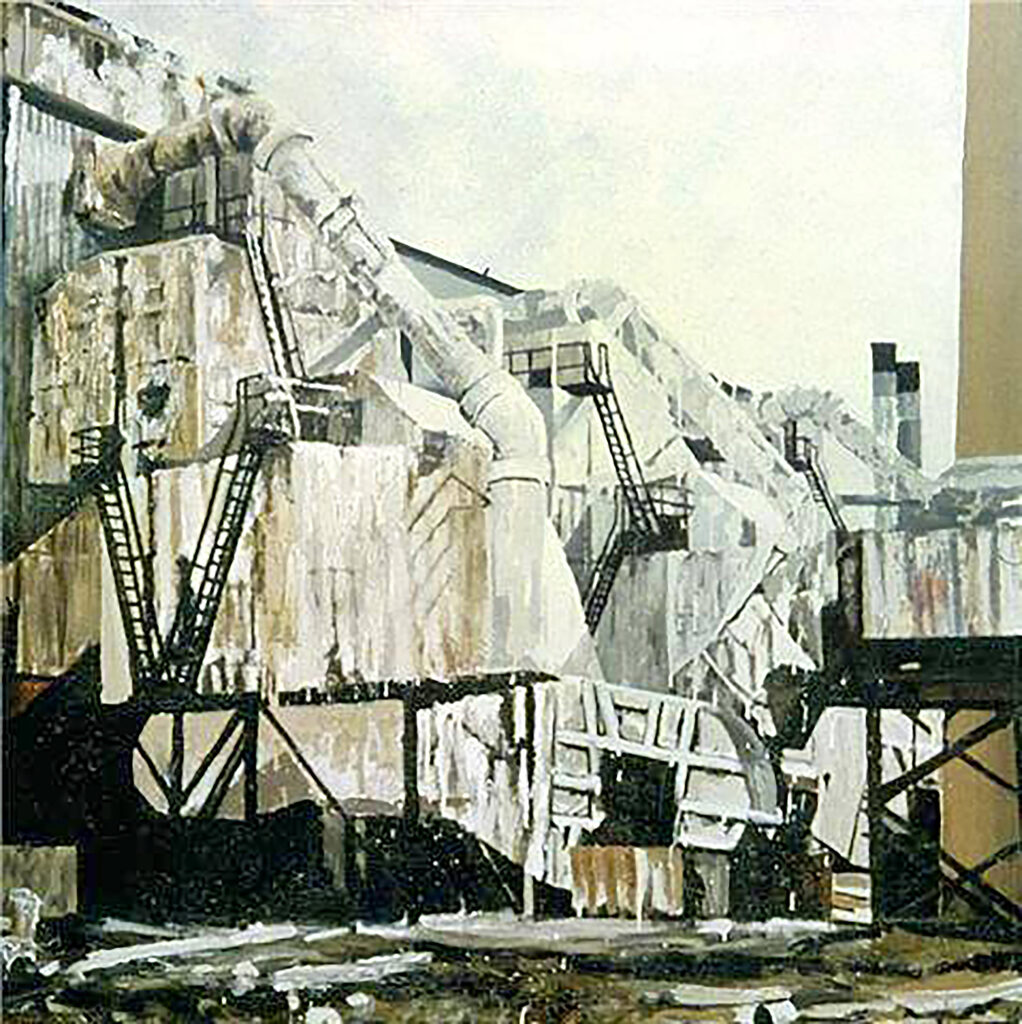

In my work documenting decay on the English South Coast I walk with a camera and record what I see with a view to taking it into the studio to process into paintings. This is a developmental path well known since the 19th century, flowering in the 20th in the work of many artists, but notably for me in the work of Edward Hopper and the underrated German artist Gerd Winner.

The German critic Luther Romain says of Gerd Winner and his work: “from the beginning Gerd Winner’s urban views have been as sharply attacked by social realists as by the solid middle class establishment. The former had already formulated a clear view of history which they would have been reluctant to re-examine, they could not see why anyone should fail to agree. Yet here was someone who still posed questions and set out armed with his camera to find out something about himself and his environment, which might be pieced together into an historical image. What seemed too loaded with content to the bourgeois critics, because it was what they most feared in art, was too aesthetic for the left, which was content to accept formulae and overlooked the connection between insight and sensibility”.

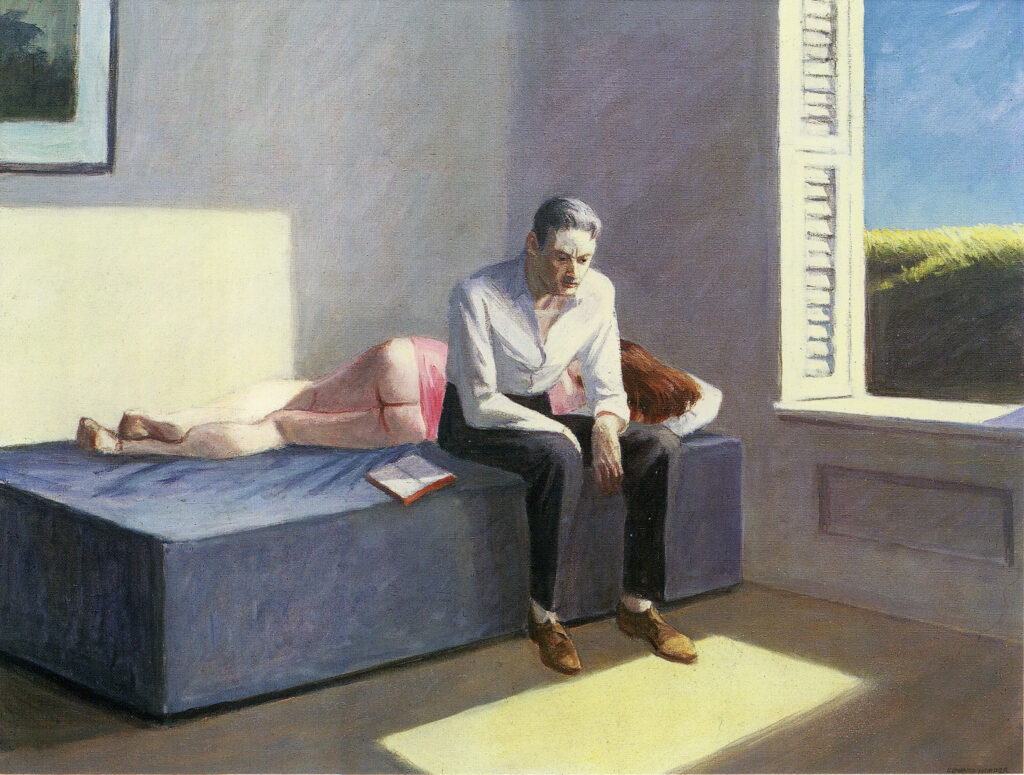

Gerd Winner was born in 1936, and Luther Romain starts his review of Winners work by placing him as a recorder of the collapsed German Society at the end of Second World War and its rebuilding. He sees Winner as one of a new generation of people who sought a new identity through art. This is why Winner, along with the American Edward Hopper (born in 1882), another artist whose work recorded the alienation of the individual from the cultural world he inhabited, remain two of the most influential artists in my work. Hopper recorded the alienation of the individual in US society at the time of the Wall Street collapse, a financial parallel for many Americans with the economic collapse of the German state. I know, I know, a broad-brush generalisation, causations were different but the two great underestimated artists both explored the alienation and isolation of the post disaster worlds they lived in. I see a parallel with my own recording of the collapse of post-Imperial British society. That my work is also an extension of using reality to express a view of the decay of a civilization, mirrors the working approach of the two masters.

Like Winner and Hopper (for he too took photographic images as he travelled, for use in his work) I set out armed with a camera to find out something about myself and my environment to reflect the society I see and live in. Winner in his work with the late Chris Prater and other screenprinters, moved closer to abstracting from his photographs than Hopper, he was of a much later generation with different technologies available. I too have pushed the relationship between the reality captured in my photographs and the resulting paintings and giclée prints – giclée having largely replaced screenprint, both techniques relying on laying down dots of ink on a receptive surface, but digital technology enabling a faster development of the ideas for my generation. It is this growth in technology that pushes me to emphasise the mark of the human hand, the autograph, in making paintings, in opposition to the depersonalisation of images made by machine, whilst for Winner the hero was his printer, his mechanic.

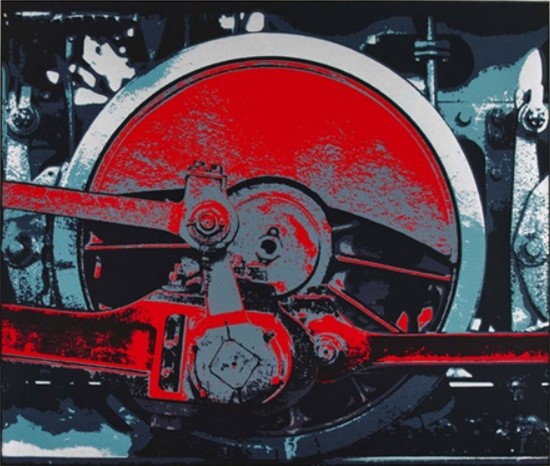

Screenprint investigating the mesh, using curtain netting, its coarseness creating a pointillist quality in the ink laydown. Part of my 1970’s Ph.D research

In a note to me from May 1980, Winner says the following: “I soon discovered grids and grainy textures and began to incorporate them into my work. Adding such structures to the tonal and flat areas of the composition permitted a more subtle approach, directly combining the possibilities offered by photographic methods and the effects obtained through the tone separation process is as well as collage methods of addition and subtraction. The more thoroughly I explored screen printing the more I came to realise that in view of the many problems of crafting technique posed by this new process a painter needed to partner a printer, who, parallel to my own artistic concerns would continually research technique. The printer must become a partner he and his technical expertise must become part of the creative process and his readiness to cooperate is essential”. He continues “the artist should ideally be a printer himself and the printer an artist”. This is true of such outstanding printers as Chris Prater and others who have not only had a decisive influence on screen printing as an art form but have introduced artists to the process.

Tilson ‘New York Decals’. first of edition of ten screen prints, now in the collection of the Towner Eastbourne. Tilson another artist introduced to the medium by the ICA programme

It should also be noted that the foundation of the Tate Gallery’s collection of prints was the Institute of Contemporary Arts which in the 1960s encouraged many artists to experiment with silkscreen including people like Hockney, Hilton, Heath, Caulfield, Jones and many others. They eventually amassed over 1,200 screen prints by UK artists who they paid to play with this new medium and this was donated to the Tate by the ICA and formed the basis of the national collection of Prints. In a conversation I had with Adrian Heath, he confirmed his dislike of the process but for some like Patrick Caulfield, the ICA programme was revelatory.

Winner adds: “this collaboration between artist and printer takes up a tradition that goes back to the beginnings of printing as a graphic art form the revival of printmaking in the early 1960s in which screen printing played a major role made it once again financially possible for artists to work in partnership with the printer”. It was during the 70’s I began my own collecting of prints, now forming the 30+ collection of predominantly screenprints I donated to Eastbourne’s Towner Gallery.

As a coda to this history I would add that my own cancer can be related to the solvents used in screen printing and many of the star printers including Chris and Rose Prater died of related cancers because of the nature of the inks and solvents used in the process.

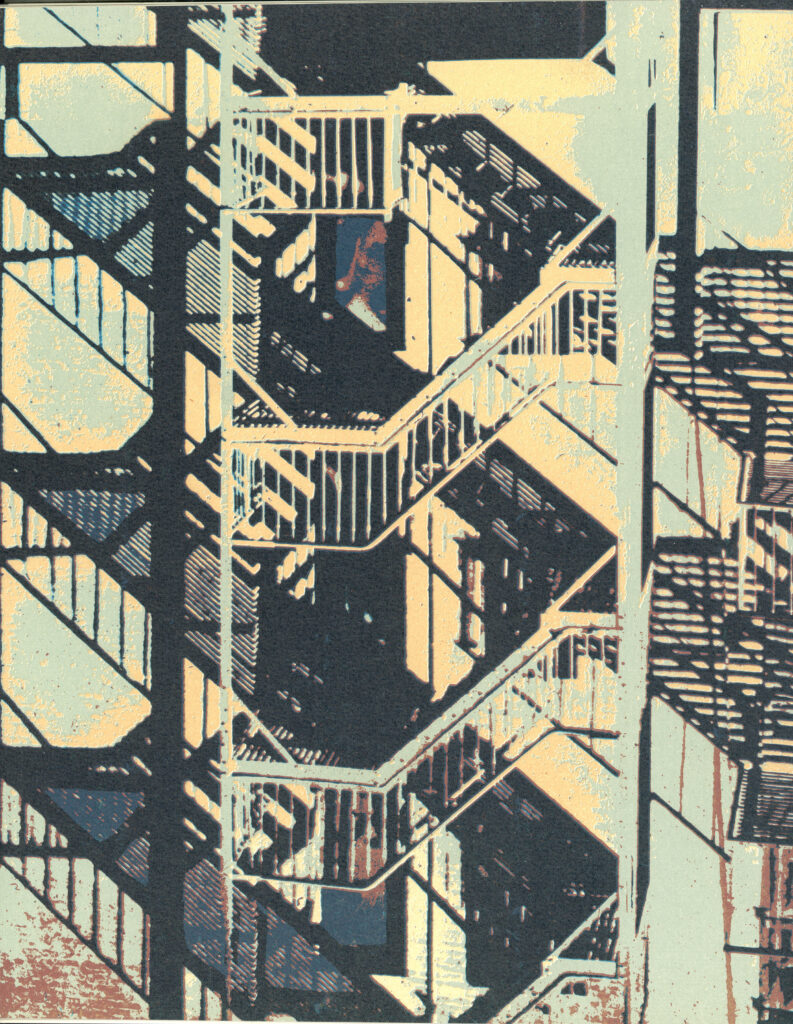

Print Image one of four bound into a limited edition Winner exhibition catalogue (this numbered 1083) now in my library

Whilst screen prints continue to be produced they’re now in the realms of etching and lithography as a craft activity separated from their commercial use. Their commercial work is what I did as a printer in the 1970s and 80s when I produced such wonderful items as signs to the side of Huddersfield buses and plastic pub signs. For an artist the need for a collaboration with a printer is much more limited as it is possible to buy high quality digital printers which enable the production of large-scale prints directly from manipulated photographs or scanned artwork.

In my conversations with patrons and visitors to my studio I have been surprised by how many times the conversation strays into the meanings of paintings in those same areas where Luther Romain says in Gerd Winner’s works were sharply attacked by social realists or were too loaded with content for bourgeois critics. The conversations frequently result in denial of the reality as I, the artist, sees it and cause a quick change of subject for people who don’t want to see their comfortable reality challenged by art which should not have meaning which could impact on their lives. As one man pointed out to me, prophets are not honoured.

This denial of course completely at odds with the impact of art through history. We don’t have to go back to artists painting religious icons or the Sistine ceiling to understand the impact that art has on our political process. It’s interesting that in the context of Winners work that before the war the German establishment in the form of Adolf Hitler considered the impact of art very dangerous and labelled much of it ‘decadent’ and as such hid it away or destroyed it (much as the Arts Council ‘loses’ work today). In this respect the ‘right wing’ if I can use a lazy contemporary term for Hitler and his henchman was just as bad has the ‘left wing’, in the form of Stalin and his socialists. To see the illusion of difference of these terms imagine a piece of string, one end the ‘extreme right’, the other the ‘extreme left’. Make your piece of string into a circle and the extremes are next to each other, useless labels denoting monstrous beliefs surprisingly similar in suppression of freedom.

Artists were used by the communists on agit prop trains and in public discourse to try to pull on board the population in support of the Russian Revolution. Those artists who disagreed were quietly taken behind a barn and received thanks in the form of a bullet to the head. In my piece on the danger of subsidised art I talk about the values of the state being imposed on what is considered good art. Could it be that in our so-called liberal societies the power of guilt used by Green Party and socialist parties alike has so deformed the value systems of the art establishment that they are no longer able to hold objective views and justify what is good against what is not good? Or is the argument about the debasement of all language, not just artistic or critical language? Is artistic language, the criticism that art attracts, a victim of the same corruption of language that allows men to pretend they are women? Treacherous ground underfoot here, but too many exhibitions recently contain poor work produced in social programmes designed to satisfy the political needs of their funder such as the Arts Council.

Using recognisable image formats can provide a ‘doorway’ into understanding for our visually saturated but largely visually illiterate society. A society so poorly educated visually is now in grave danger of suffering increased fraud because AI will allow the creation of alternative realities for advertisers and governments alike and the public lack the skills to differentiate between real and artificial. The power of a Winner, or a Hopper is the recognition by the viewer of the realities portrayed by the artist being extensions of images of a real world. Our education systems have for years failed to develop visual acuity as real life has come increasingly to depend on screens and pictures to convey information rather than the written word. Our classically educated elites and middle classes have wallowed in their visual naivety and will be consumed by their own ignorance.

In creating art colleges in the 19th century, the much-maligned Victorians recognised that the alternative views of reality were essential to the continued development of both society and industry. Both Hopper and Winner look at the development of industry and society with their artists eyes, as I do whilst I try to reflect its decay. Other artists too tackle these themes but unlike previous generation where art may have been a major element of visual messaging, the growth, or more appropriately perhaps, the explosion, of visual messaging through screens we now access on the move, at work or in the office, has rendered making artworks ‘old fashioned’, messages now being propagated through film and television, and contemplative imagery and the beauty of an artwork etc. is now consumed by momentary flickering electronic propaganda.

I will continue to gain much pleasure and understanding from the slow contemplation of a single image, to see the mark of its maker, and to try to unpick its meaning.

I for one will continue, as the fool on the hill, to watch the world go around, and see the universe in a flower. That is where the magic of great art lies.

Recent Comments