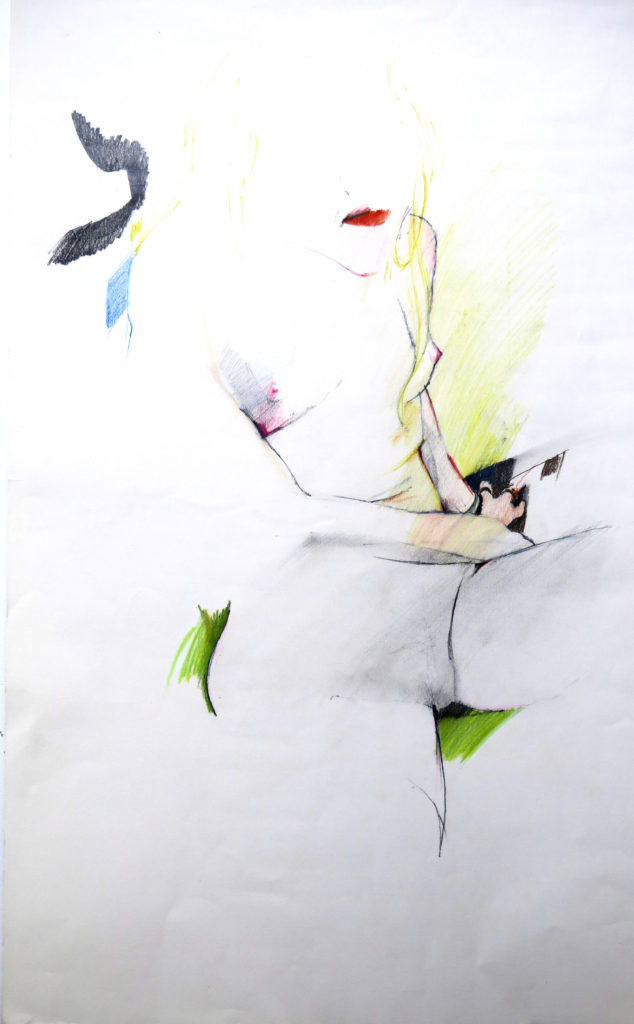

Drawing was the key skill. I set myself to fill sketch book pages every day – not scrap books as many students do today but setting myself tasks to do with mark making – using different media, left handed or right handed and many similar exercises in addition to the taught time in the studios, to build my own visual vocabulary. Life drawing was a key area taught according to the prescription of Oscar Schlemmer, started with looking for the lines representative of the internal forces within the body. The models varied from attractive 20-year-old women to a 60+year old overweight man, rumoured to be an ex-Army major, who was superb to draw. Only when mastery of proportions was attained was the expressive drawing of the figure developed.

“The problems which the Bauhaus painters saw confronting them as teachers were complex and exceedingly difficult to solve. No matter which angle it is viewed, art is unteachable”

From the Introduction to ‘Oskar Schlemmer: Man’

The employment of so many artists injected creativity as the Bauhaus made a major influence in modernising the world of design in parallel with the revolution in political thought taking place. Quite ironic when you consider the radical form of German socialism that was to ultimately destroy it, in the same way that Stalinist thought destroyed much of Russian artistic revolutionary activity. In both cases the training to challenge and innovate is what frightened the new powers. It was that development of the ability to challenge and innovate that the early foundation course dedicated itself to inculcating in students, whether in Dessau or Stafford. This inheritance has never been more under threat that in 21st century Britain and this blog series will trace the steady evolution of the menace.

“Some of these works may be making a plastic bomb to put under the liberal establishment chair of Western culture in which you may be sitting. Beware. This art makes you choose”

From ‘Modern Art and the Death of a Culture’ H.R. Rookmaaker 1970

As in Life drawing, in other areas battles were being fought. Colour fought across canvases, materials were wrestled with in sculpture and ceramics, inks on stone, plate and mesh in print studios and ideas were argued and discussed in sessions devoted to philosophy and history. All this against the background of another social revolution taking place in England as affluence grew and a consumer economy was born. Harold Wilson expanded access into higher education and music broke into daily consciousness as the radio and record player became more ubiquitous – remember the Dansette portable record player?

We (staff and students) worked and played hard. It was a memorable time I have difficulty in remembering….but will try in the next blog in this series.

This feels like half a dialogue but I don’t know what the other voice is saying. Indeed, there may be other voices who do not share a single position on the issues being debated. I find this confusing. What were the rules? What does the writer mean by academic (rational discourse or abstract pedantry or another meaning? The piece raises and abandons lots of interesting ideas.