My local church is St. Leonards. It is in the centre of the town and for many forms the central focus of small-town life, a focus enhanced by its proximity to the railway station and both our doctor’s surgeries. It has a thriving congregation especially at Christmas when it overflows with worshippers. Two years ago, my partner saw a piece on Facebook about St. Leonard’s bell tower looking to recruit ringers who would join in ringing on 100th Remembrance Day of the end of World War 1. She pointed it out to me, and I joined 8 or 9 others in volunteering to join the Seaford Tower band. The ambition was to ring bells in both St. Leonard’s and Laughton towers on that Remembrance Sunday.

Why Laughton? It’s a sad story really. Charlie Brett was just 14 when he left Laughton, a village not far from here, for Australia. He was to return to the village in 1917 when convalescing from wounds received on the Western Front with the Australian artillery, visiting his family and the ancestral grave plots in Laughton church yard. He returned to his unit but never returned to Australia, being killed on the Western Front, his grave now lying in a small French village graveyard.

His name is recorded on the Laughton, Sussex,War memorial as he was a Brett cousin and grew up in Sussex. His family emigrated to Australia in 1911 and he subsequently joined the ANZACs as a Gunner in the 11th Australian Field Artillery Brigade. He was wounded in 1916 and recuperated in Brighton, Sussex, subsequently killed on 5th April 1918 aged 28 . He lies in a country churchyard at Frenchencourt.. His broken hearted parents returned to Sussex. I visited his grave in France with my partner to lay flowers

I was proud when I duly achieved competence enough to ring that Remembrance Day. I was one of over 3,000 ‘Ringing Remembers’ recruits who became ringers and over 2,000 of us still ring and are preparing to ring for the 75th Anniversary of VE Day. I now ring as often as I can, ringing on Tuesday practices and for Sunday services, but also joining practice sessions in other churches like Alfriston, the small village church known as the ‘Cathedral of the South Downs’. Ringing is a difficult skill to master, but ringers, the ‘Lords of the Ring’, are a welcoming group and tolerate my bungling and slowly growing competence. I am hooked on ringing, but it is also a family thing, partly because my uncle rang for over 40 years , but also because I come from a service background where respect for the bravery of those who fought and died to keep Britain free was very much a part of family life. I rang in Laughton in memory of my own late Air Force family as much as for Charlie Brett. Ringing has also played a part in my physical recovery from cancer, and it is 3 years ago today, March 15th 2017, that I was told I was clear of the dreaded disease, although treatment continues.

I am hooked on ringing, but it is also a family thing, partly because my uncle rang for over 40 years , but also because I come from a service background where respect for the bravery of those who fought and died to keep Britain free was very much a part of family life. I rang in Laughton in memory of my own late Air Force family as much as for Charlie Brett. Ringing has also played a part in my physical recovery from cancer, and it is 3 years ago today, March 15th 2017, that I was told I was clear of the dreaded disease, although treatment continues.

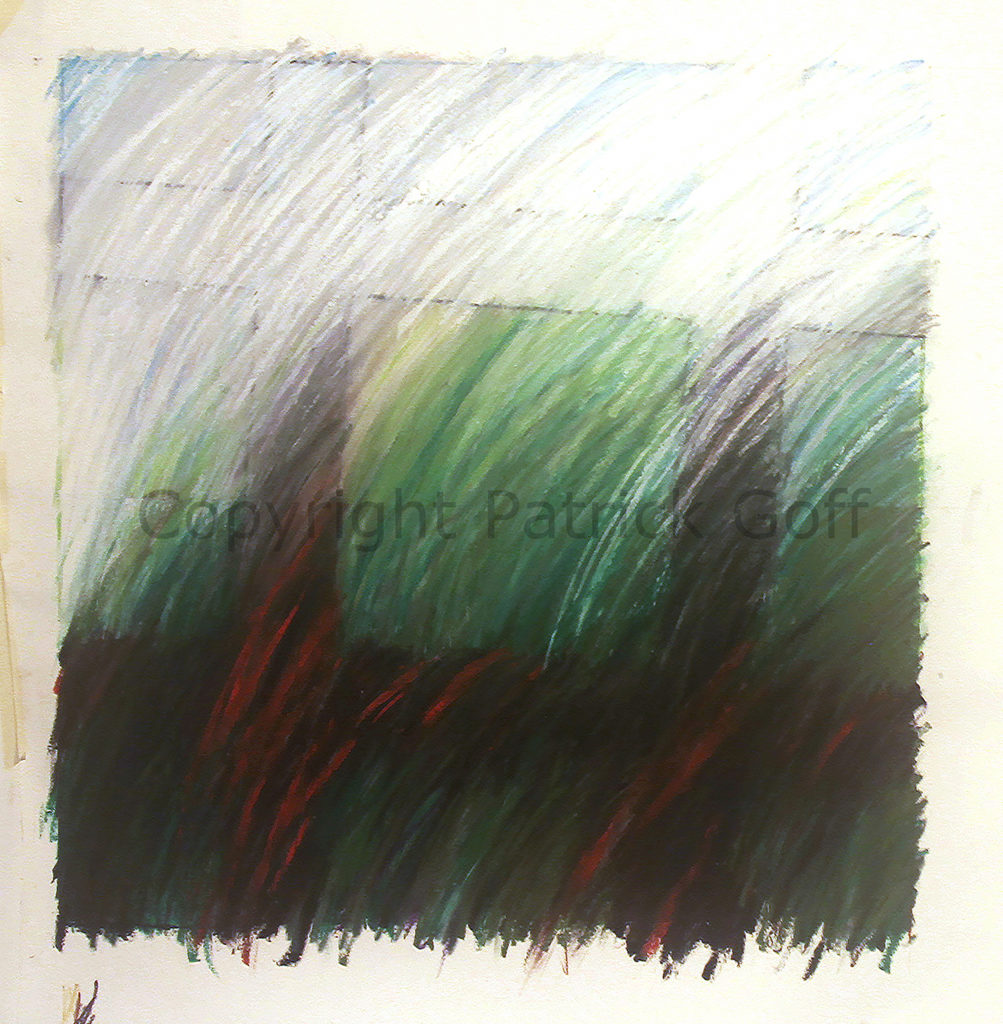

My art celebrates my life through colour and forms related to my environment. Whilst the paintings play with colour, my photography looks for patterns in life as well as reflecting the passage of time.  Remembrance became entangled with this in a triptych of works that were made in response to a visit to Verdun. The Battle of Verdun lasted 300 days and caused over 960 casualties in the longest most ferocious battle in Western Europe. I know our own losses on the Somme figure in the school curriculum, but many children do not know of Verdun. I was delighted when Eastbourne College, after coming to see the triptych in my Seaford studio during a local Art Wave event, took it to hang in the history department of the school this January. It will be a permanent reminder to English boys of the losses suffered by our French allies.

Remembrance became entangled with this in a triptych of works that were made in response to a visit to Verdun. The Battle of Verdun lasted 300 days and caused over 960 casualties in the longest most ferocious battle in Western Europe. I know our own losses on the Somme figure in the school curriculum, but many children do not know of Verdun. I was delighted when Eastbourne College, after coming to see the triptych in my Seaford studio during a local Art Wave event, took it to hang in the history department of the school this January. It will be a permanent reminder to English boys of the losses suffered by our French allies.

Verdun Triptych

Each of the drawings is 4 feet square, and the tritych looked stunning on the random flint wall in the gallery

The battle is reported to have claimed 960,000 lives over its 300 days. When the war ended a local priest began collecting the dead of both sides in a horse and cart, piling their bones into an Ossuary, containing over 130,000 anonymous soldiers. In 1920 his Bishop recognised his work and led a fundraising which resulted in the bodies being interred in a newly built National Ossuary.

People are still killed by unexploded munitions, including gas shells. Men describe the ground being saturated with corpses and parts of corpses. In one location a trench has been kept with the rifle barrels and bayonets projecting from the earth that fills it, each carried by a soldier buried when a shell explode and filled the trench in.

Verdun never fell. Troops were fed into the area along a single road now known and marked as a sacred way. The Germans nearly broke the French army, bringing about many desertions and a mutiny, but French forces held, and the Germans were equally bled. The famous British losses on the Somme were an attempt to relive the pressure on the French, and whilst losses by UK forces totalled millions in the war nowhere was action as continuous or as violent as the Battle of Verdun.

The experience of visiting was emotionally very difficult. My partner refuses to return to that part of France, although we both make pilgrimage to honour ancestors who died in Flanders. I found the symbolism of visiting the forest in the glorious colours of autumn and its contrast with the black of the gun turrets in the underground fortresses, the enormous cemeteries and the National Ossuary making a lasting impression that led to the creation over time of the three drawings, each symbolising a different season. The final one of Verdun in Winter came closest to capturing in colour and gesture my feelings about this place.

Verdun ranks alongside Auschwitz in my mind as a symbol of the horror man is capable of inflicting on man.

The Tower is now gearing up to ring in Remembrance again on the 75th Anniversary of VE Day, the end of WW2, in May. Hopefully I will be there then pulling straight, catching the sally properly, maybe even ringing ‘Plain Hunt’ successfully. I have taken photos of the ringing chamber in St. Leonards and other churches I have rung in and will one day introduce them into my artwork. The patterns we ring to are an aural version of the patterns I create in my art (to be seen next in Seaford’s Studio+Gallery, 21 Church Street Seaford in April, coronavirus permitting). The ringing craft is as much a celebration of life as my art, a celebration, a call to prayer and an ancient craft to enjoy.

We will ring on VE Day as a reminder of those, many of whom left from the dock in Newhaven, who gave their lives so that we could continue to live our lives free of European tyranny. I hope you enjoy the sound of the bells and will think of us who follow an ancient tradition (the oldest hanging bell in Sussex dates back to 1210) a craft that is quintessentially English, as we ring.

Both ringing and exhibiting were cancelled as a result of the panic over a virus