Nancy and Jim visited today. Nancy was one of the senior assistants in Olga Polizzi’s office at Forte and was the person who approved my design practice as one of the group of practices working on Forte hotels in the 1980’s. She and Jim wanted to know how Goff Associates rose and fell as a practice, so this is my story of a mad whirlwind 20year period in my life.

In 1979 I was happily teaching on the Foundation and SIAD Graphics courses at Blackburn tech, turning young people on to art and design, whilst exhibiting and selling my paintings two or three time a year. I was also working on a Ph.D at Lancaster University. I was instrumental in forming a large group of artists’ and crafts people and we had many exhibitions (See my profile on my website for more). I became an invited artist on, for example, the opening of Liverpool Academy, and as the featured artist at Lancaster Literary Festival with my ‘memory maps’ of Brighton and Blackburn. My partner had completed an MA at Manchester University and was working for a design practice in Preston. Then it all started to come unglued.

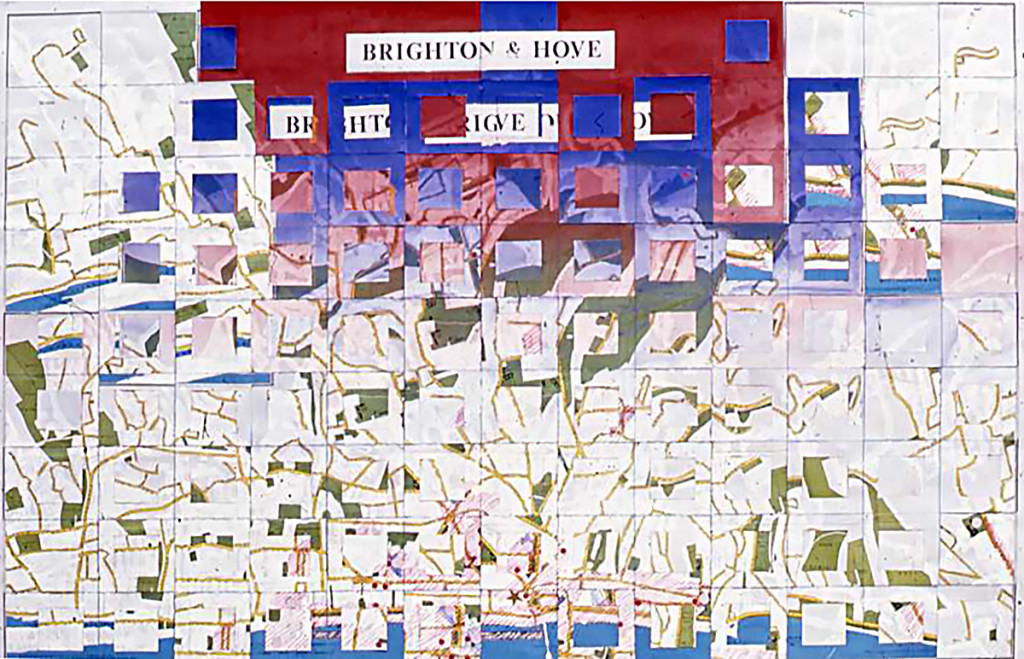

Memory map of Brighton. Events are coded and then collaged, Playing with how we read images, art as language. Want your own memory map? I accept commissions….

My partner’s ambition was to work in design in London, and whilst I agreed that for me as an artist London was a long-term focus, I was unprepared for the speed with which I was pushed into applying, and gaining, a senior post in a London college. We had enough from our Preston house to buy a decaying Georgian terrace in Camberwell, South London and I set about building a vocational art centre south of the river in Southwark. At the same time, I set about replumbing and rewiring the house whilst my partner was head hunted by a leading hotel design practice.

I grew the college arts programme from some 40 students to about 200 in less than 5 years, winning plaudits from inspectors and politicians. I had to abandon the Ph.D. and my own work also suffered (although I continued to paint) as I supported my partner in her career. When she became pregnant, I persuaded her if she was to work from home then it was sensible to set up as a business, and so Goff Associates was born in 1982, aided by her employer subcontracting two interior hotel projects to her.

We had entered a competition for a couple of new hotels, and won one new build 100 bed project, so in 1984 I resigned my teaching post and we bought a shop further down Camberwell New Road, converted it into studios and sample rooms, and began to expand the practice which had grown to fill my studio rooms. After an exhausting 18months providing the ‘back office’ tasks as well as holding down my teaching post I could not continue, I was on the verge of a breakdown. I would be in college all day then evenings spent sorting sample boards, typing tender documents, researching products etc.. Our newborn lay in his carry cot beneath a drawing board, on one occasion being found covered in colourful carpet threads having dismantled a weaver’s tuft box.

1999 My carpet design for the award winning Celtic Manor hotel, designed with Brinton’s design studio to reflect the plasterwork ceilings

Camberwell was an easy walk to central London, although I cycled often. It was close enough to the centre we could hear the IRA bombs exploding. Our area was used to film a TV crime series as much of the Georgian building had been cleared by Labour council and German bombers and replaced by poor quality housing. Even so I was shocked when the Met Police allowed a film company to blow the front off the shop next door to ours during filming. The largely run down area proved to be difficult to attract designers to work in so I guess it was inevitable that we would have to move again as we continued to grow the practice.

I had also made a presentation for Nancy Lee at Forte’s office which had it seems impressed, and one day 14 refurbishment projects dropped through the door all at once. We also started a long ten-year relationship with a south coast hotel, lifting it up to become a premier conference hotel, designing a suite for Margaret Thatcher and rooms for the teenage royal princes, receiving scrutiny and clearance from the security services. The practice rapidly outgrew of Camberwell office, and we found a lovely new office in 2,200square feet in Chelsea’s Lots Road, which I used to cycle to from Camberwell. It was an exciting and rewarding time in many ways, during which I continued to be an external assessor on vocational and degree programmes. Our design work featured in magazines and newspapers after I started writing about our work (including in an architectural magazine in Hong Kong), and we worked on hotels from Carlisle in the north to St. Helier in the south, from Aldeburgh in the east to Bristol in the west.

Ultimately, Goff Associates grew to 22 designers and started to win design awards including 2 international design awards for the Celtic Manor Resort in south Wales, which conscious of my Welsh ancestry I insisted should be very Welsh, complete with dragons (one of the dragons in reception has its foot on an English shield), Celtic carpet designs and Welsh artists art works. Alongside the development of the Celtic Manor over many years we also created and refurbished over 300 other hotel projects. The interiors industry had grown in skill and importance through the 1980’s and into the 1990’s as Thatcher cut bureaucracy, we started to dream big dreams. Another designer, Richard Daniels, and I started discussion about starting a factory to manufacture casegoods for the industry, my own practice having already designed new ranges for 3 different UK manufacturers. (We met and lunched at Chelsea Arts Club, where Richard proposed me for membership. I was black balled as I was apparently not a painter enough for them.) It looked like we could continue the industry growth and cooperatively replace imports by expanding into manufacturing. We started to contribute to the construction of an hotel in Canada, were the only Interiors practice recognised to work in Jersey and a client was looking at building his first hotel in France… We had been growing steadily, profitably, and saw no reason to think things would change.

In one of our regular meetings with our accountant I looked at our expansion and suggested that our partnership was overdue to become a limited company to match the increase in turnover and responsibilities. The accountant was already calling us ‘his’ millionaire designers. To my horror he advised against it as we would have a very large tax bill for making the change. He and my partner overruled my objections and so the base was laid to the disaster that was to follow.

Shortly after, the politicians went mad and the establishment, perhaps jealous or threatened by the success of the nouveau companies inspired by Thatcher’s market driven approach, set about destroying her and the success she had engendered and the many nascent ambitious companies that her policies had allowed to grow energetically. The bone-headed Tories under John Major engaged in some sort of suicidal economic policy that saw base rates reach 16% whilst at the same time enraging Arab politicians so that threats of war were thrown around. With our Chelsea office on a standard commercial mortgage at 5% above base we found costs accelerating out of our control as simultaneously under the threat of terrorism the hospitality market crashed. London hotels with traditional occupancy rates in the high 80% saw occupancy shrink below 20%. Refurbishment projects were cancelled. One hotel chain refused to pay us fees it owed of over £100,000 because it had cancelled the project after it had been tendered, bankrupting a number of construction suppliers. Income went below break-even for the first time as costs continued the interest driven rise and inflationary pressures. It happened unbelievably fast. It became unsustainable as we waited for the fools in the Treasury and the Bank of England to see the damage and destruction they were doing. It was unsustainable.

One story to illustrate how unbelievable this economic suicide was to those of us on the ground. The success of the Forte refurbishment programme under Rocco Forte and Olga Polizzi’s team was to be celebrated on a luxury train ride from a mainline London Station to Kidderminster, steam hauled, champagne meal. It was on this train that many designers and leading contractors realised the disaster that was enveloping them was not unique to them but enveloped whole industries. What was intended as a celebration became a wake for an industry. Kidderminster, home to many carpet manufacturers was intended as a tour of the weaving sheds. At least one designer, aware that like the others, he was facing bankruptcy and losing his home and business, sat on Kidderminster station, head in hands and wept.

I began the distressing and deeply depressing process of dismantling the studio teams with redundancies. As we now had empty desks in the studio, I started advertising postgraduate programmes called ‘Studies in Practice’ that gave hands on site experience to designers wanting to start on their own. At first successful, even used by the local art school with their Masters degree postgraduate students filling desks, course buyers dried up as the market recession took serious hold. As the studio shrank and designers left with little prospects of new jobs the destruction caused by the Conservative government engulfed the country. I saw one estimate of 2 million small businesses disappearing. A neighbour had been made a director of an architectural practice employing over a hundred architects admitted to me that they were into single figure staff and were surviving by renting out space in their offices to other businesses. His wife had taken a lecturing post in a college, and I decided that rather than make any more redundancies I would do the same, accepting a post as Director of Visual Arts at Morley College in Waterloo.

Then my father, my hero, who had been unwell for some time, was admitted to a hospice with terminal cancer.

Not many men work their way up through the ranks twice. Not many in the late 1960’s wearing an air gunner brevet and medical symbols…

The bank repossessed our studios. They began to take assets to cover debts, including, because we were not a limited company, all our personal assets/savings, our pensions and insurances, cars and the marital home. Without being a limited company, they could take all our personal assets and they did. I used to drive home from the studio in the company van sometimes, and once I was parked around the corner from the house the bank was repossessing, enveloped in a white mist of stress. There was a knock on the window. A neighbour asked if I was OK as I had it seems been sat there for 2 hours. Morley became another task to rebuild whilst I rebuilt myself. My partners way of rebuilding involved getting too close to a rich client and we parted company and divorced. As the industry grew from recession, so we had found new offices and rebuilt income as clients returned to refurbishment programmes. I was forced to leave to company I had built, being told it had no value, and which my earnings from Morley supported whilst I again spent time helping to rebuild the practice. One major client never returned, Forte, bought and broken up by ‘venture Capitalists’ so-called, who were actually asset strippers, breaking up and destroying what had been Europe’s largest hotel chain.

The interest rate collapse happened I think in 1991/2, although much traumatised it is difficult to remember. I buried my dad in 1992, along with much of my achievements of the early years. Painting died too I thought, and I began to write, contributing to design magazines. By 1999, effectively out of the practice, I began to design and construct an online magazine on Hotel Design. At the age of 52, I was starting again…

Congratulations on your success. Commiserations on your slide down. I’m not an economist, but I watch politics closely, and am an amateur historian. I comment from NZ. It never ceases to amaze me the UK trope of ‘Fatcher’s Britin!” From what I can see Margaret Thatcher unleashed the latent potential of over-unionised and over bureaucratised Britain. Just take home ownership for one. Dying legacy industries like coal mining. Lack of vision to capitalise on the so called Common Market. Thatcher opened new opportunities for so many – the Apted film 7 Up is a great small scale case study of that. ‘the many nascent ambitious companies that her policies had allowed to grow energetically’ were crushed by fools. Well done on re-orientating yourself and finding new peace in photography, art, writing – and bell ringing

Typo under the carpet picture:

Met Police allowed a film company to blow the from off the shop next door to ours during filming.

For ‘from’ read ‘front’.

Glad I wasn’t there.

Corrected thanks