“It’s your Christmas present” she said, “a week in Lanzarote. The sun will help your healing”. Yes, a year after operations we still think of my healing. I have added over a half inch of muscle on my thighs, starting to rebuild the 4 inches I lost in hospital. My love looks after me so well, but inside I thought ‘Lanzagrotty? OMG’. I was wrong. The island was a spectacular revelation, an austere volcanic rock in the Atlantic with the most spectacular arid landscapes.

Arid farming- semi circles of volcanic rock channel moisture from the prevailing (and constant) winds for each plant.

The architecture of the island is typical of many Mediterranean islands vernacular, but the climate is moderated by the Atlantic. Arid farming techniques on volcanic rock were fascinating. With just 8 inches of rain a year (26 inches in Brighton, 56 in Blackburn, 100+ at Ribblehead) farming techniques have developed to enable the production of local wines and some foodstuffs. It is the tourist industry that supports the economy, with over 4 million visitors a year, increasing since fears of violence in the Muslim world turned British eye away from the Eastern Med towards the Canaries. The British, I was told, make up 60% of the visitor numbers.

The architecture of the island is protected by strict building codes, developed by returning ex-pat artist César Manrique when he recognised the potential of Lanzarote as a tourist destination in the 1970’s. His Foundation now acts as an environmental watch dog to preserve the attractiveness of the vernacular – would that we had a similar body defending us from the future slums currently being developed in the UK.

Manrique was born in Lanzarote in 1919, son of a food merchant from Fuerteventura. Like many tourists he enjoyed the beaches, his parents having a house next to the ocean (well Lanzarote is a small volcanic island in the Canaries just 38 miles long, so most houses are close to the ocean). Major eruptions ending with the largest in 1824 left an almost barren and spectacular landscape. Manrique said:

“My greatest happiness is to recall a happy childhood, five month summer vacations in the Caleta and the Famara beach, with its eight kilometres of clean and fine sand framed by cliffs of more than four hundred meters high that reflected on the beach like in a mirror. That image has been engraved in my soul as something of extraordinary beauty that I will never forget in all of my life.”

Echoes here of Monet and his garden, and it resonates with my own relationship with the Sussex landscape I walk in around Seaford.

Manrique fought in the Spanish Civil War as a volunteer in the artillery unit on Franco’s side, the experience scarring him and he never talked about it. Returning home after the war, he took off his uniform, doused it with petrol and burned it. He attended the University of La Laguna to study architecture, but after two years he quit his studies. He received a scholarship for the Art School of San Fernando, where he graduated as a teacher of art and painting.

Manrique had his first exhibition in 1942 in Arrecife. In the 1960’s he had multiple exhibitions in Spain, Germany, England, Sweden, Italy (Venice Biennale), Austria, Brazil, Japan, USA and Finland. He had a major exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in 1964, living in New York until 1966. A grant from Nelson Rockefeller foundation allowed him to rent his own studio. He painted many works there, absorbing the work of and socialising with many of the artists of the day such as Pollock, Warhol and Rothko. However, his views on creating in the city were made clear (and are echoed by my comments in ‘the Hive’) when he observed:

“Man in N.Y. is like a rat. Man was not created for this artificiality. There is an imperative need to go back to the soil. Feel it, smell it. That’s what I feel.”

Returning to Lanzarote he was shocked by a new 17 storey hotel erected in the capital, Arrecife. Reacting to that and aware of the tourist potential of Lanzarote, he successfully lobbied to encourage sympathetic development for tourism by creating a series of planning rules to maintain the integrity and beauty of the built environment on the island. Most buildings are white, and there are restrictions on the height of buildings and colour of windows etc, to just three colours a blue, a green and a brown.

His two years of architectural training became useful and he masterminded many significant buildings both on Lanzarote and beyond, the drawings carefully proclaiming him as the project manager, not the architect. He was an early environmentalist and said of his home island:

” When I returned from New York, I came with the intention of turning my native island into one of the more beautiful places in the planet, due to the endless possibilities that Lanzarote had to offer. For me, it was the most beautiful place on earth and I realize that if they [his students] were capable of seeing the island through my eyes, then they would think like me. Since then I made it a point to show Lanzarote to the world”

Lanzarote is considered by many César Manrique’s most important work of art. His work and influence have marked the external aspect of the island. The natives say that he has “made” Lanzarote. His desire to live with the volcanic lava led him to build his own house in the Taro de Tahiche, now open as La Fundación César Manrique .

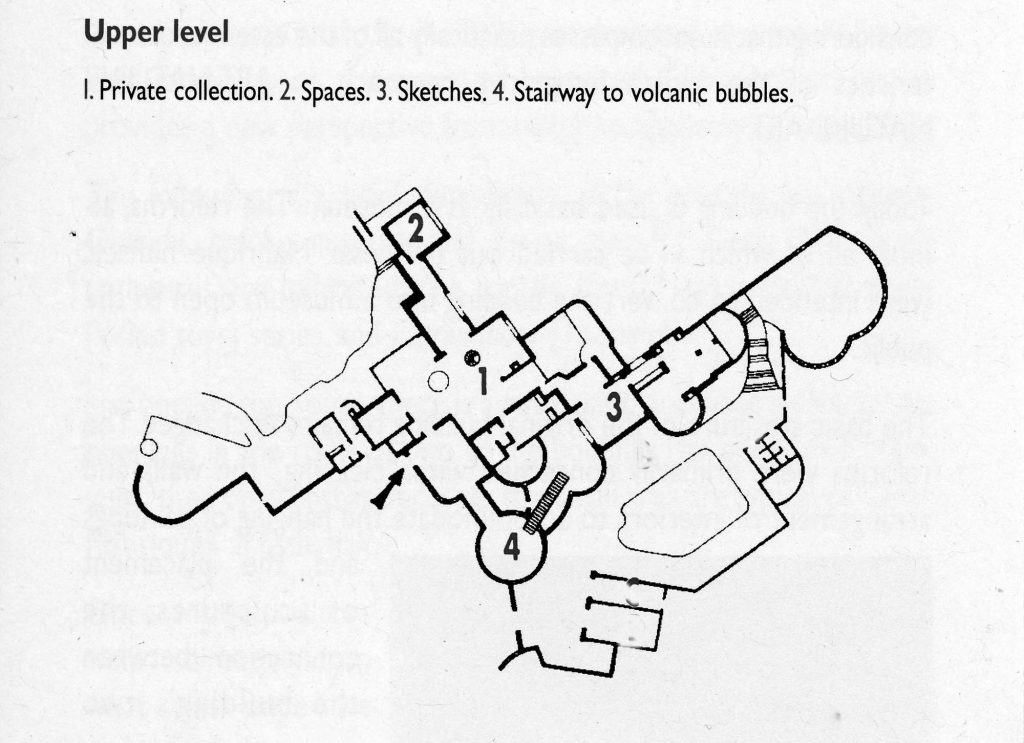

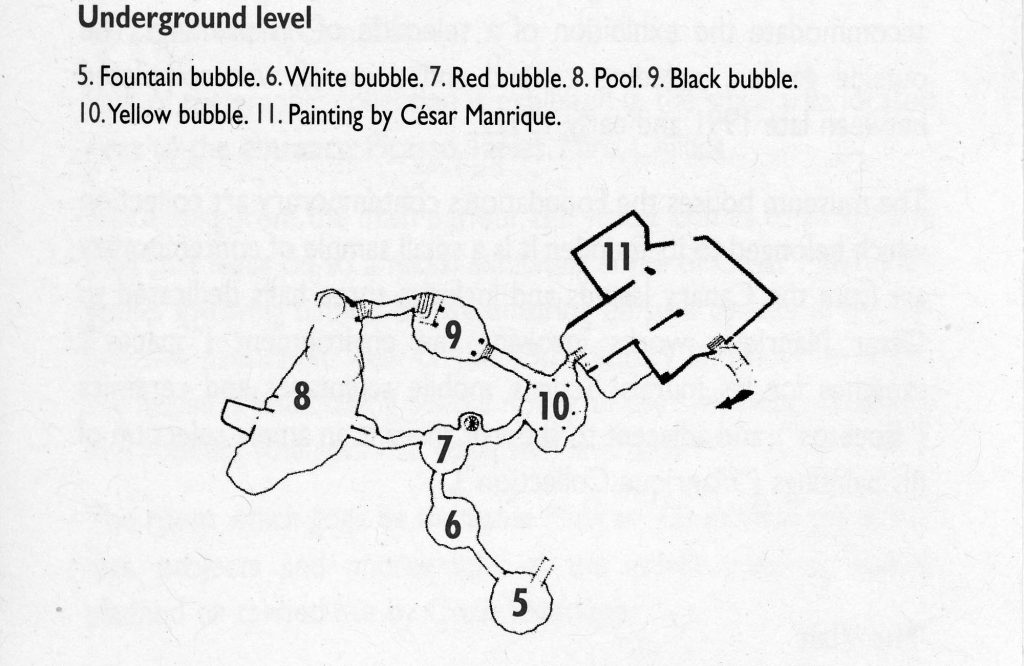

This spectacular house is melded into the landscape using five ‘bubbles’ in the lava flow to literally make living spaces within the characteristic Lanzarote lava, the single story white building above demonstrating how contemporary space can be created within traditional architecture Lanzarotian forms. It is beautifully expressive of the island terrain, using it to create cool living spaces. The bubbles work in relation to the climate with spaces that are both internal and external simultaneously, as the photographic images show.

Cleverly and somewhat ironically as he was killed close by in a car crash, the small café and souvenir shop have been created from his garages, but the original living and work rooms have been created within traditional vernacular building forms that demonstrate how well the contemporary interpretation of the vernacular can create modern minimalist interior spaces. Reflecting the movement of the lava it lies within, the house flows organically from one space to another, with interlinking staircases to the rooms built into volcanic ‘bubbles’ in the lava flow below ground level. The bubbles in turn are linked with tunnels that look crudely cut through the volcanic rock, but which are sophisticated links carefully constructed and painted white as the exterior of the vernacular buildings are, this emphasising the intrinsic colour in the lava rocks.

Whilst on the ground floor large windows are positioned to frame views, in the bubbles advantage is taken of the climate to leave central openings to the sky, several with trees (themselves a rarity on Lanzarote) growing up through them. This allows light to spill in whilst providing plenty of shade from the summer heat, when temperatures can go past 30°C. The bonus of the bubbles is that they also protect from the endless winds that buffet the island.

Currently the building shows some of the artworks the artist collected and created whilst receiving over 300,000 visitors a year. The approach and entrance does not prepare the tourist for the shock of the beauty of the building itself, and it is worthy of inclusion on any architect/designer’s bucket list. Hobbit like, the structure is far bigger than the restrained external appearance indicates, and the exuberance of Manrique’s artworks is only hinted at in the mural on the small garden terrace wall.

Manrique died in a car accident very near the Fundación, his Lanzarote home, in 1992. He was aged 73. His legacy is the beauty of Lanzarote, protected by the building codes he was instrumental in creating.

Gourd tree in a ‘bubble

Gourd tree in a ‘bubble

Sign up in the column on the right to receive these writings ‘hot off the blog’

Strangely familiar. Iceland with the heat turned up.

I visited this place just over a year ago. Quite stunning!