For over eighteen months I have been working from images of my local sea defences, fascinated by the complexities of colour and texture generated by their decay. Sheet metal supposedly protecting the concrete structure that in turn protects a sewer treatment outfall, nowadays just a storm drain. We’re told. If you can believe anything a water company says about what it does to our rivers and beaches.

Over the headland on the Cuckmere estuary the sheet metal defends concreted structures put in years ago to protect the cable shed terminal, the cable making a link that enabled talks between London and Paris at the end of WW1. On both sides of the headland the metal sheets, driven in with steam powered pile drivers in the mid-twentieth century, are being destroyed by Atlantic swells weighted down with flints from the soft chalk cliffs.

The decaying metals collect the discarded detritus of our civilisation, a civilisation under pressure from global changes of all kinds – social, economic, and environmental. The defences carry the traces of the story of the decay into careless egocentricity driven by comfortable degrees of excess that shows in the discarded products washed ashore to hang from the groynes – rubber gloves, face masks by the score, old boots, plastic bottles, rubber ducks, pieces of timber, ropes, and large quantities of fishing gear. I am as concerned as any environmental campaigner about the pollution of our environment, but my focus has been to show through my art the decay here that is so symbolic of the decay across civil society at large.

BRotS #64 ‘Rust and Lichen’ A1 sheet size, image 27 x 16.5 inches. Paper primed with gesso. Splash Point seaward side of the structure, concrete revealed. £150

I have walked the headland in all weathers, watching the shipping, listening to the cries of seabirds, the rattle of branches, the sound of the surf, and all the time collecting images for processing. Sometimes this has produced stories about the art buried in full view in this wonderful landscape, a nature my eye has seen paralleling the work of other artists. In the rusting panels I see parallels with the work of artist Bridget Riley, so influential on my student days in the 1960’s, and my paintings are an homage to her in their naming as BRotS, but other artists are there too, their names a roll call of 20th century renown – Poons, Bernard Cohen, Bonnard, Hoyland etc..

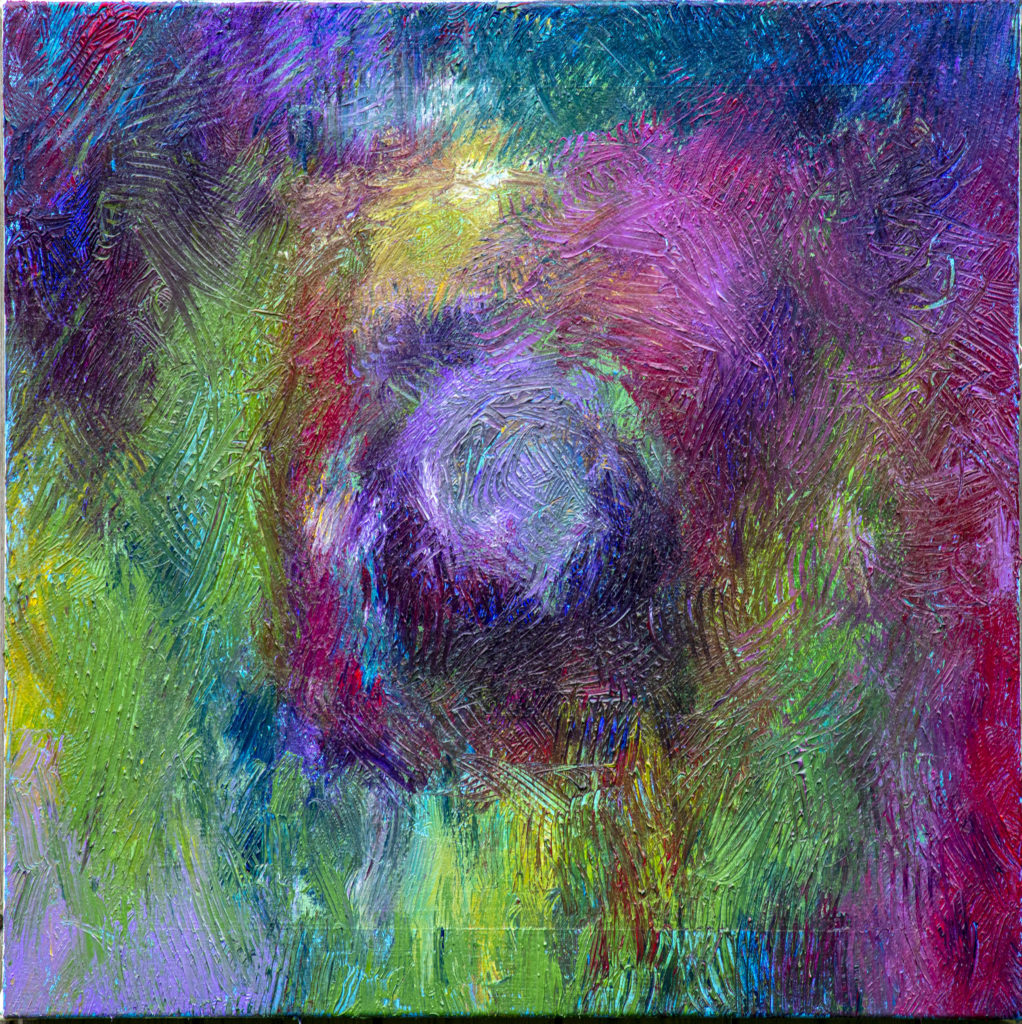

My own visual obsession with the colours has produced huge numbers of photographs and now an obsessive pursuit of both texture and colour over some 67 works on paper and 14 canvases, all completed in the last 18 months. I had been working with a series looking at how colour could break the square – a riposte to Albers formalism that I have had going on since 1977. The lack of a subject, just the colour alone, led to a series of images of the garden, but the square began to disappear with the ‘Peg ‘ series and find its apogee with the Brexit Daisy (now in a private collection) which I suppose also marked the point at which my paintings moved on from a passive reflection of survival after the trauma of cancer, and a shift to focus outwards rather than inwards.

From the start I settled on a standard paper size to work on for simplicity, transferring all the focus onto the methodology. I had been working portrait orientation on A1 and for the first few this continued, with the medium then being oil pastel, but the nature of the subject drove me into landscape format and a visit to my local art suppliers provided a surprise new painting tool which generated formidable textures in acrylic paints and rapidly led to a variation on the textures I had generated with the brush in the flower paintings.

I continue the exploration, flirting with imagery in works such as ‘Chocolate Teapot’, trying to tread a line between abstraction and representation. Every so often the exploration demands a canvas result, the mythmaking and ritual. Now the question I ask myself is have I become a prisoner of the exploration, a prisoner of what is becoming habitual. Can I go on trusting in rust or is my mind rusting? Yet every time I start thinking, seeing takes over. Art is a visual skill after all, and new photographs reveal new details, new colour to explore and the fun takes over and the pursuit of this obsession continues. The latest exploration has involved some complex atonal research as the underpainting to see how it alters the approach to the end game. The answer is it does, but not by much. Much more important is working out ways to remove the white of the primer from the equation. Much as Cézanne is supposed to have been reluctant to cover the last piece of primer because it changed the colour relationships he had built his paintings on, so I also find the white of priming an annoyance when working with colour.

The latest works separated out what had become an irritant in the imagery, that of the bolts holding on the metal panels. On a set of 2-foot square canvases I experimented with different variations on the underpainting and how this affected the final painting. The formalised underpainting as shown at the top of this blog, was unnecessary, although removing the white with colour was good, but removing the bolts as a consideration in future pieces has been a good move. They were disturbing my balance in treading this line between representation and abstraction, disturbing the abstraction the stripes of metal plates represented.

So, I am still trusting my instincts, the colour is still changing with the rusting/time/tide. I recently had to turn down a solo show because of an upcoming operation which I hope with lead to more winter walks to the Cuckmere when ‘surfs up’. It will be my sixth major operation in as many years. The 67 works are down to some 55 now after sales during ArtWave so maybe I will use my immobility to put together a book of Trusting the Rusting. You can be sure if I do you can read about it here first

or on my twitter feed at Patrick A. Goff (@patricktheart) / Twitter

or, if you follow the studio page, maybe on Facebook

Recent Comments