“This happy band of men, this little world

This precious stone set in silver sea

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm,

This England”

Shakespeare’s Richard II

“The centuries have left their enduring mark on the land and its people in the form of age old traditions, a deep inbred loyalty and a wholesome respect for law and order” says my ‘Book of Knowledge’ from 1955. It goes on “Go into the little village church ivied and lichened grey with years. History stares at you from the escutcheon nailed above the door, the stone seats beside the entrance had provided rest for generations of tired folk. The bells, with ropes dangling from the rafters of the tower, have toiled for generation after generation of true Englishmen, perhaps gave a warning of the Spaniards coming in their great Armada. The recess beside the altar speaks eloquently of a primitive rite and a more ancient church. The brasses upon the chancel floor show Knights clad in armour such as the Crusaders wore and dames in stately steeple hats. Upon the walls a Tudor squire and his lady beruffed in starched magnificence, kneel to pray surrounded by their children. From this pulpit all the winds of theological opinion have blown since the Reformation. As for the churchyard, the bones of village fathers lie deep, pressed heavily layer upon layer, one rich mould of human soil.”

I had a couple of shows in Brighton which featured paintings that were largely based on photographs of the architecture of the town. The second show started to breakdown that realistic painting approach into more abstract forms partly because selling representational paintings was just too easy: they went, they sold, and I was suspicious that they were not saying anything that matters but were just pretty pictures. I started to look inwards and make things a little bit more representative I suppose of what my thinking was. As a youngster life’s very straightforward – find somewhere to live, find a partner to share your life with, onwards and upwards.

As a part of the changes in my life I started to look at ways of breaking the image up, of walking a line between abstraction and reality in representation, something I continue to do. I was looking for something which would say something about British society, about my country, the world now and where I live that went beyond just the representational. That Book of Knowledge quoted above had obviously taken a deep hold on the young me.

In my efforts to get away from straightforward representation I abdicated responsibility for the imagery choosing to use images from a children’s colouring book. Playing with them and how I could deconstruct the colour from the image, using the grid and chess moves started to play the major role in structuring the paintings. It was one of these that was bought by the Arts Council in its outrigger organisation of North West Arts back in the 1970s. I was visited by a remarkable lady called Helen Kapp, who made the purchase of their behalf.

Having sorted out some of the problems of what I wanted to say in the paintings I then started to reintroduce my own imagery using for example kitchen taps, flowers that I had grown in my own garden (a garden I created in a wasteland) and simple domestic images such as teapot etc… I also started about this time research degree at Lancaster University and so I was exploring my deconstruction of the image through printmaking as well as painting. The use of the grid continued and developed and I began to see each picture in itself as about the grid. The grid originates as an artist’s technique way, way, back beyond and before the Renaissance when it was used to squaring up small images to paint onto large walls. History grabbing at me again.

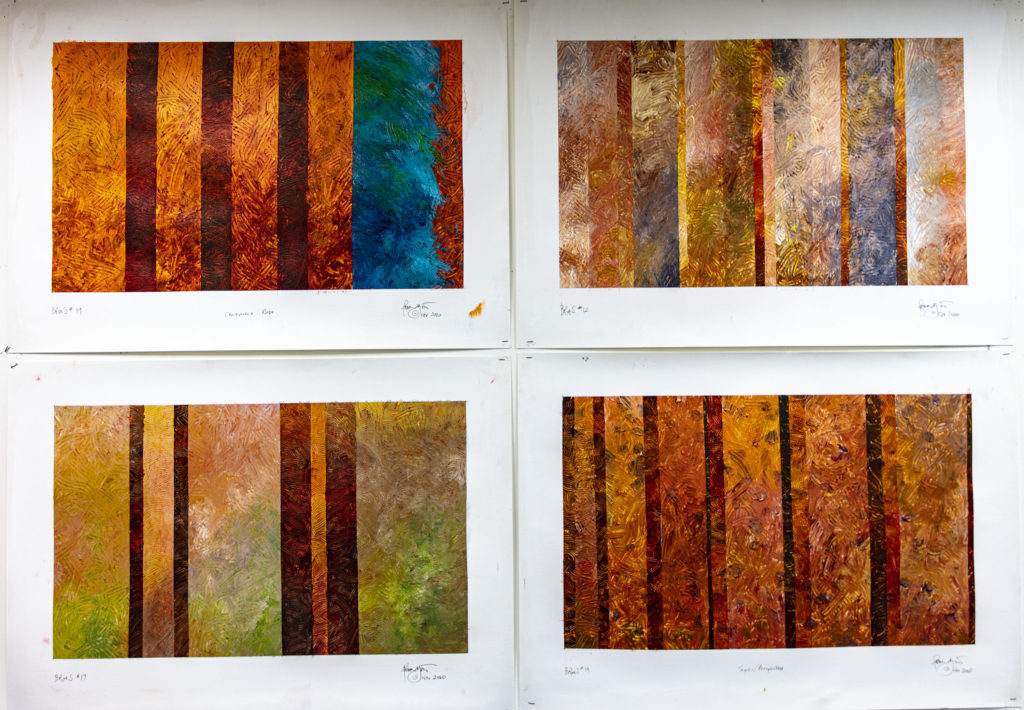

In those earlier times the grid was subsumed into the painting, it vanished, it was part of the approach much as primer is and in a way this reflects the power systems of the period. To most people those who ruled were invisible except for the occasional fist, whilst the imagery itself was a useful tool for communication used by the powerful partly to control the general population. For me the grid as a control mechanism needed to be seen for what it was: something that was imposed over our lives by our law-makers and which distorted the colour of those lives and so I produced a whole series of paintings over a number of years in which the grid was used as a tool to disintegrate colour from images made from my world.

These paintings were very successful, sold very well (if that’s a measure of success) and I had many exhibitions from them. I used the technique in submissions that took my work into shows such as the ‘Flags and other Projects’ at the Festival Hall sponsored by the Arts Council again. The source of imagery came from my life and as I moved house and developed gardens so I used what I grew, plants that I had a relationship with intimately, in making the imagery. The colour of the plants and their flowers were broken away, dislocated by the grid. I also worked in oil pastels and paint on paper to explore how I was putting colour down, looking at edge, stability etc…

The colour was detached from the imagery, but the imagery was still there and recognisable much as our lives are still there, recognisable despite the rules and regulations that govern them. As society has become more complex so those rules have become more complex till they’ve reached the point where they know they no longer hold any truth for many of us, and where they often conflict one with another. We also get politicians now who can make all sorts of promises before they’re elected which they can then completely ignore. In the case of the current government, they proposed a programme which attracted a majority of 80 after a period of convergence between the two main political parties had given us governments with small margins of power. Unfortunately, having used these promises to gain this large majority they then promptly dumped the leaders who taken them into power and turned their backs on the promises. In the grid of laws that we now have, control is being intensified. Over time it has become more powerful, a power that was tested to see how we could be locked in our homes. The grid will develop to include methods to control how and what we spend our money on through so-called digital cash. The politicians who now govern us no longer have a mandate but grasp and wield their despotic power. Meanwhile we still suffer the results of earlier decisions which disrupted the social grid turning our country into a province of a larger power briefly.

This larger power decided that between all its member states it should have no borders. For our country, the most overcrowded major country in Europe, this has been the final straw in breaking the bonds holding together our society and our culture. Increasing dissent in the cities; increasing violence in the cities; increasing detachment of the wealthy living in the cities from those in the surrounding small towns and countryside have all contributed towards a total breakdown of the grid of power. My painting has reflected this and become increasingly concerned with reflecting what happens when a society finally collapses into decay and corruption.

For the last few years, I have been making paintings of the decay taking as inspiration sea defences around the coast near where I live in Sussex. Metal sheets were used to cover concrete defences often placed over the top of drainage systems. These were put in in the 1950s and have not been maintained and so have decayed. This period of decay parallels the period during which I developed and then abandoned the use of the grid in favour of working from photographs of the decay of these defences. In my mind I see their decay as symbolic of the decay of my country. Battered by waves loaded with shingle and corroding because of age, the steel sheets crumble under the assaults of the sea and the detritus of civilisations. Beneath them the concrete also is being whittled away by the impact of shingle driven by 30 foot waves at 30 miles an hour into the coast much in the way in which the shingle crumbles our chalk cliffs.

Under the weight of millions of incomers, the bonds that held our society together are starting to break. Those in power seem only to worry about monetary value not about our sense of community or identity. They dither. All of them dither. There are no strong leaders amongst our current politicians. The results are much the same as the continuing impact of the sea on the sea defences. Corrosion and decay. The one glory from it all is that the decay generates colour and a final flowering of culture.

It is said that every empire at its collapse experiences a period where there is an enormous flowering of the arts: in literature, in music, in the Fine Arts, in architecture, in design generally. I have been privileged to live through this glorious time, now coming to a close as the final disintegration of our social systems, tax structures and our cities comes about. Who knows what might survive of this culture. Our language certainly, the richness of Shakespeare, Milton, Byron, and others will be treasured by those outside our culture as much as they have been by those within. The impact of our culture on the 20th and early 21st centuries has been remarkable. In my own small way I have contributed to this flowering and I am proud of what I have achieved.

Now with sadness I stand on the sidelines and watch as Greeks and Romans before must have watched as their cultures were subsumed by Barbarians. England will be, like the Greek Parthenon, like Imperial Rome, a memory and a collection of broken stones.

Follow me on twitter Patrick A. Goff (@patricktheart) / Twitter

Or on Facebook

See my work in the Gallery on this site

Note: In 1951 the census records England as being 41,573,585 (now 56,490,048); Scotland 5,095,969 (now 5,480,000); Wales 2,596,850 (now 3,107,940); N.Ireland 1,370,933 (now 1,905,000, a rise altogether of 18 million souls, and still for our politicians this is not enough despite there being no plan in place for anything – not health, nor education, nor transport, nor owt else.

Profound, Patrick. I’m a visitor walking your land, England, which formed me growing up in the 60s and 70s. I find little or nothing I disagree with.