The representation of landscape has been a feature of art forever, but for the British their landscape has, since Turner and Constable fought their expressive battles in the hanging days at the Royal Academy, been an obsession. In the Towner collection is an early Patrick Hughes poster for ‘Art into Landscape’ in London’s Serpentine Gallery, and I have written here before how landscape is Art, so this exhibition focusses on a national passion.

In this show the scale of the photographic print becomes part of the thought provoking nature of the art. In some work it gives stature to the banal, allowing the banality to impose itself on the viewer. For others, as in the stunning works of John Davies, it reveals artistic quality and vision that in themselves justify seeing the exhibition, the scale making the works truly revelatory. The works of Davies allow him to become one of those in the show who raise the discipline into a genuine art form.

The Towner exhibition is advertised as focussing “on artists who have shaped our understanding of the British landscape and its relationship to identity, place and time”. It might be more accurate to describe them as ‘photographers with aspirations to be artists’ because in my view many of the pieces in this show fail to rise above the ordinary and, like much of today’s other expressive forms, fail to rise sufficiently above the mundane to be considered art.

Runcorn Bridges by John Davies

Runcorn Bridges by John Davies

In one conversation I had in the show a young artist posed questions about the inclusion of one landscape, (not that featured above!), being puzzled as to why its banality made it worth of inclusion as a gallery piece. In part its scale gave it a presence that its imagery did not sustain, and that points to one of the changes in technology of both taking and printing photographs that this show fails to acknowledge. The banality was contextualised by a photographer in the conversation, pointing out the presence of the photographer, his tripod and large plate camera making a sense of moment meaninglessly portentous, but also underlining thos technical changes.

For some the technicalities of equipment are important but this show largely reflects photography at the end of the last century rather than the myriad imagery created using the ubiquitous digital systems of the 21st century. The impact of new technology is changing the way we look at the world, not just through the changes in the camera but also in how the print can be realised. Whilst many photographic societies run their competitions limiting the size of prints to 10 x 8, the use of high quality digital prints means that for the photographer now, as much as it has been for the painter, the scale of the images changes the relationship the viewer has with the artefact, and the scale is no longer determinedby anything other than the photographers own creative desire.

Whilst it may have been true 20 years ago that large high quality prints needed large high quality negatives, which in turn meant large high quality camera gear, this is no longer the case. Now a small hand held digital single lens reflex camera such as Canon’s 5DS and its 55 megapixel sensor can have the sensitivity of a Hasselblad or a studio camera, giving the snapper the ability to take high quality images that will stand enlargement and printing at roadside billboard scale without losing quality. The rise of the giclée printer capable of printing at a resolution like that of a photographic studio negative means large scale prints can be made in a back bedroom, that a snapshot captuirng a moment can be as meaningful as an image that has taken days to plan and take.

Given that this collection was assembled largely between 1970 and 1995, before the technological impact of digital had struck home it is not surprising that what may have been epoch making in 1980 now seems mundane. That the collection that provides this work exists at all is down to the dedication of Barry Lane the Arts Council’s first photography officer. Since the turn of the century we have seen image making through digital means become democratised and proliferate.

A composer friend of mine used to bewail how contemporary classical music had sunk into a morass of muzak and pop culture. For the visual arts boundary between ‘high art’ and pop culture has become maintained only by an army of curators and art officialdom complete with their own mindset, like officials fromteh communist era ‘Artist Unions’ in the Soviet Union. It behoves us all to be open to see striking imagery in the everyday, as Hopper, Warhol and other painters did, and as many bloggers now do, accepting that for many the search for the dramatic can lead to manipulation and alteration into alternative realities. For that we need to develop our own critical faculties, and our ability to see clearly what is before us, for art is a language. It is evident that many have forgotten how to look, so used are they to having their vision fed, often cartoon style, from a screen.

Some of the works in this show fail to rise above this visual noise that surrounds us, raising questions about the curatorial team’s judgements and, as the young artist observed, questions about their inclusion. A gallery needs to show the exceptional in a way that makes us raise our own critical game. Fortunately, here there are enough examples here to satisfy this need.

John Davies is one of the individuals who raises the medium of photography into the realms of high art. Yes, his prints too are large here, but their scale enables the viewer to step into the image and enjoy the incredible richness of the landscapes he portrays. Almost allegorical in the storytelling he endows his photographs with, his view of Britain is all black and white, much as my memories of the North, albeit in my case the Northwest whereas his roots are in the Northeast. In his image of Reddish Vale, Stockport of 1988 he contrasts the youth and innocence of two young people in the foreground against the rape of the countryside by the building of a motorway in the background. The large scale of his vision and high viewpoint is allied to clear light and the subtleties of the black and white. His three large images dominate the entrance to the exhibition and for me are amongst the best in the show.

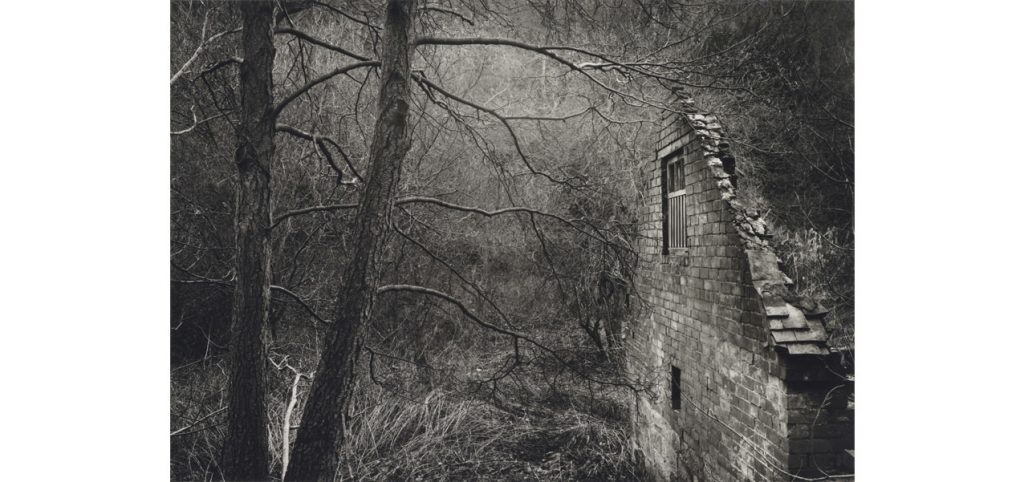

In contrast the work of Thomas Joshua Cooper opposite it is a contact print from a large format negative and its small size adds to the air of a secret revealed in this romantic image of a ruined cottage in Shropshire. Here the art is achieved by pulling an image that is almost representative of a collective memory of a time when fairies and mythological creatures stalked our land of Druids and witches.

Painters know well that a small painting is safe, you can embrace it within your arms whilst executing it, and as such is it non-threatening, contaioned within the artists being and psyche. Whereas change the scale beyond an arms embrace and the painting hugs you, you step into it, and it is far more an engulfing experience. Here photographers are realising the same thing. Whilst this enriches the experience in John Davies work, in others, such as the view by Melanie Friend of Eastbourne Pier, or her image of a blurred Lancaster over bathers on Eastbourne beach the virtuosity of the printer and the large scale does little to add value to what I see as an everyday snapshot. Maybe if the shot had been assembled with teh Lancaster in as sharp a focus as the bathers the finished image would have been much stronger, so easily achieved using digital means.

The Home Front by Melanie Friend

Others too use the large scale of the imagery to storng considered effect, and there is much here to reflect on the past of our country. Irish born artist Lucy Brennan-Shiel talked movingly of the importance of the images of Irelands landscape in the ‘Sectarian Murder ‘ series by Paulk Seawright and memory in the context of the photographs of watchtowers in Northern Ireland by Donovan Wylie. They form a part of a collective identity, much as I identify with the Northern landscapes of Davies, and are moving for what they imply and leave unsaid.

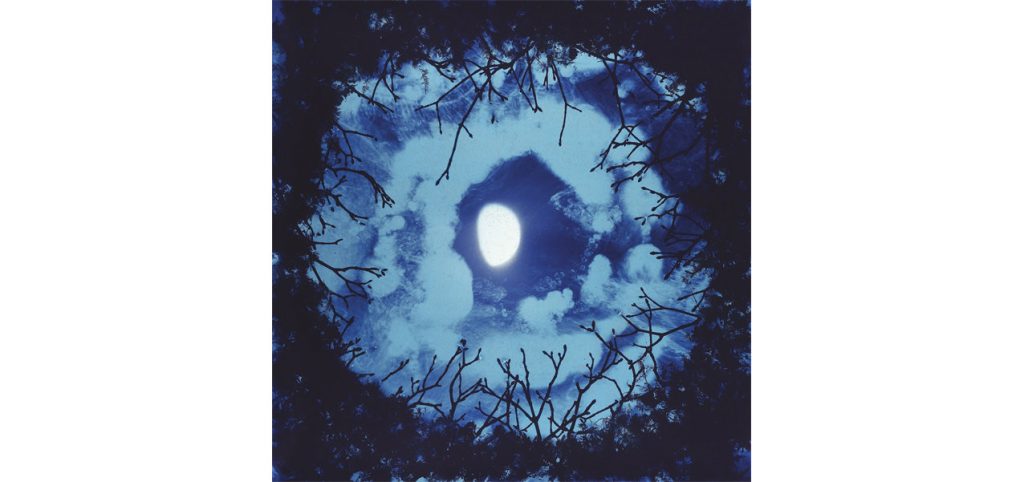

Near the end of the of the exhibition are two small images by Susan Derges that show processes not reliant on a camera at all. ‘Full Moon Rowan’ and ‘Luna’ of 2017 echo remembered student experiments with pin hole cameras and photographic papers, but with wonder and skill producing romantic images that are delightful as such but also technically very accomplished with the depth of field and quality of light.

Overall this is a stimulating show, questioning and full of vitality. Much is rooted in past technologies, but the questions raised are eternal in many respects, and have been developed and taken further by others and have fed into the collective mind that now takes a reputed 30 billion still images a year by digital media, many of them selfies and other trivia making up the visual noise of our time. Many of us take images every day, and this show will raise questions about their longevity and ability to change our world view if they remain confined to our own digital devices. That technology is changing the way we see our world in the way many of these photographers did over the last 50 years should never be doubted, even if now the impact is more from impressive film such as the current Blue Planet 2 series on the Beeb as well as teh still mage, areas where technology extends further the dramatic, almost accidental, images that can be formed by, for example, gluing a camera on the back of a dolphin.

The exhibition is in many ways much of its time and as such is backward looking. Its title is the title of one of John Davies’ books, and for me he is the star of the show, an artist whose work rewards long study. Even so there is much else here to enjoy, still more that is thought provoking and much to learn from in constructing images. That I have now been around it four times speaks volumes for the questions it raised for me, and will do for you if you make the effort to go. Do go, it is well worth your time, and it is free.

*************** ****************** ************ **************** ************* *****

The Towner is under threat as the local authority has decided to cut its grant in half, despite lavishing £44million on creating a cultural area around it. You can help the Towner survive the philistinism of Eastbourne Council by donating generously when visiting, or by becoming a supporter.

********************************** ********** ************************************

Receive this blog by email through the form in the right hand column

My art can be seen in the gallery section of this website

Recent Comments