We are going through a period of change again. Periodically society gets shaken up. Right now we are seeing idle hands taking advantage of the reduction in police numbers brought on by a policy of balancing the national budget, itself blown apart by the CV-19 infection. I wish we could just stop news of the USA since so many idiots conflate our problems, our policing, with theirs. I have visited and worked the States and there is no comparison to be made between us. We don’t even share a common language.

The previous bout of change was caused by greedy bankers in 2008, a drama made into a crisis by a failure of political will that let the crooks off scot-free. Many were damaged and more lost financially whilst the culprits not only kept their incomes and pensions but their businesses too. Like many running a small business at the time I only just managed to stay afloat. This was the second time my business had been slashed by financial stupidity from banks – the previous crisis caused by John Major chasing the ERM basically cost me everything I owned in the 1990’s. Of course, again, the perpetrators, the politicians and financial wizards all escaped with their lifestyle and income intact.

I seem to have some resilience though, maybe because I was born in 1947, the worst winter in the last 100 years. It was the lean years just after WW2 and there was still food rationing – indeed in some ways worse then than the war years as we sacrificed foodstuffs to feed the Germans, under pressure from the USA, who also wanted repayment of the loans they gave us to buy weapons from them, loans we only paid off about 2011. They have never really have forgiven us for the beating we gave them in 1812, have they?

My crib was the bottom drawer of the chest of drawers in the room my mum and dad rented. Dad was an RAF corporal nurse and the RAF was to be part of my life for the next 18 years. We never had a house, just a succession of married quarters (see my ‘Service Brat’ blog). I left home to go to art college and trained as a fine artist at what was considered the ‘Cambridge of the Art World’ Bath Academy. Art College teaches you many valuable things but making a living as a fine artist is not the easiest path to take.

I took a job as a bar cellarman in a pub in Patcham just outside Brighton. I enjoyed it, liked the landlord (who taught me how to make good omelettes) but could not stand the landlady’s yappy little dog. I used to have a steak pie for my lunch, standard pub fare. Out of the freezer into the microwave, which had a clockwork timer and a separately activated oven. One morning whilst stocking up the bar I was so fed up with the dogs yapping at me that I popped it into the microwave. Hearing the landlady coming downstairs I turned on the timer. Of course, tempted though I was, I did not activate the microwave cooker, so no risk to the hound. The timer pinged and the landlady opened the door to take out (she thought) my pie, to be greeted by her yappy dog.

She fired me on the spot of course. As I left to get the bus the landlord came after me. ‘Now I’m in for it’ I thought, but no, he couldn’t contain his laughter, gave me a couple of weeks money and told me he wished he’d thought of doing that himself…

I found freelance work as a screen printer for a while but then was offered the opportunity to run a bar. It suited me as I could paint in the early mornings and afternoons, having taken studio space in a squat just off Grand Parade in Brighton. This led to my first shows in a gallery in Brighton, the first of which almost sold out. Bouncing back to my rented flat in Brunswick Place I had time to consider what to do with my bounty. Prices in Brighton were way beyond my budget, but I thought maybe they would put a house within reach somewhere else. So, I researched house prices nationally using the local papers then available in the public library, this being 1974. I had a budget of £450 (this was 1974, equating in 2020 to around £5,000!).

Even then it was a stretch to find a house and my search identified just two areas where I could live mortgage free. I settled on Darwen, a mill town in Lancashire. I had £200 in cash and another £250 readily available so approached my bank if central Brighton to borrow until my additional funding came through. The bank manager of course wanted to know what I wanted the money for. I explained and he said what was the mortgage repayment. I said “no, £450 is the total cost”. Being in Brighton where prices had at least one if not two noughts on the end, he smiled at me, “No” he said, “it doesn’t work like that. You put £450 down as a deposit and then pay so much a month, it’s called a mortgage”. I replied in turn “No that is the full price.” He looked at me then said well, “as it was less than a year’s rent in Brighton if whatever I bought fell down after 12 months I was in profit”. So I bought a stone built 1860 terrace, originally a clog makers house.

I had no job to go too, so it was a little bit of a gamble. The house had no bathroom being a two up two down with an outside loo, but my girlfriends parents lived up the road, so every weekend we visited to bathe. In between we did what they call in Lancashire ‘possibles’. You wash up as far as possible, down as far as possible and once in a while you wash possibles…

I found work as a dustman which brought with it a daily ticket to the town bath house where in a white tiled private bathroom a huge tub allowed me to exchange my ticket for all the hot water I wanted to wallow in. Being a dustman fitted what I wanted. Starting early each day I was usually finished by early afternoon and could spend 6 hours a day in the studio, and I began exhibiting at the rate of 3 shows a year – but that is another story. This is about life then in a dustcart over ‘t’moors’.

There were four of us in the crew. Our driver would get us back to the yard finely timed to ensure it was too late to be sent out on another job, but in time for us to do other thing – for me to paint but for him to look after his sheep as he supplemented his income from subsistence hill faming on t’moors… my other two companions were true Lancastrians and I quickly acquired the accent and began to learn the vernacular, complicated by one of them removing his teeth when we started the round making his accent even more incomprehensible to my southern tuned ears.

We were adept at moving deliberately when being timed by motion study guys but had all sorts of tricks to speed up when we wanted to make sure we just used the half day. Part of the round was to visit remote homes on said moors. One of us would leap out of the slow-moving truck as it approached the farm gate and open it then run after it to regain the seat, often without the truck doing more than slow down. On one occasion the crewman didn’t reappear. He had leapt out of the cab into a large grass covered hole. Not so deep he hurt himself, but his embarrassment was compounded when we saw his arm and hand appear and start patting around the lip of the pit. It seems his teeth, stowed in the top pocket of his overalls, had been dislodged in his fall…

Many of the properties we serviced were those of the wealthy who always seek to stand alone, but many were small farms, still, in 1974, using shit pails in outside loos. Some of these were even two seaters, something I had only seen before in museums. Our job was to pull the bucket out, each of the ‘brick outhouses’ having a small door in the side for this purpose. We then had to find a spot, usually marked by nettles etc. from earlier visits, where we could strain off the liquids. Solids went into a black bin bag which joined the rest of the rubbish in the back of the dustcart. Putting the bag into the dustcart was in itself an art form. Time it wrongly and the bag would explode throwing ordure over the operative – in which case we would insist on them riding the rest of that day on the tailboard.

I was shocked, as no doubt you are on reading this. It was positively something from a past era. Seems the farms could have mains drainage if they put it in at their own expense. Connecting to sewerage systems could mean digging drain runs hundreds of yards long, beyond the pockets of what were in the 70’s marginally viable farmsteads. I questioned why there wasn’t a pump system of some kind to tow behind the dustcart. It seems there had been one, but local politicians considered it an unnecessary expense and had sold it off. All the rest of that first experience I thought about what was going on and finally had a chat with our driver. He eagerly assented to my suggestion that we change the order of the round. It meant that we did councillors houses last and after a couple of weeks of dripping detritus on gravelled driveways a towed pump miraculously reappeared…

Interestingly even then newspaper was being collected for recycling, but the mill processing it closed because the price it received for the reprocessed paper didn’t cover its costs. Recycling was something dustcart crews were good at. My partner would be working at home when a knock would come on the door. Two dustmen would come in carrying a better table to swap for one acquired this way earlier. One man more than doubled his wage by collecting electrical cabling from every dustcart load, burning off the coatings and selling the copper to a local scrapyard.

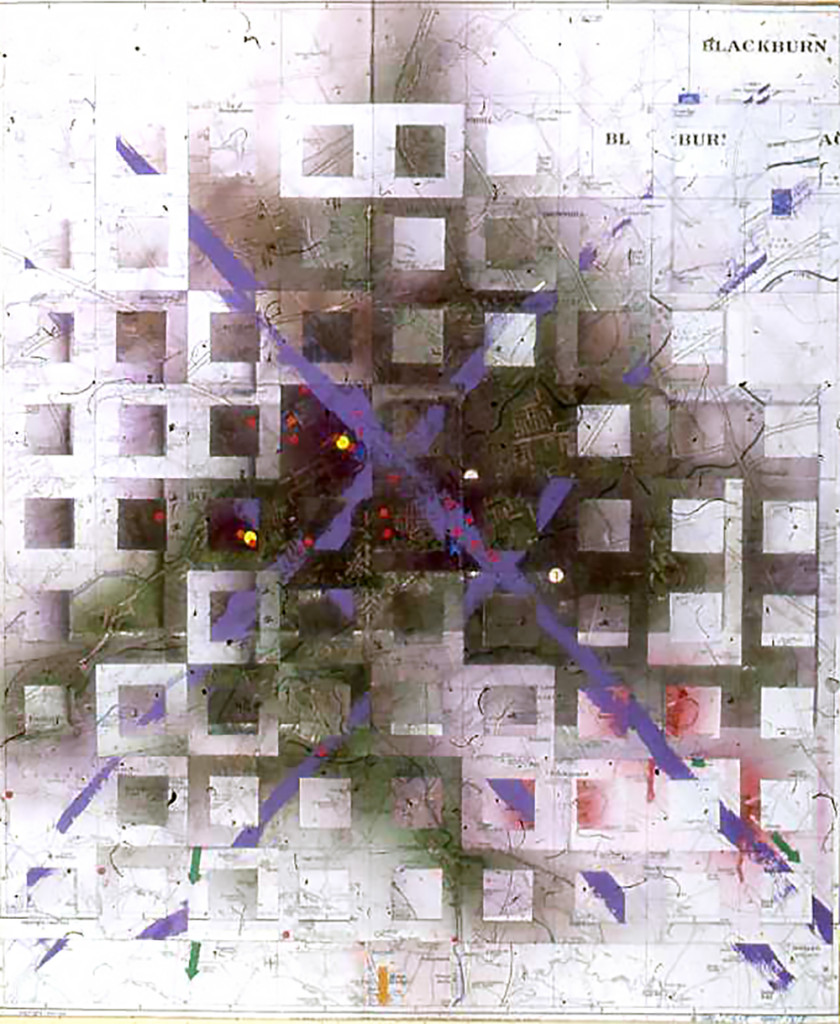

I had a Review of my work in the Guardian that referred to it being “sexuality hemmed in by spiky crystalline walls”. This was the spiky crystalline wall to my back yard…

Now much of what we sorted out – pots and pans, bits of furniture etc., goes into the maw of the charity industry for resale, but in the early 1970’s dustmen were early pioneers of recycling. Hopefully we have progressed so that they no longer sort the sewerage from farms, maybe cess pits and the like have saved them this job, although the regular emptying of squatted properties no doubt continues that we demand of these heroes that they handle the shit we leave behind. I found it difficult to believe that in the latter half of the twentieth century we still used such 19th century techniques – ‘nightsoil men’ we used to call them, when contents of outside toilets were harvested to spread on the fields .

My time as part of this team was limited. It was very productive in both remaking the house and in allowing the development of my painting. I was eventually offered better paid work as a screenprinter, an occupation that I believe led to my developing cancer many years later. The solvents used in the late 70’s were carcinogenic, killing world famous printers such as Chris and Rose Prater. But that progress is another story…

Recent Comments