The silo, disused since 1990, stands as a monument to the industrial past of Cape Town, at one time the tallest building in South Africa, now given new life through the transformation and forming the centrepiece of a series of silo buildings housing new restaurants and offices, extending the existing successful V&A Waterfront towards the Cruise arrivals port. The Waterfront is one of the most successful, exciting and dynamic regeneration projects I have seen anywhere and boasts of being the safest place in South Africa.

The Zeitz galleries and the atrium space at the centre of the museum have been carved from the silos’ dense cellular structure of forty-two tubes that packed the building. The development includes 6,000 square metres of exhibition space in 80 galleries, a rooftop sculpture garden, state of the art storage and conservation areas, a bookshop, a restaurant, bar, and reading rooms.

Six floors top off the building containing 28 bedrooms and public areas of the Silo Hotel with prices advertised as starting at over 19,000 ZAR (£1,100 sterling at the rate as I write this) per room per night, emphasising the enormous gulf between the riches evident in the Cape and the large numbers who still live in the unsanitary shacks and shanties despite over 25 years of African National Congress rule.

The conversion of the redundant grain silo by London’s Heatherwick Studio is a tour de force, turning the 14 tubes of the grain silos into a unified set of spaces to display the collection of African Art. Initially the collection is built around the Zeitz collection, but the Museum is eager to encourage other collectors of African arts to contribute to aid growing the collection. I hope that it will exercise an African eye, not a white middle or upper-class eye, in determining what will be added to the collection as there is a need to balance the cultural history of Boer and Brit with a strong dose of African aesthetics. The early promise is good, with a heavy emphasis on the art of protest possibly leaving some visitors uncomfortable with the wry observations on slavery and the corruption endemic in many African states.

The entrance is breath taking, the large piece domination the entrance hall quickly becoming known as the ‘Dementor’. Entry price is 180ZAR, about £11 to a tourist but a large chunk of a weekly wage to a local, so much of the audience on my visit was of pale white folk, the lack of suntan marking probably largely tourist roots. This is a pity as the museum has much to say about the African peoples struggles through its art works, and I hope that like Eastbourne’s Towner Gallery it will have a strong interactive programme with local schools to bring in children and enthuse them about their own artistic cultural roots. Zeitz does offer free entry to African citizens between 10a.m. an 1p.m. on a Wednesday, but this is not much use to the working man.

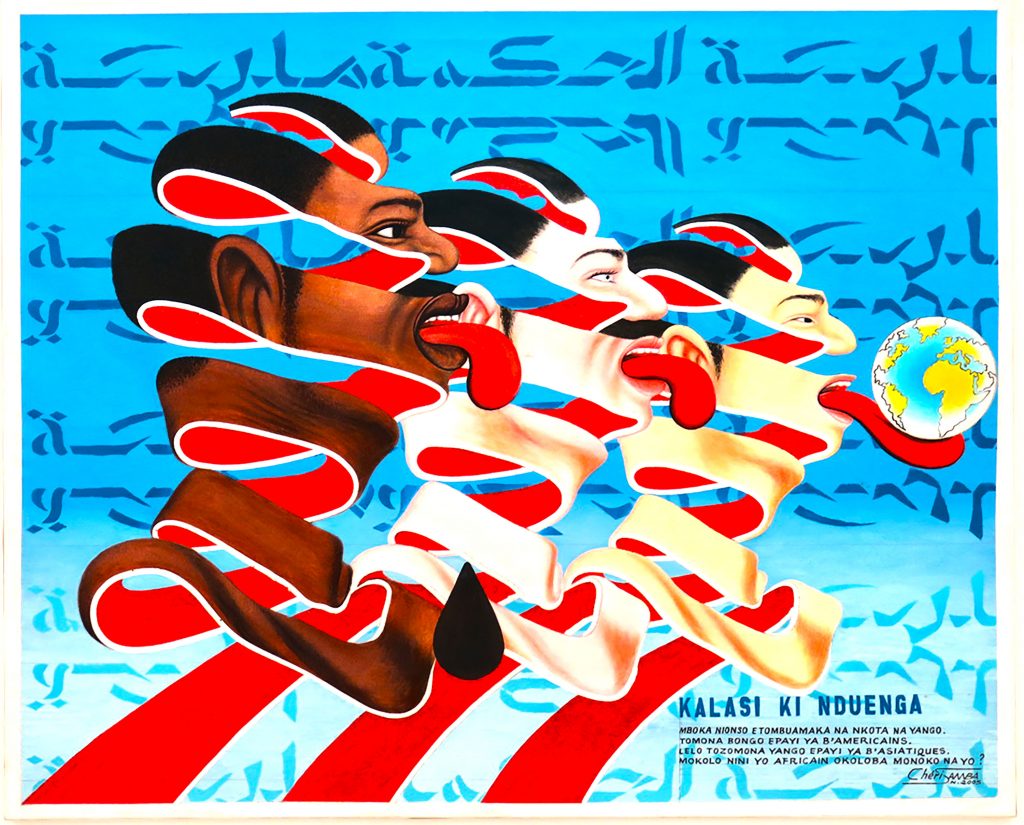

I found the work aroused in me emotions I experience when visiting galleries elsewhere – dislike for some of the work, total awe at other pieces. Some show the traditions of satire and protest as Hogarth and Gilray did in earlier centuries in England, some speak to the beauty of people in much that way many artists do, other pieces exploit techniques that are a product of environment and available materials.

The galleries are well laid out, the plan form making it easy to start at the top and stroll down the building through the various spaces. Inevitably the collection is reflective of the collector as much as the artists, but the work was all strong despite my dislike of some of its understandable monomania, protest becoming repetitious after a while, and my preference is for art that seeks out the beauty in our world. So much art now seems polemical, posturing overtly politically with no attempt at subtlety nor drawing a viewer in through the art to discreetly cosh them with a message – no, now the art influence seems to come more from the shrieking of the advertising world, so impact is all important, contemplation rarely reveals further depth.

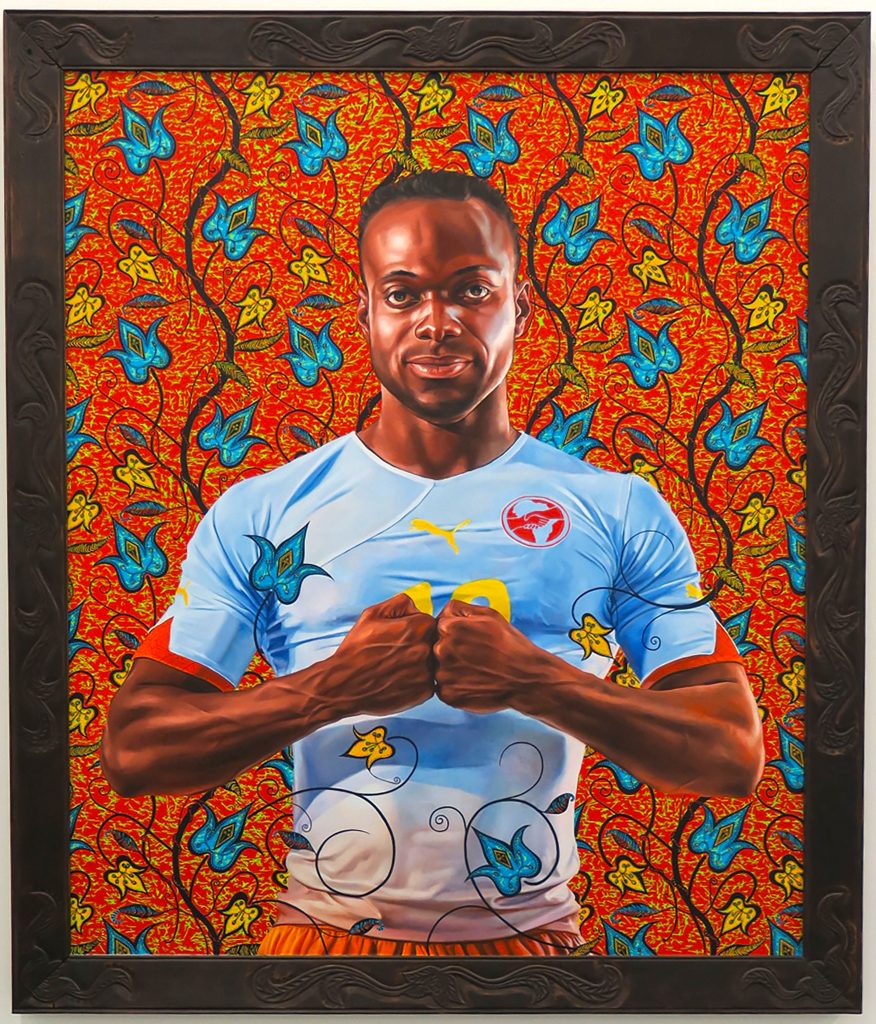

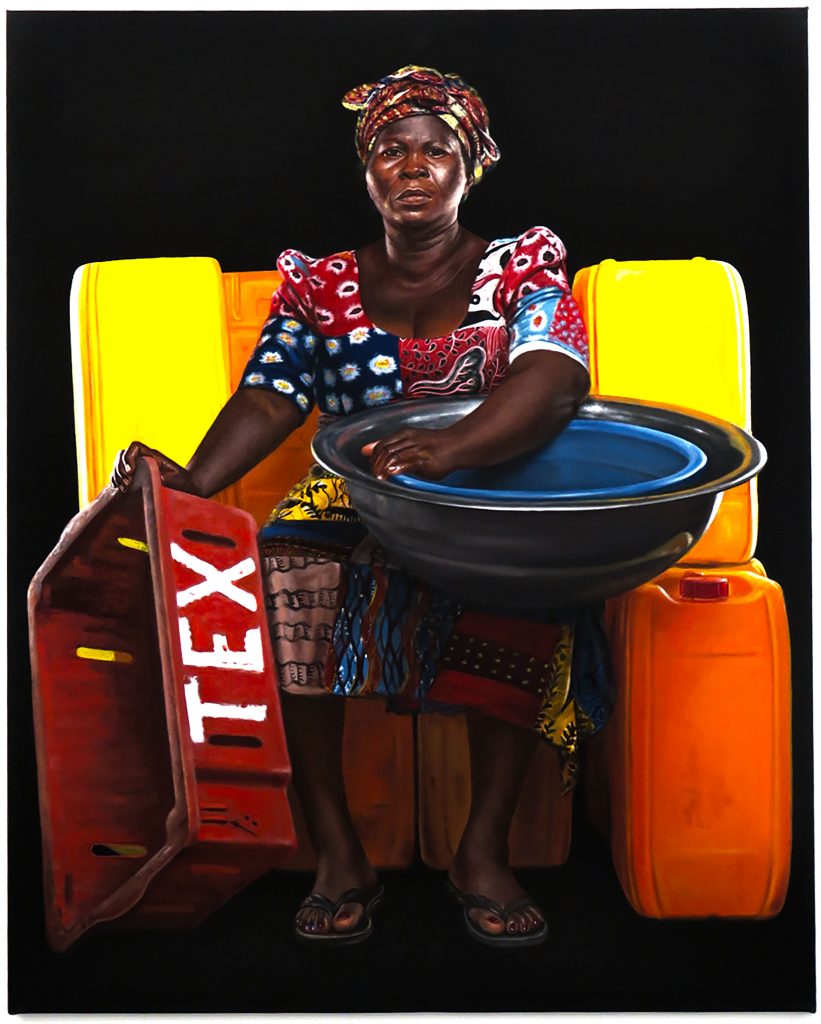

That said, there is beauty to be seen, and here I have picked out a few that I liked, that I feel do reward contemplation. Bringing an educated art eye to looking, revealing depths and beauty in surface and colour, grace and dignity, in short something of the beauty of our world, feeding my soul as well as my mind, something all great art should do.

The building is a true cathedral devoted to art. The spaces are well planned and brilliantly executed, although the restaurant was closed when I visited, and the rooftop sculpture court amazingly thinly stocked given the historic strength of African sculpture – again maybe this is an area another donor will compensate for the Zeitz collections focus on 2d rather than 3d. The galleries were well curated, a subject of discussion and debate between myself and my companions as we discussed the worth of curators, this new layer inserted between artists and the public

If you are a designer, you will enjoy Heatherwick’s spatial planning (I imaging the studio had much fun slicing toilet rolls in modelling) and the drama of the interiors. If you are in to art, then the exhibitions will be thought provoking and will leave you wanting to revisit, which I will certainly do next time I am in Cape Town. The Museum left me wanting to see more and wanting to debate the contents seriously, which every good gallery should do.

Recent Comments