The Prado Museum, one of the world’s biggest art galleries, cannot find 885 of its own works, according to Spain’s Audit Court.

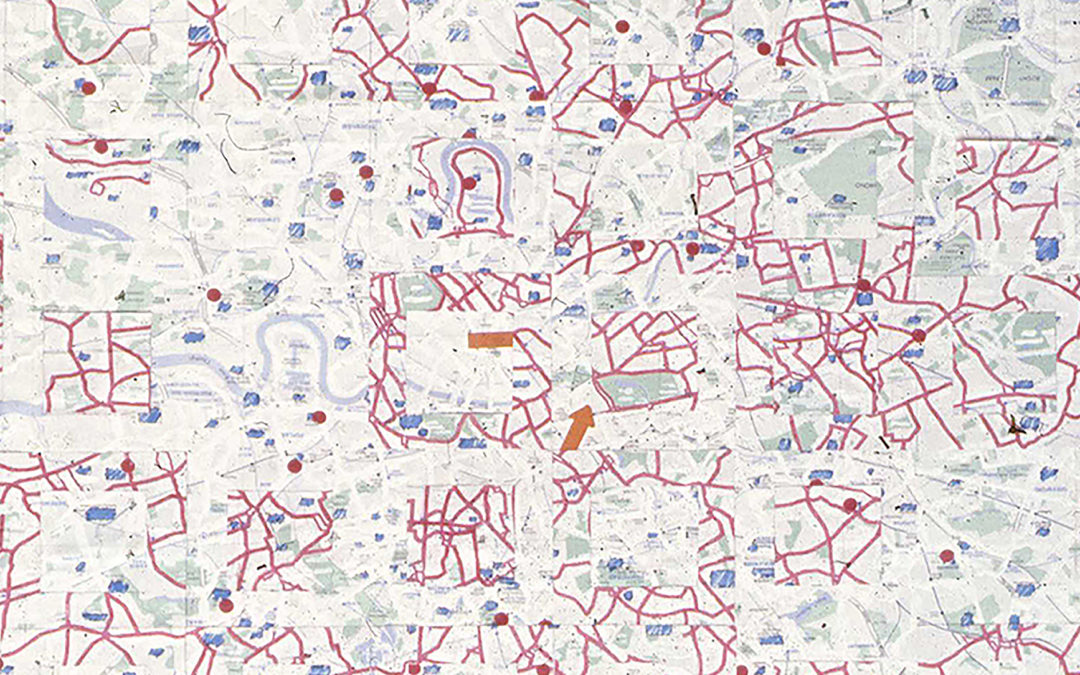

Some years ago, I was a part of a group of artists organising group shows in galleries throughout the English North West, as well as my solo exhibiting. I had a very large painting which was brilliantly hung appearing to me (I admit bias) the star of the show in one large gallery. My map series was also there but when I was approached by the gallery director/curator to speak to the press I was delighted. “it’s the Observer” he said. Doubly delighted, as at the time the Observer ran a colour magazine carrying an image every Sunday as painting of the week. National exposure could only be good.

My friend Alison Williams with her ceramic caricature of the nationally known local MP and I both went to meet the photographer. We were of course, quite excited and I said to the man with the camera “What brings a national London based paper up to this neck of the woods?” He grinned, “Nay lad” he said “I’m with t’Rochdale Observer”. As the Victorians would say, ‘collapse of stout party..’ Fame is elusive.

Many of the northern galleries were in lovely Victorian building endowed with extensive collections of Victorian paintings by past industrialist when the North West rivalled 1990’s California as the richest spot on earth. For example, Manchester is famous for its collection pre-Raphaelites, Blackburn for its enormous collection of Japanese prints . In conversation with one gallery director newly appointed to post I asked him about the local collection. He said he had only been in post for a few months, and one of the first things he did was to audit the collection. His first reporting session to the full council became something of an embarrassment as he had to report that some 47 paintings were missing. He had reported the matter to the local police but was still surprised by the shocked concern shown by the councillors. It turned out that it had been a tradition for councillors to borrow from the collection, and some works had not been returned. Nearly all the missing artworks came back in the next couple of days…

Recently a government minister who lost office was stopped emptying his government office as he was taking home the painting from the large government collection that had been hanging on his office wall. When state organisations like the Tate have warehouses full of pieces it is not surprising when audits show the occasional piece missing. I know of one college where a major work was destroyed because it was in the way. In another a valued miniature piece of a wall painting disappeared when a principal retired. So can state purchase or patronage be a good thing for an artist? Or does state patronage determine the nature of the product?

There are extremes of state patronage of course. In Britain we have an Arts Council that quite cavalierly dispenses money to artists and arts organisations. Currently the figure is over £100million annually. I was fortunate in my early years to be given two grants. Small the first year, to help finance my first exhibition in Brighton, I offered an account of how the money had been spent. ACGB was shocked at the idea they should check how the money had been used and said an account was not necessary. So the following year I applied and received double…

I never became directly reliant on ‘state aid’ but did eventually subsidise my studio and artwork by teaching, an honourable and traditional route many painters follow until they find that teaching can drain creativity quite quickly. I was fortunate. A good college, a supportive head of department and a great bunch of students who were happy to have me work on in the evening with them and didn’t object to my having a large canvas in the studio too. This happy period was capped when Helen Kapp (see Hockney etc.) purchase on behalf of North West Arts Association one of my large canvases for their ‘Pictures in Public Space’ scheme.

When the Arts Council announced they had digitised their collection I expected to see the painting listed. North West Arts received their funding from the Arts Council, something over a quarter of a million, a great deal of money in the 1970’s. Imagine my surprise when not only was the painting not listed but the Arts Council denied that North West Arts ever existed…

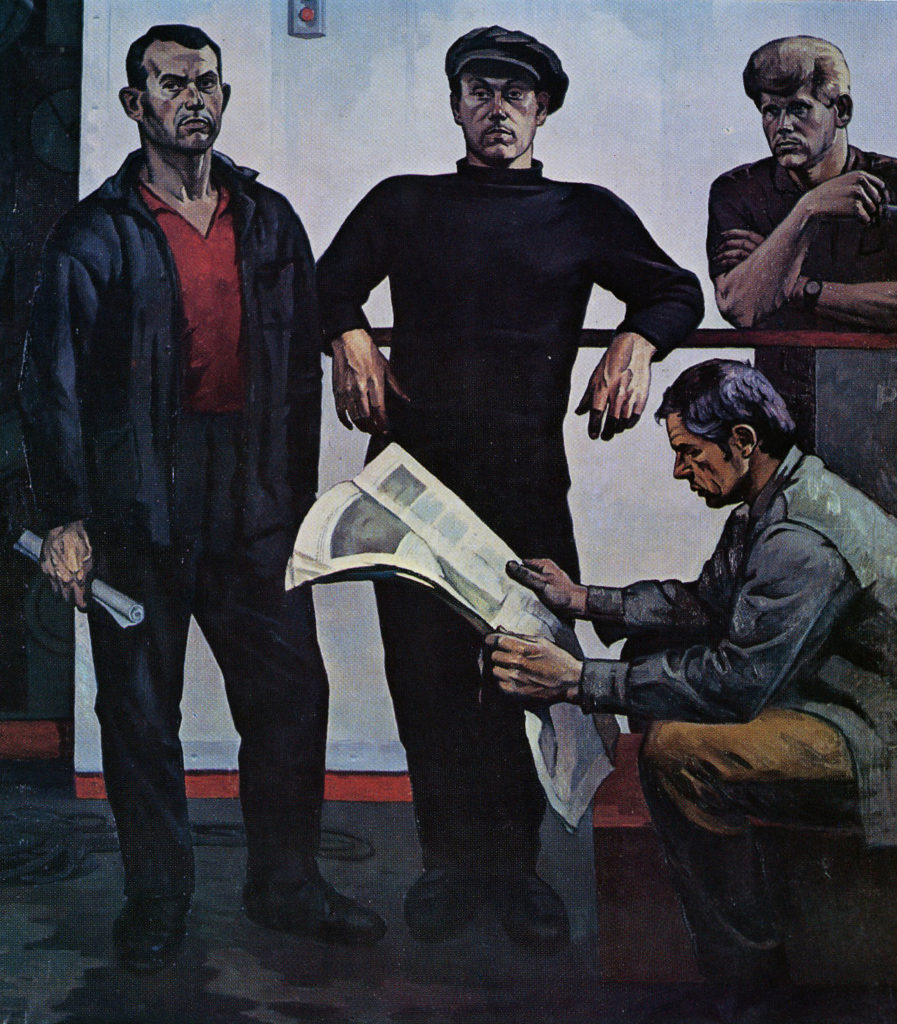

During the Soviet revolution artists formed and important part of the state apparatus. ‘Agitprop’ trains carried the Bolshevik message from the cities into the countryside and the state very quickly realised the propaganda value of art. Fine in the early years, but the state also quickly came to realise the difficulty of controlling artists. We are individual thinkers, non-conformist often, lateral rather than linear thinkers. Controlling art is rather like trying to herd cats or push a line of string.

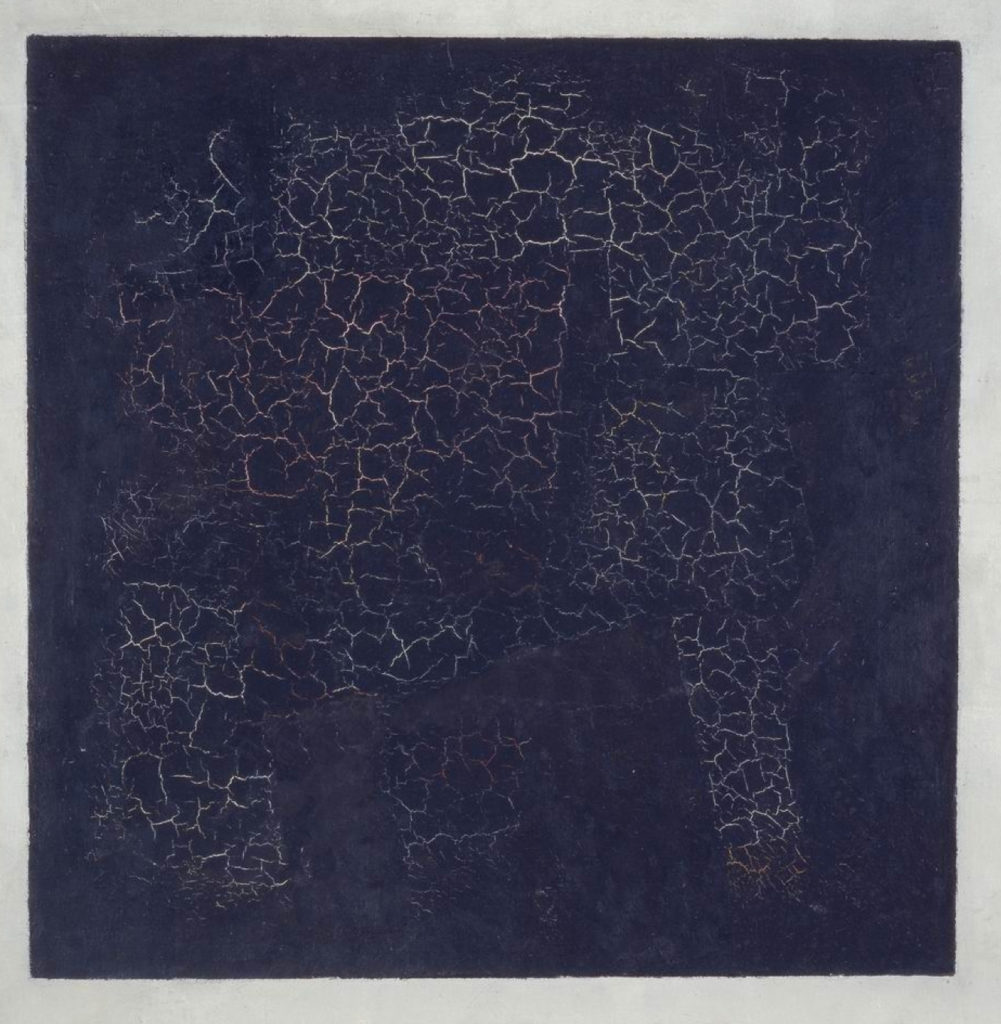

Initially artists like Tatlin, Mayakovsky and Malevich, famous for his ‘Black Square’ from 1919 were heroes to the revolution. Malevich’s career reflects the decades surrounding the communists. In its immediate aftermath, vanguard movements such as Constructivism were encouraged. Malevich held several prominent teaching positions and received a solo show at the Sixteenth State Exhibition in Moscow in 1919. His recognition spread to the West with solo exhibitions in Warsaw and Berlin in 1927. From 1928 to 1930 he taught at the Kiev Art Institute, along with Tatlin etc., but the start of repression of the intelligentsia forced Malevich to Leningrad (now again St. Petersburg). From the beginning of the 1930s, modern art fell out of favour with Stalinists. Malevich soon lost his teaching position, artworks and manuscripts were confiscated, and he was banned from making art. In 1930, he was imprisoned for two months.

Kazimir Malevich, 1915 Black Suprematist Square, oil on canvas,79.5cm x79.5cm, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Under the Soviet system artists could be paid to paint. They presented their ideas to the local ‘block representative’ of the party. If the idea was liked approval would be given for the purchase of materials – no approval, no paint. All very well being paid a salary to create but those who are paying expect to control the nature of the output. It was fortunate for the history of western art that repression was such a part of the East European art scene under dictatorships as a steady flow of creative geniuses fled westward giving rise to movements such as the Bauhaus. The current repression of dissenting voices in our Universities and educational institutions mirrors Stalinist techniques of repression

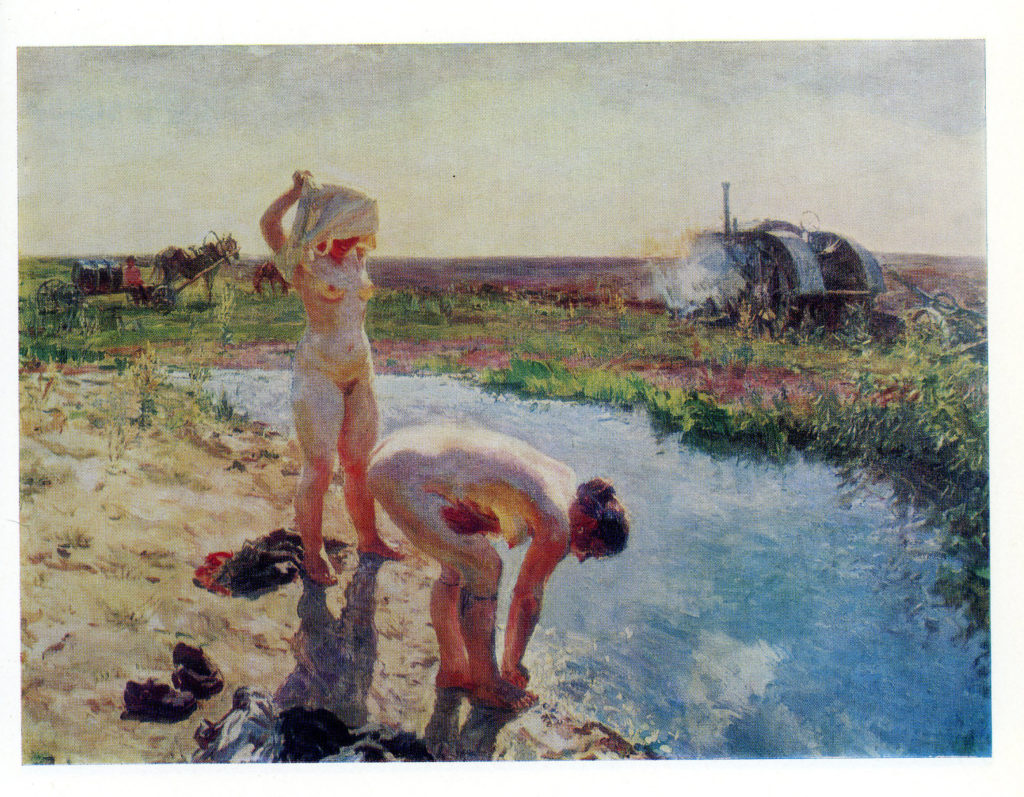

In Britain in the 60’s when I joined art college, we had the last days of the National Diploma in Design. The painting paper that year was the last I think, and the task set was to produce a harvest scene which had to include everything on a list of items on the exam paper. Art college in the sixties existed outside the University system. In fact for those of use choosing art college for our further education the degree awarding Fine Art courses, and there were I think only 4 at the time, were regarded as an academic joke, theoretical rather than practical. From the art colleges came a stream of creative people – painters, sculptors, musicians, photographers, animators, and designers of all types. Alas now the University system prevails.

The independence of the art college was created by the Victorians who, seeing the rise of industrial rivals like the USA and Germany, wanted to maintain Britain’s dominance through a stimulation of the invention and creativity that had been behind the industrial Revolution. To those who rule this system was a threat both in the way designers and artists thought but also because the colleges were expensive and did not fit into the education matrix as envisage by government departments. As art college became part of universities at the end of the twentieth century so many of the esoteric and expensive bits were jettisoned removing much of the creative potential from the system, and emphasising the uniformity of examinations across courses – for example the requirement to have English and maths before entry (took me 5 tries to get maths yet I ran successful businesses with large turnovers and staff) or the instruction to test drawing with written test

The students are as bright as ever, the teaching, where it happens, is as good as it ever was but delivered in much smaller doses to much larger groups. Like the Arts Council, government organisations are focussed on delivering to the point where they cannot see what they have lost if forcing conformity into processes. As Britain comes out of the EU and needs to look to regenerating its industries it needs to release the creativity of people again. In the 1980’s I was invited to give a talk to a group of Japanese design managers from some of their most respected large companies. They were concerned that their system emphasises the group in a way that encouraged conformist thinking whilst in Britain they saw and wanted to understand how our system produced rebellious creative individuals. Many leading eastern manufacturers had their design studios in Britain or chose Brits as their heads of design.

As a nation we have begun to look for subsidy, for support, in a way that the creative country of the 1960’s, 70’s and 80’s never did. We need again that sense of free wheeling brigandry that allows individuals to pursue their ideas in an environment that doesn’t tie them up with rules and regulations, that encourages self-reliance, invention, and invests in developing individuals to their maximum. We need to produce in numbers again those rebellious creative individuals. We need to be quick to support inventions where in the past our inventions have been profitable for other nations – televisions, computers, jet engines, tilting trains etc. etc.. It is said that we invent for others to profit. We allow British companies like LandRover to be bought and their intellectual property then exported to the profit of manufacturers abroad. It is time we stopped the rape of our industries. Our ideas need to be developed and made in Britain. It starts in our education system where conformism and a focus on exams is antithetical to creativity. There are leaders in places who have much to teach others, but the dead hand of the governmental administration and our poor managerial class needs changing to free them up.

We need more lateral thinkers. Yes, more like Dominic Cummings, willing to challenge, looking for change. We need to become makers, movers and shakers, again. We need to kick the machine.

Recent Comments