I am a painter not a sculptor. We think differently. I did work as a designer of interiors and products – chairs, lights, carpets and commissioned sculpture, so I do have experience of working in the three dimensions a sculptor works in, not just two, although my work plays with the 4th dimension too. Hepworth’s time was a universe apart from the environment in which artists work today, not that that has changed the dominance of the art world by the same art establishment that dominated it in the 1920’s when she emerged from the RCA.

Born 1903 as a young artist she grew up at a time dominated by revolution and war, and her English art inheritance includes contemporaries such as Wyndham Lewis and Nash, whilst the impact of continental art forms was also sweeping home. Monumental sculpture responded to the first World War with memorial pieces – not just with works like the Cenotaph for formal mourning but also stunningly moving pieces of emotive sculpture like those of Kathy Kollwitz. In the in mid-twenties, she immersed herself in the traditions of sculpture with a stay in Rome and her links with the British School there helped start her career.

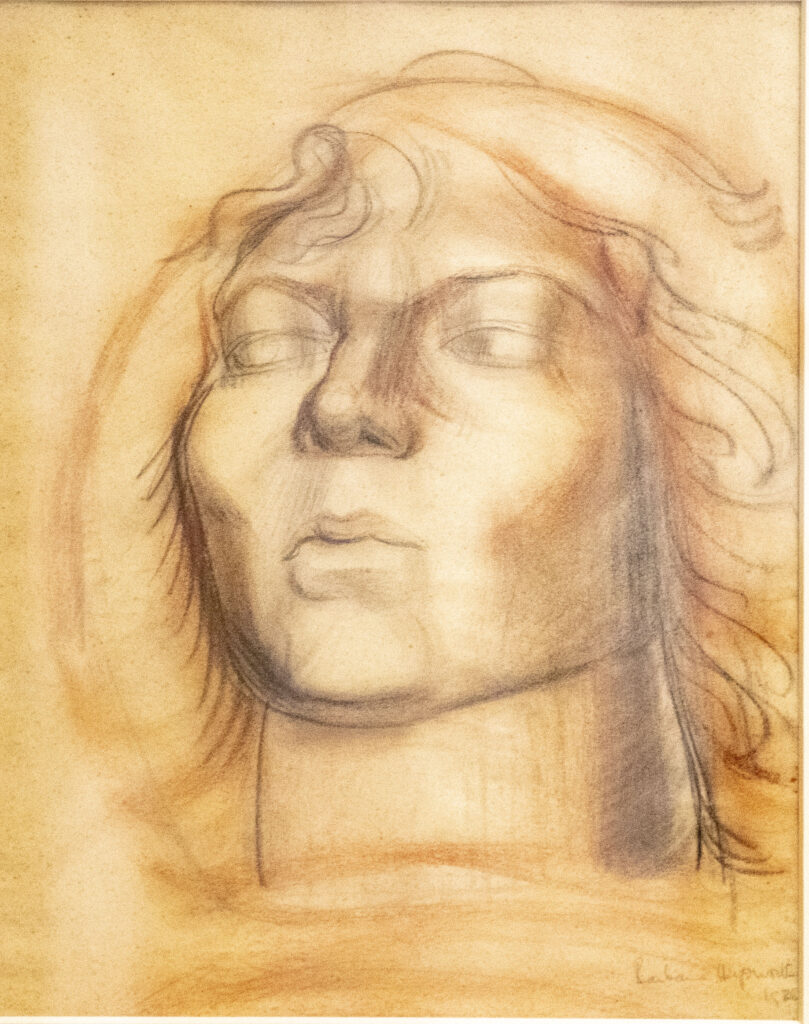

Her early drawings show the sculptors eye for mass, but a major turning point for her came when she visited Brancusi in his studio with Ben Nicholson (whose influence is strongly present in her later drawings). They obviously engaged and had conversations as she showed him photographs of her own work (cheeky?) but she says “in Brancusi’s studio I encountered the miraculous feeling of eternity mixed with beloved stone and stone dust” and goes on that the studio “filled me with a sense of humility hitherto unknown to me”. For Hepworth it was “a special revelation to see this work which belonged to the living joy of spontaneous, active and elemental forms” (quoted by Herbert Read)

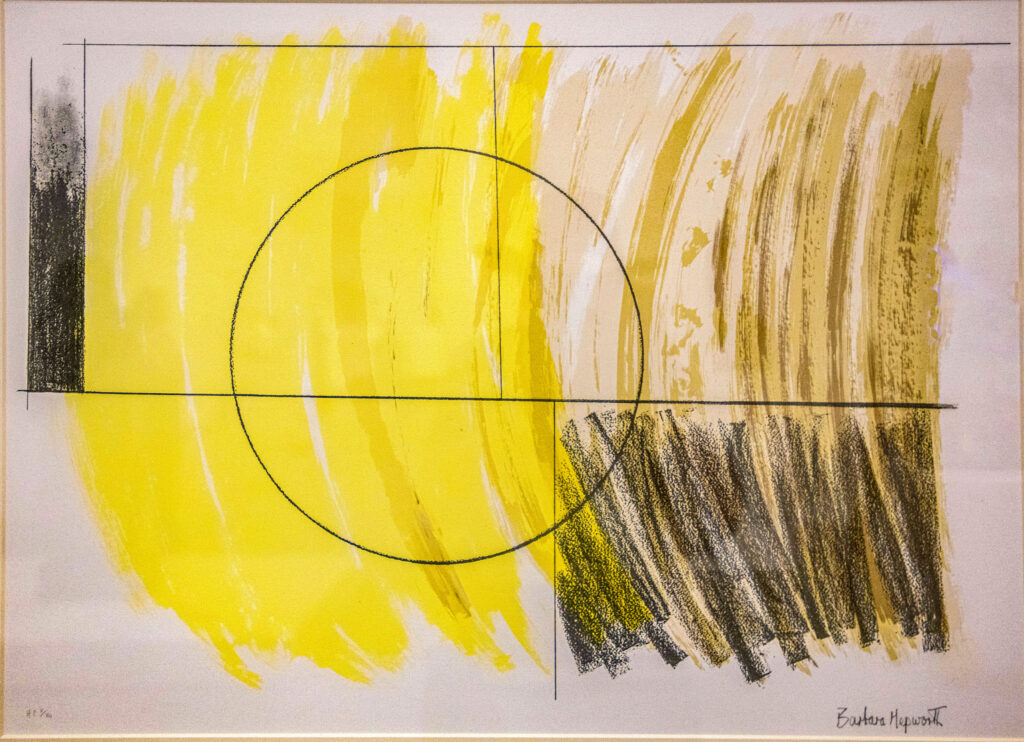

The show sprinkles works that clearly show the influences on her – not just of Brancusi, but also the delicate wire pieces reflecting the influence of refugees from Russia and the Bauhaus such as Moholy-Nagy and Naum Gabo. Hepworth’s own pieces are clearly a product of that deep well most artists feel, where their soul catches the flow of art through time and produces from a deep well of human emotion and experience, a true link to a world of beauty that exists timelessly. Some give this to religion, and it is something from the soul, maybe the artist is a passageway for the beauty contained in, for the sculptor, the materials of the natural world – timber, stone as for the painter in the texture and colour of paint.

Herbert Read says of the influence of Brancusi “she lacks Brancusi’s heritage of folklore myths — instead she has gone directly to nature, to crystals and shells, to rocks and the form-weaving sea”. This was a time when widespread knowledge of psychology was being absorbed into everyday thinking, and the role of the collective unconscious and Read says there is a depth, “an element in Henry Moore’s work, not present in Hepworth, which comes from a deeper level of unconscious – the Shadow as Jung called it”.

For me Hepworth’s sculpture doesn’t challenge in the way a Caro might, it seduces with its forms and rewards contemplation. Some of the smaller pieces yearn to be seized and smuggled home to be enjoyed in quiet solitude, their beauty restorative and rewarding contemplation, and it is these ‘domestic’ pieces that I particularly enjoy in the exhibition. The sculptress’s handling of wood and her use of colour on the forms being particularly seductive. It is good to see how wood carries so much beyond the sculptor, its grain referring to its life as a tree and the permanence of the material secondary to its beauty – something writ large in a previous beautiful sculpture show at the Towner, the Nash.

The show is beautifully displayed in the Towner. I will go back again (although I find the drawings disappointing). Art is a powerful influence on society as much as society and man influences artists. Can it have that influence today you may ask, in a world of electronics. Of course, it can be seen as even more powerful in the fakery of electronic imagery and the fake row over gender description can be argued started with Duchamp’s urinal or even accelerated with Michael Craig-Martin’s glass of water as an oak tree from the Rowan Gallery in 1974 “What I’ve done is to change a glass or water into a full grown oak tree without altering the accidents of the glass of water”. I recommend you read the interview, quoted in ‘Towards Another Picture” by the Midland Group in 1977 and see the difference between conceptual and material, and understand the difference between gender and sex.

Hepworth was in tune with the material world, with “the simplicity and dignity of the artist”. In tune with “soaring forms and still quiet forms, all in a state of perfection in purpose and loving execution”. Her quiet ‘Single Form Memorial’ from 1961/2, cast in bronze was chosen to stand outside the UN as a memorial to those who lost their lives when mediating the war in the Congo. That it both works as the beautifully carved iteration in the show and as a mammoth bronze almost discreetly displayed in front of the UN building in New York is a clear example of her achievement as a leading sculptor of the 20th century British art world.

Barbara Hepworth: Art and Life is at the Towner Eastbourne until 3rd September.

The full text of the Michael Craig-Martin interview at Rowan Gallery in 1974, Craig Martin

published in ‘Towards Another Picture’, Midland Group, Nottingham in 1977

Recent Comments