My Verdun Triptych has now found a new home in a local public school, and there’s a story behind this dating back to the 1970’s. When I complete my degree course I was upset to be handed the application forms for a posts-graduate teaching course. This seemed like a vote of no-confidence by the college in my abilities as a painter, and I am pleased that I managed to deviate from this classroom profession in pursuing a life as a creative artist and designer.

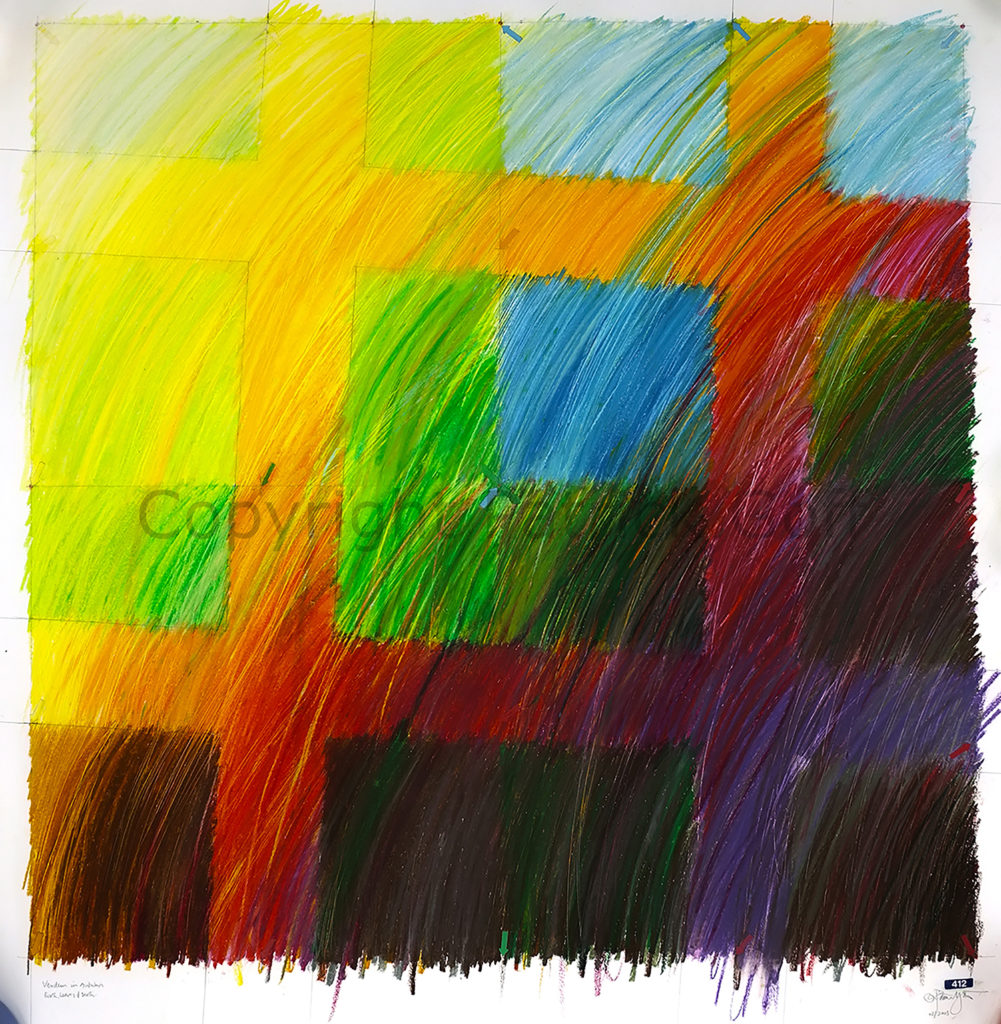

As part of the course I did teaching practice in a local school which has a bar in the staff room. Over the months teaching practice, I ran up a bar bill (of course), leaving without paying. Some months ago, chance sat me at a table in a gallery function opposite the current Principal of the school. My partner happily regaled him with the story, and I found myself offering the triptych to the school, to settle the outstanding debt. They came to see the pieces and were delighted to accept them, and they will hang in the history department as a reminder to their students of French sacrifice in WW1. I was asked to provide an explanation of how the works evolved.

I am fond of quoting English artist Bernard Cohen who talked of the balance between personal myth making and ritual. Myth making occurs through drawing and preparatory works. Here I explore the ideas, try them in small ways in sketchbooks, look at the possibilities and how they tie in with my underlying belief set. Some of this is at an unconscious, intuitive level, tapping into all those things that make us who we are – upbringing, DNA, religion, etc.. I like to work ideas out through drawings, works on paper, before committing to making a major statement which each canvas represents, which is why canvases are complex ritualised statements not ‘off the cuff’ responses to stimuli.

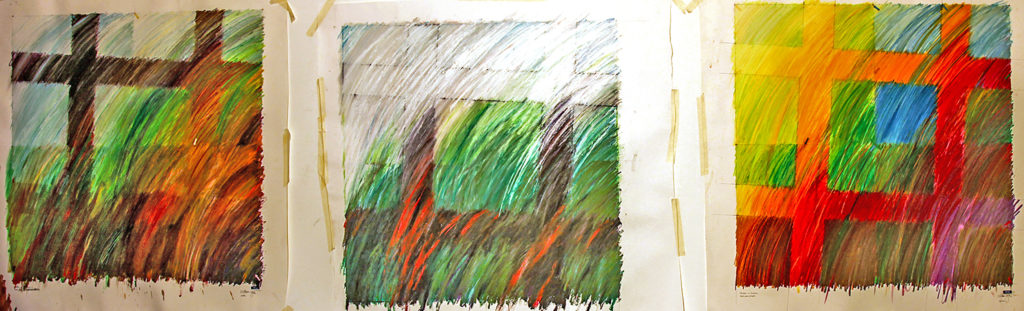

Drawing clarifies the vision pursued, sets up potentials for the ritualised realisation of the beliefs into the statements that are finished works – paintings, sculpture etc.. In the drawings, which some may consider more than just drawings, I freely explore the nature of the mark and colour relationships in contrast to the use of the brush in the making of paintings, where paint becomes a translation tool taking the things discovered into the formalised permanent statement. Of course, the process of ritualization raises more questions which leads in turn to more drawings, more myth making and then eventually another cathartic ritual event.

The influence of other artists makes each individual artist take myths forward into their own rituals, consciously or unconsciously. A kind of creative ‘stream of unconsciousness’ that links all art through time. This Jungian stream also pulls in areas such as environment and upbringing, even racial inheritance – in my case the Welsh side of me which brings the mysticism and dark moods that are apparently a characteristic of the Welsh.

During the seventies I was strongly influenced in my work by American realists such as Hopper, Wyeth and the Hyperrealists that were part of the ‘pop art’ movement but that was a culmination of admiration of much art from the past. Other influences reach back into the Renaissance, where many artists used mechanical means to construct their paintings. All became a part of my lexicon and I see their work reflected in the world around me (see previous blogs).

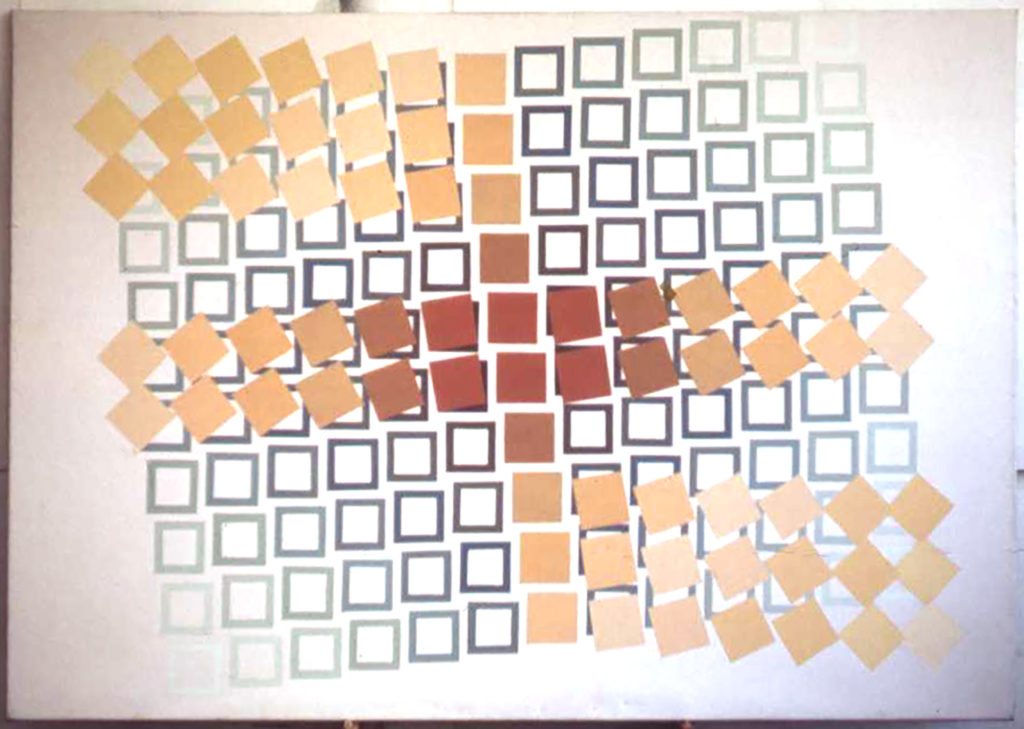

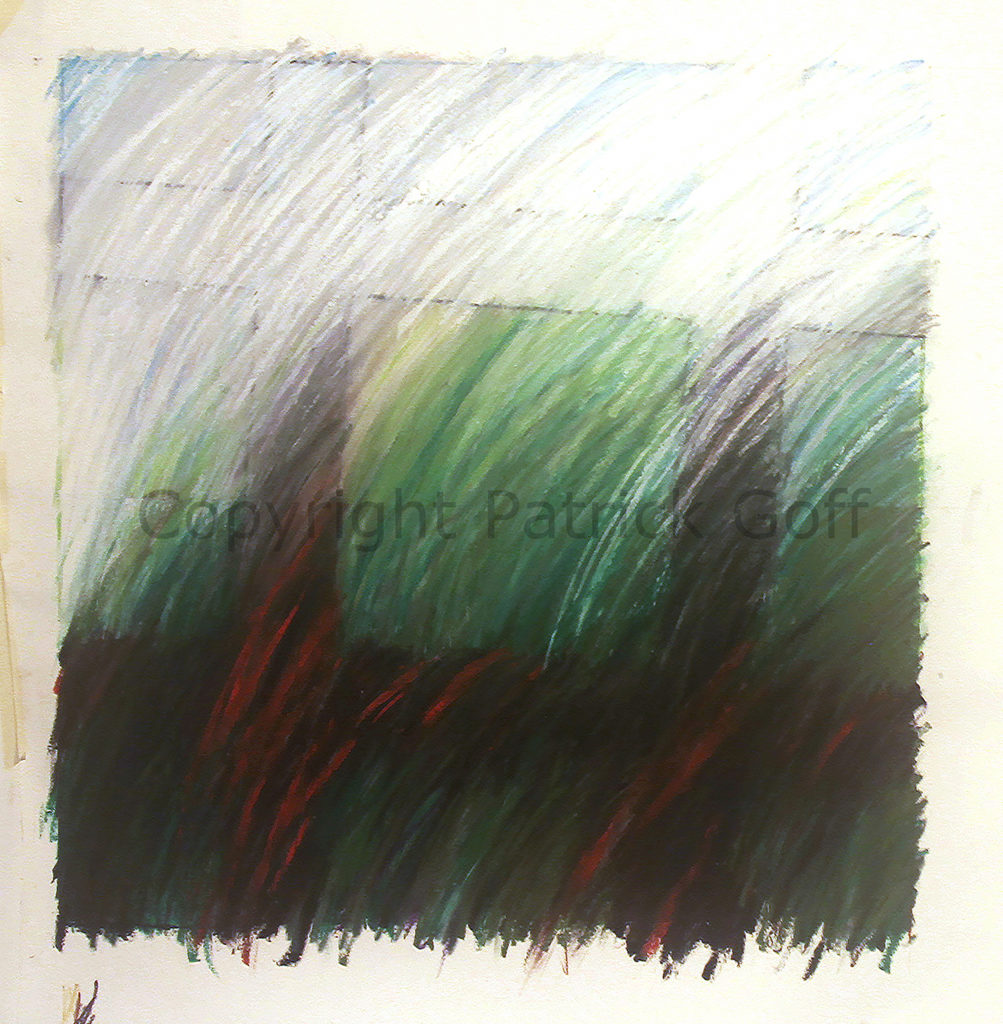

Smaller drawings would be enlarged using a grid structure, and I started to use a similar structure in my work, after using grids in construction of my early realist works. I started playing the grid’s rigidity against the random nature of the mark made by hand and arm holding a brush or pastel. If you like this was my homage to the past, mixing Renaissance with Abstract Expressionism, all in a structure that reflects the nature of our society and within a drawn outline that came from the world around me (my garden for example). The grid has come to represent our rule-based society, the structure which we kick against and which changes the way we live. Colour links to the real world we come from, moved and distorted by the rule of the grid. Alongside grid and colour the line drawing of the real remains intact.

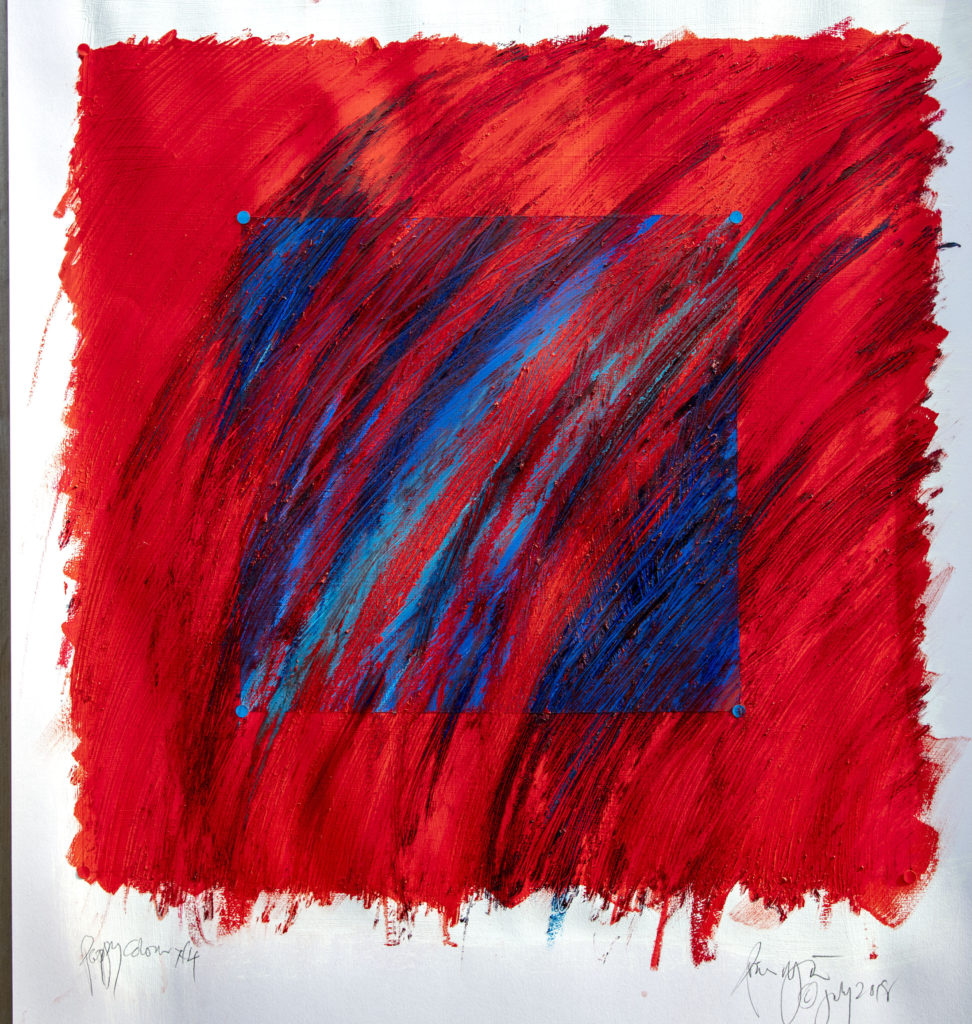

The grid in drawings becomes a single hollow square (grid within a grid) or a cross motif. The cross motif is a part of that grid, which fortuitously also echoed the simple cross marking French and German graveyards along the old front line of the First World War. Many of these graveyards mark the position of treatment areas for the wounded behind the front lines. I have a fascination with history (those who do not know history are said to repeat it) and as part of seeking ancestors killed in WW1, I made several visits to battlefields. One of these was to the killing ground that is Verdun, which had a huge impact on me.

Verdun reminds of the brevity and unpredictable endings of many of our lives for here in the longest battle of WW1 over 960,000 men became casualties, two thirds of them killed. Warriors are young, and for France the flower of a generation were killed. Much as towns like Accrington in England are said to have lost at least one man from every house, the deaths destroyed communities, many never recovering.

I made a triptych of drawings based in the colours from the images taken on a visit to this killing ground. The colours and marks also attempt to express the emotion that this area generates – the ground enriched with men’s blood over which the seasons flow generating new growth in forest and field. In Verdun’s ‘red forest’ birds still don’t sing, munitions still occasionally explode as they decay, sometimes releasing a cloud of poisonous gas, and people are deterred from entering by the hazards the brambles and leaves hide as well as fences and warning signs. These drawing became more than just an exploration growing to become emotive statements.

I took my 4×4 into the forest, carefully staying on the track passing trenches and turrets, wire and craters. The experience made the hair stand up on the back of my neck, the silence and stillness was evocative, deeply disturbing. The ground remains sacred to the French nation today, and despite the nearby National Ossuary holding recovered bodies of all combatant nations, there remain, as there do all along the front from the Belgian Coast to the Swiss border, bodies unrecovered. Verdun is the longest battle in European history, lasting 300 days and there are estimated to have been over 960,000 casualties.

Britain’s losses on the Somme were incurred, partially at least, in an effort to take pressure off the French army in its battle for national survival.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe;

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If you break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

by John McCrea, himself buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in Wimereux

I am delighted that my work will hang on a staircase in the history department, a reminder to the young of the debt they owe to the past. It is my second major installation on a staircase, as the Morley ‘Lupin’ mural, a representation of a tree of life, reaches across three floor of a staircase in that college.

Follow the studio on Facebook

You’ve really brought the killing fields at Verdun and the longest battle in modern history to life and tell it with great eloquence and clarity.

If it wasn’t for artists like you these devastating events and all those that sacrificed their lives for it would be tragically forgotten.

Really like the Verdun triptych – and the story!

Good to see the Tree of Life again on the blog – still see it many times a day and love it!